When Did the Legalization of Abortion Become Popular?

Sometime between 2018 and 2021 in the U.S., for elective cases.

Introduction

In the previous article on U.S. public opinion about abortion1 in the 1960s, we saw that attitudes toward the legalization of abortion were divided into three tiers depending on the circumstances leading to abortion.

Over 70% of Americans supported the continued legalization of abortion when it was necessary to preserve the health of the mother against serious injury. However, over 70% of Americans rejected the legalization of abortion in elective cases such as a couple not having enough money, a woman being unmarried, or a couple simply not wanting more children. In the middle, a simple majority of Americans supported the legalization of abortion when the child was likely to be severely deformed and when the pregnancy was a result of rape.

Public opinion about abortion in the United States has changed since the 1960s. It did so during two discrete periods of time. The first occurred during the late 1960s and early 1970s. The second occurred from the turn of the millennium to the present, but only in a subset of the population.

Survey Quality

In my previous article on public opinion during the 1960s, I lamented the lack of data on the subject. After the 1960s, we have the opposite problem. From the 1970s on, there have been many polls about public opinion on abortion in the United States. For a comprehensive summary, see the review by Bowman and Goldstein (2021).

Most of these polls aren’t worth much. The fundamental problem is that survey responses to questions about abortion — like a lot of other controversial issues — are very sensitive to how the questions are framed and worded. Indeed, as we shall see, results are sensitive even to the order in which questions are asked. Therefore, results vary considerably from one bad poll to the next.

For a survey on public opinion about abortion to be useful for analysis, it needs a few characteristics:

The survey must be repeated over an extended period of time using the same questions.

The first time a survey is administered, it only establishes a baseline. It tells us what results we get from the particular wording used in the survey, which is not comparable to other surveys because even slightly different wording can result in large differences.

Questions must be specific.

This dismisses another swath of bad polling. For instance, asking people whether they consider themselves “pro-choice” or “pro-life” is pointless because respondents have wildly different ideas of what it means to be “pro-choice” or “pro-life.”

Another genre of non-specific questions involves questions that presume a linear scale. These are of the “a lot more,” “a little more,” “a little less,” or “a lot less” form. It is dumb to ask respondents “how much” abortion restriction they support because people have strong opinions on the validity of abortion based on the specific circumstances.

For instance, if the modal American respondent of the 1960s was living in the modal American state of the 1960s, that respondent would want restrictions of abortion loosened or lifted in the cases of severe fetal deformity and pregnancy from rape simultaneously with wanting restrictions maintained or even strengthed in elective cases.2

Samples must be representative.

Since public opinion analysis is concerned with what proportion of a population gives a specific response to a question, it is important for the sample to accurately reflect the population. It is well-known how to do this. You need a sampling frame that enumerates the target population (and only the target population). Then, you need to randomly select from that frame with a known probability of selection for each respondent.

While this is a solved problem in theory, actually doing it is another thing. In practice, it is very expensive and will become even more expensive as survey response rates continue to plummet.

Because of low response rates, care must be taken to adjust results for response bias. Typically, this involves weighting adjustments to make estimates match known population totals for key variables. However, this isn’t always done.3

General Social Survey

The only data source for analyzing trends in public opinion about abortion in the United States that meets all these criteria is the General Social Survey (GSS), which is run by the National Opinion Research Center (NORC).4 NORC has run the GSS since 1972, and the GSS includes questions about abortion attitudes in its core module. Therefore, the GSS has repeatedly asked the same questions about abortion attitudes every other year or so since 1972. In fact, NORC actually did a survey with the same questions about abortion attitudes in 1965, so we have data going back to before the GSS started.

The GSS is by no means perfect. For instance, its core module only asks questions about the legalization of abortion by circumstance. Another large factor in public opinion on abortion is the timing of the abortion (e.g., first versus second versus third trimester). Such questions have only been rarely asked on the GSS.

Another issue is that the GSS core only asks about abortion policy. People have dramatically diverse views about abortion outside of the public policy context, e.g., what they think about abortion from a moral standpoint, whether or not they would themselves seek an abortion, whether they would help others procure an abortion, etc.

The biggest issue with the GSS for this analysis, however, is that it doesn’t cover most of the time period when the first change in public opinion about abortion occurred. The 1965 survey by NORC gives us a snapshot of public opinion before this change, and the GSS catches the tail end of this change, but that is it.

Another issue is that NORC changed from in-person interviews to online questionnaires for the 2021 GSS and then to a mixture of in-person interviews and online questionnaires for the 2022 GSS. NORC advises:

Changes in opinions, attitudes, and behaviors observed in 2021 and 2022 relative to historical trends may be due to actual change in concept over time and/or may have resulted from methodological changes made to the survey methodology during the COVID-19 global pandemic. Research and interpretation done using the 2021 and 2022 GSS data should take extra care to ensure the analysis reflects actual changes in public opinion and is not unduly influenced by the change in data collection methods. For more information on the 2021 and 2022 GSS methodology and its implications, please visit https://gss.norc.org/Get-The-Data.

In this article, I do not investigate whether the methodological changes affected the abortion attitudes results from the 2021 GSS and the 2022 GSS. It isn’t critical to this article’s analysis, but it is good to be aware of.

Gallup

This analysis uses Gallup polling to supplement the GSS. Gallup’s polling is not as good as the GSS for various reasons.5 However, Gallup has asked more questions about abortion attitudes repeatedly than the GSS.

In addition, Gallup polling about abortion took place during the critical 1968-1975 time period. The results of these polls, however, are not available on Gallup’s public website. Sociologist Judith Blake commissioned the 1968-1975 polls, and it appears the only publicly available results from these polls are whatever she happened to publish in academic journals.

National Fertility Survey

The National Fertility Survey (NFS) was administered in 1965, 1970, and 1975, and it included questions about attitudes toward abortion. Unlike the GSS and Gallup polls, the NFS target population comprised women who had ever been married rather than all adult Americans.

In fact, the 1975 NFS target population is even stranger. The survey tried to create a 1975 sample that revisited women from its 1970 sample. Thus, the 1975 target population became continuously married White women whose duration of marriage was less than 25 years, who married at age 25 years or less, and whose husbands had only been married once.

Therefore, the 1975 NFS does not reflect a cross-section of American ever-married women, and we should view any results from it with skepticism.

1968 to 1973

Gallup/Blake

The Gallup polls from 1962 to 1977 that were done at the request of Judith Blake (henceforth “Gallup/Blake” polling)6 started off asking three questions:

Do you think abortion operations should or should not be legal in the following cases:

a. Where the health of the mother is in danger?

b. Where the child may be born deformed?

c. Where the family does not have enough money to support another child?

From 1968 on, a fourth question was added.

d. Where the parents simply have all the children they want although there would be no major health or financial problems involved in having another child?

Blake’s 1971 paper only reported on the opinions of White people. (See previous discussion about this.) However, her 1977 paper expanded results to include all Americans, and it is unlikely the racial exclusion in the 1971 paper changed the results substantially.

The 1971 paper only reported disapproval rates, whereas the 1977 paper reported both disapproval and approval. However, the 1977 paper only reported on the responses to the question about when “parents simply have all the children they want.”

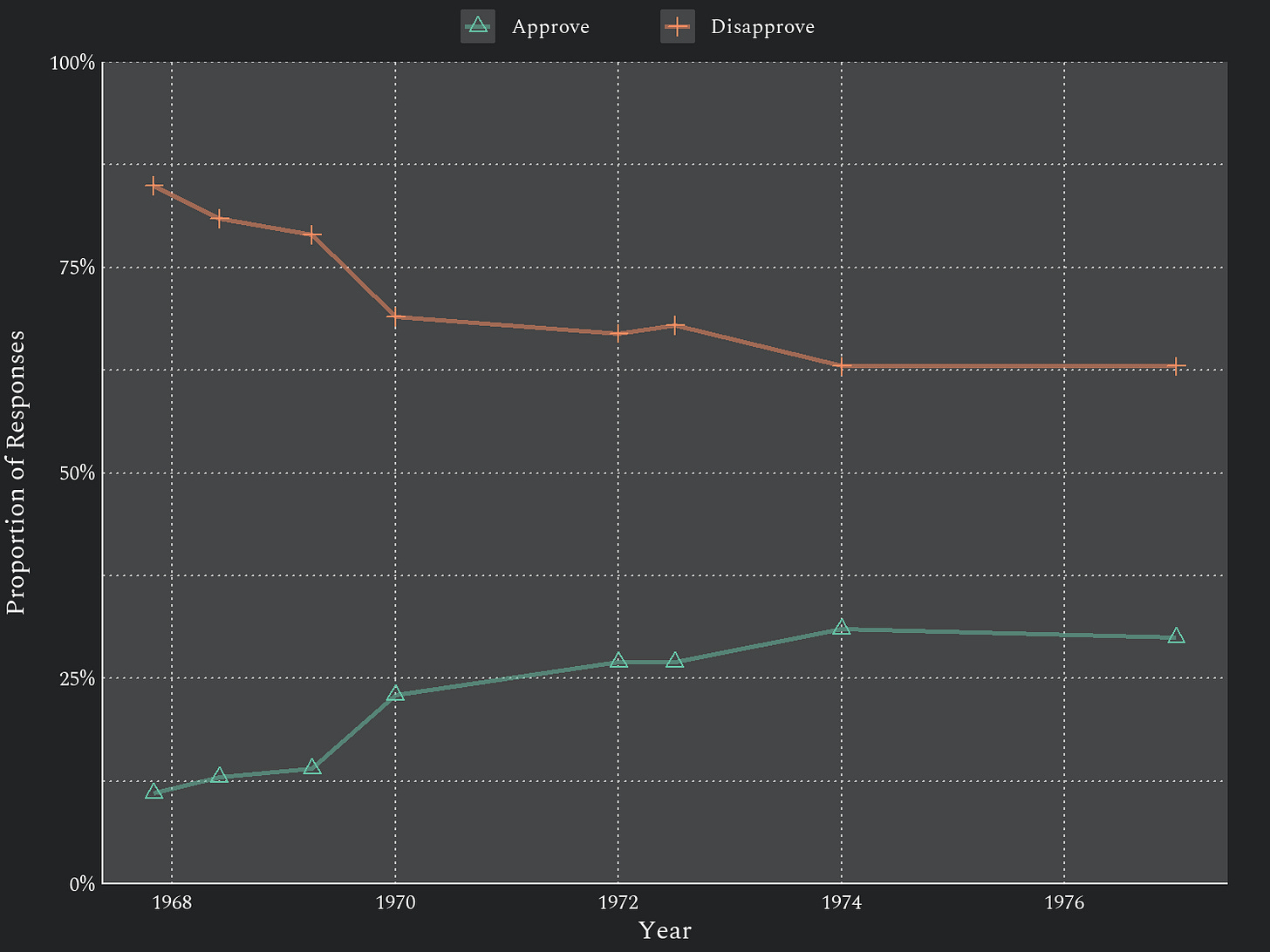

There appears to be a downward trend in disapproval from 1968 on for the “no more children” scenario. However, the question was first asked in 1968, so we can’t be sure if this downward trend started earlier. There might be a smaller downward trend in the disapproval rate for the other questions between 1965 and 1968.

Therefore, the change in public opinion toward elective abortion started at least by 1968 and perhaps as early as 1965.

The change in public opinion appears to level off by 1974. In 1974, 31% of Americans approved of the legalization of abortion in the “no more children” case, and in 1977, 30% did.

Even after this change in public opinion, in 1974, 63% of Americans disapproved of the legalization of abortion when parents simply had all the children they wanted, and in 1977, 63% did again. When the question was first asked in 1968, the disapproval rate was 85%.

Therefore, according to Gallup/Blake polling, there was a change of about 22 percentage points in American attitudes toward elective abortion during the 1968-1974 time frame before leveling off. Even with this change, the legalization viewpoint was the minority position.

National Fertility Survey

The NFS confirms the Gallup/Blake polling. For all six questions7 about abortion attitudes asked in the three iterations of the NFS, there was a trend of increasing approval and decreasing disapproval.

Since the 1975 NFS is not a representative cross-sectional sample, its results should not be taken as reflecting the proportion of attitudes in the population. That being said, it is directionally consistent with the Blake/Gallup polling as approval of abortion in elective cases remains a minority position.

The timing of the NFS in 1965 and 1975 means that these results do not narrow the time frame for the change in public opinion. We already knew from the Blake/Gallup polling that it started as early as 1965, had started no later than 1968, and ended by 1974.

1965 NORC Survey and the General Social Survey

If we take the results of the survey done by NORC in 1965 together with the GSS during the 1970s, the combined results confirm there was a trend of increasing approval of legalized abortion in response to all six questions.8

Again, these results do not help identify the beginning of the trend. We already knew it might have been as early as 1965.

The GSS shows a distinct leveling off of the trend by 1973, which is only slightly earlier than the 1974 inflection point in the Blake/Gallup results.

Approval of elective abortion appears to plateau at a much higher rate in the GSS results than in the Blake/Gallup results. In 1973, a peak of 47% of Americans approved of legalized abortion in the “married and does not want any more children” case on the GSS, which is the closest to the “parents simply have all the children they want” case in the Blake/Gallup results where approval peaked at 31% in 1974.

The 1965 NORC survey found that 16% approved of the legalization of abortion in the “parents simply have all the children they want” case. The 16% to 47% change in approval in the NORC/GSS results would represent a 31 percentage point change, larger than the 22 percentage point change found in the Blake/Gallup polling.

Blake (1977) explains the difference between the NORC/GSS and the Blake/Gallup results as due to differences in wording and question order. The Blake/Gallup question explicitly stated that there were “no major health or financial problems involved in having another child,” and it was asked after three questions about health and financial issues.

In contrast, the “married and does not want any more children” question in the NORC/GSS surveys was the second question, after only the “serious defect in the baby” question and before questions about health and financial issues.

Thus, respondents to NORC/GSS surveys might think of health or financial issues when answering the “married and does not want any more children” question, but respondents to the Blake/Gallup “no more children” question almost certainly did not think of these extenuating circumstances.

The NORC/GSS results, therefore, overestimate support for the legalization of elective abortion somewhat. Exactly how much, we cannot know.

Like the other sources, support for the legalization of elective abortion plateaus in the GSS results as minority viewpoints, except for the low-income case, which plateaus at just above 50%.

Summary

There was a broad increase in public approval of the legalization of abortion that began at least by 1968 — perhaps as early as 1965 — and ended in 1973 or 1974. For elective abortion, this change was somewhere around a 22 to 31 percentage point increase.

Even with this trend, the viewpoints that were in the majority remained the same. A majority of Americans approved of the (continued) legalization of abortion in cases of serious health risks to the mother, high likelihood of severe fetal deformity, and pregnancy resulting from rape. A majority of Americans disapproved of the legalization when a woman was unmarried or a couple simply did not want another child.9

Despite not resulting in a change in which viewpoints were in the majority, the 1968-1973 change made abortion politics much more contentious. In the 1960s, the legalization of abortion in elective cases was a political non-starter. In the 1970s, a sizable minority supported the legalization of elective abortion.

Women’s Opinions

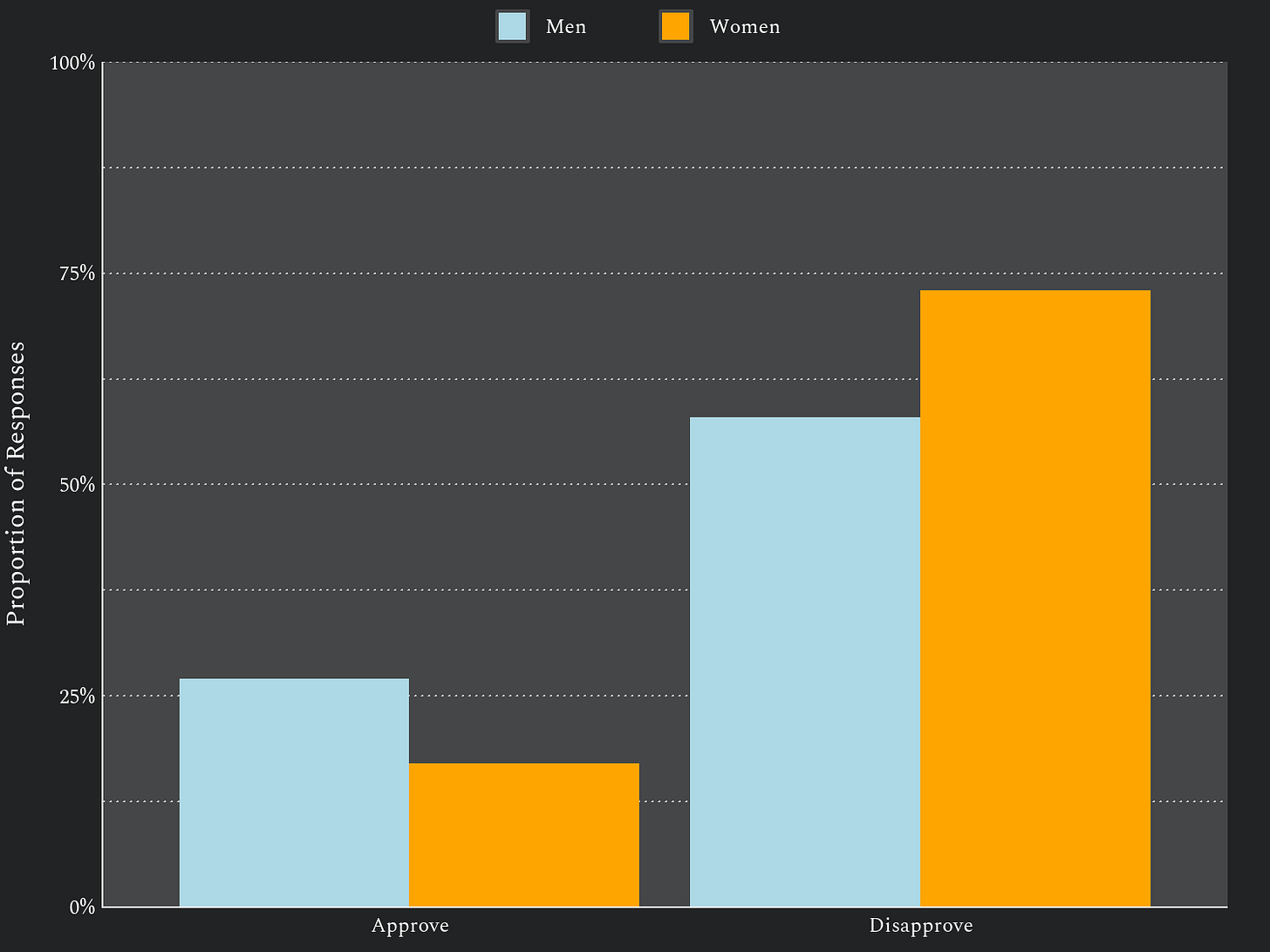

The 1970s continued the phenomenon from the 1960s that women were more opposed to the removal of abortion restrictions than men in the United States. The overall difference in both decades was small, but it could be more substantial in certain subdomains or on certain questions.

In the Gallup survey of January 1973, more women than men believed that abortion should be allowable only if the pregnancy was at 3 months or less. Indeed, more women volunteered that abortion should never be performed than selected the response option that there should be no legal restriction on the timing of abortion.

This result was confirmed by the Gallup survey of April 1975, which found that more women (73%) than men (58%) disapproved of a law that would permit women to have an abortion even if they were more than three months pregnant.

When asked “when human life begins” in the January 1973 and April 1975 surveys, more women than men answered “at conception,” whereas more men than women answered “at birth.” (Overall, pluralities of both women and men replied “at conception.”)

Roe v. Wade and Doe v. Bolton

Public opinion was overruled in the 1973 U.S. Supreme Court opinions Roe v. Wade and Doe v. Bolton, which removed the issue of abortion from the normal political process. Roe v. Wade overturned all laws prohibiting abortion for any reason up until fetal viability, which was stipulated to occur at some point during the seventh month (24 to 28 weeks) of pregnancy.

Roe and Doe occurred at a local maximum of public approval of elective abortion cases and right when the change in public opinion plateaued. Asking respondents about the circumstances under which they approved of abortion was suddenly a lot less relevant. Roe had legalized abortion-on-demand, i.e., abortion whenever it was requested, without any criteria about the circumstances that led to the request.

The GSS added a question asking specifically about abortion-on-demand in its 1977 iteration, a few years after Roe v. Wade. The question reads:

Please tell me whether or not you think it should be possible for a pregnant woman to obtain a legal abortion if the woman wants it for any reason?

The 1977 GSS found that the legalization of abortion-on-demand had only 37% approval.

Judging by how flat the support for legalized abortion in the elective cases was between 1973 and 1977, it is unlikely that support for abortion-on-demand was much higher in 1973 than in 1977. Therefore, when the Roe v. Wade opinion was issued, only about 37% of Americans approved its policy implications. This 37% estimate is closer to the 31% approval Blake/Gallup found for the “no more children” case than other GSS results from the same time frame.

In contrast, about 61% of Americans rejected the legalization of abortion-on-demand.

Public opinion was actually worse for Roe v. Wade’s policy implications than this 61%-to-37% split because, as we have seen, most Americans rejected the legalization of abortion after the first trimester, as well, and Roe legalized abortion-on-demand until the early third trimester.

1977 to 2000

We see in Figure 7 that, in the 1977 GSS, when the abortion-on-demand question was first asked, there was a clear ordering of support for legalized abortion in elective cases. Abortion in the case of low income had the highest approval, followed by the case of unmarried women, followed by married couples who do not want more children, and finally, abortion-on-demand.

From 1977 into the mid-1990s, approval of all of the elective abortion cases consolidated in such a way that the approval rate for any one case became similar to the approval rate for any other.

Approval of elective abortion reached a local maximum in the 1994 GSS in the high 40 percents. After this, there was a decline in approval of elective abortion to a nadir of around 37% in the year 2000.

2000 to 2022

According to GSS results, support for the legalization of elective abortion climbed steadily throughout the Twenty-first Century. It finally became a majority viewpoint sometime between 2018 and 2021.10

Overall, approval for the legalization of abortion-on-demand went from 36% in 2000 to 55% in 2022. This 19 percentage point change is smaller in magnitude than the 22 to 31 percentage point change that occurred in the 1968-1973 period, and it occurred over a longer period of time.

However, the 2000-2022 change has more implications. Support for the legalization of elective abortion went from a minority viewpoint to a majority viewpoint. Furthermore, the 2000-2022 change has been very partisan.

Partisanship

In the mid-1970s, Republican-leaners were slightly more likely to approve of the legalization of elective abortion than Democratic-leaners,11 but the difference was small. From the late 1970s through the 1980s, there was little to no partisan difference in attitudes toward elective abortion.

Starting in the 1990s, Democrats and Republicans separated in a process of partisan sorting, with Democrats approving elective abortion at a higher rate than Republicans. However, throughout the 1990s there was a decline in approval of elective abortion in both parties until the nadir of approval of elective abortion in 2000.

From the year 2000 on, Republicans have approved of elective abortion at more or less the same rate. However, approval of elective abortion by Democrats has skyrocketed during this same time period.

In 2000, about 29.8% of Republicans approved of the legalization of abortion-on-demand, and in 2022, it was about 29.4%. However, Democrats went from 41.3% approval of the legalization of abortion-on-demand in 2000 to a whopping 82.2% in 2022 — a difference of about 41 percentage points!12

In terms of magnitude, the 41 percentage point change among Democrats is substantially larger than the 22 to 31 percentage point change among all Americans from 1968 to 1973.

The effect on the Democratic Party cannot be understated. A position that was mildly unpopular among Democrats in 2000 has become extremely popular among Democrats in 2022.

Women’s Opinions

After I learned from reading Judith Blake that women in the 1960s and 1970s disapproved of legalized abortion at a higher rate than men, I asked myself, when did this change?

It turns out it didn’t. Women have never approved of legalized elective abortion at a higher rate than men.

The difference in approval of legalized abortion in the four elective cases between men and women is small, but generally, men approve of abortion at a higher rate than women.

There have been 33 iterations of the GSS that asked about abortion attitudes. The first 5 iterations asked 3 questions about elective abortion, and the remaining 28 iterations asked 4 questions. This means there are 127 comparisons in Figure 10.

In these 127 comparisons, the estimate of approval for legalized elective abortion was higher for men in 104 cases (82%) and women in 23 cases (18%).

However, I fit simple logistic regression models with abortion attitude as the response variable and sex as the explanatory variable for each of these cases. Even before adjusting for multiple comparisons, no comparison with a higher estimate for women than men was statistically significant with α = 0.05. Therefore, these cases are likely due to statistical noise.

Approval of legalized elective abortion has either been greater among men than among women or has been the same (within the statistical precision of the survey).

Gestational Age

How about the result found by Judith Blake that most Americans disapprove of laws permitting abortion after the first trimester?

This also hasn’t changed.

Gallup polling from 1996 to 2023 has found that a majority of Americans reply that “abortion should generally be legal” during the first trimester, and majorities reply that “abortion should be generally illegal” during the second and the third trimester. The gap has narrowed since 2011, but which response is in the majority has not changed.

Popularity of Roe v. Wade

At the same time that most Americans have not supported the actual policy implications of Roe v. Wade, most Americans have opposed repealing Roe v. Wade.

From 1989 to 2022, a majority of Americans have indicated on Gallup polling that they would not like to see Roe v. Wade overturned.

Discussion

The 1968-1973 increase in approval of the legalization of abortion follows an injection of funding for abortion advocacy by billionaire benefactors. In 1966, John D. Rockefeller III began funding Robert Hall’s Association for the Study of Abortion and Roy Lucas’ James Madison Institute, which lobbied for the legalization of abortion. During this time period, wealthy men such as Warren Buffet and Richard Mellon Scaife funded litigation efforts to legalize abortion. (Forsythe 2013, pp. 59-60)

The 1968-1973 increase in approval for legalized abortion thus may have been the consequence of a well-funded advocacy effort without an organized counteracting lobby. This hypothesis is consistent with the change in public opinion leveling off in 1973, when Roe and Doe provoked the creation of organized anti-abortion lobbying at a national level.

The effect of partisan sorting on public opinion about legalized abortion in the United States cannot be understated. The changes in public opinion after the year 2000 are extremely partisan.

During the 1990s, Democrats had higher approval rates for the legalization of elective abortion than Republicans for the first time. However, during partisan sorting in the 1990s, support for legalized abortion actually declined.

In the Twenty-first Century, it has been trendy for Democrats to accuse Republicans of “asymmetric polarization” and of becoming more “extreme.” It is clear that on abortion, the opposite is the case. Republicans are basically where they were after the partisan sorting in the year 2000, whereas Democrats have undergone a massive 41 percentage point change. Republicans in 2022 are closer to where Democrats in 2000 were on abortion than are Democrats in 2025.

The partisan sorting was likely a prerequisite for this. Grouping most of the abortion advocacy into one party created an echo chamber that allowed viewpoints to snowball. There has been a bias in mass media and academia since at least the 1970s in favor of abortion advocacy. Mainstream media and academia today are heavily aligned with the Democratic Party. The partisan sorting allowed a confluence between these phenomena.

Women Have Never Approved of Abortion Legalization at a Higher Rate than Men

When I went looking for the year that women started to support legalized elective abortion at a higher rate than men, I was genuinely surprised to find this never occurred. I was likely influenced by the mainstream media narrative that constantly repeats the refrain that “women want abortion.”

This result is even more surprising considering the gender polarization going on in the United States — in which women are more likely to vote Democratic and men more likely to vote Republican — and the polarization between parties on the issue of abortion. There is likely something going on here that is worth investigating in a subsequent article.

Democrats’ belief in their own false narrative likely contributed to one failure of the Harris-Walz campaign for U.S. President in 2024. The Harris-Walz campaign was criticized for not saying anything concrete about many issues. However, this criticism did not apply to abortion, as the Harris-Walz ticket prominently emphasized the issue of abortion throughout the campaign.

However, the Harris-Walz campaign performed worse among women voters in the 2024 election than the Biden-Harris campaign did in the 2020 election.

I suspect there is a minority of women for whom opposition to restrictions on abortion is their one main issue. As a result of this being their issue, this subset of women is quite loud and vociferous about their views on abortion. Furthermore, because of the partisan sorting, this subset of women is now virtually all in Democratic-leaning spaces.

Thus, in Democratic-leaning spaces, this subset of women is prominent and interpreted as representing “women” writ large. However, given how extensive party polarization is on abortion, most of the voters — women or men — who would vote for a Democrat because of abortion have already been Democratic-leaning voters for years now.13 Therefore, running on abortion is unlikely to get you additional votes in high-turnout elections like for the U.S. President.

Looking back at the first paragraph in this Discussion section, there are a lot of male names who funded the abortion lobby and who led the organizations lobbying for abortion in the 1960s and 1970s. Roe v. Wade and Doe v. Bolton — the great win of the abortion lobby — were the opinions of seven men. Maybe I shouldn’t have been so surprised that legalized abortion has been more popular among men than women.

Repudiation of Gallup’s “Circumstances” Question

I partially retract an analysis from an earlier article in which I wrote:

Democrats as a party have been captured by what is a minority viewpoint among all Americans. Approximately 60% of Democrats think that abortion should be legal in all circumstances, compared with only 34% of Americans who think that abortion should be legal in all circumstances.

This is based on a Gallup polling question about whether abortion should be “legal in all circumstances,” “legal in some circumstances,” or “illegal in all circumstances.”

I now think it was a mistake for me to even care about the results of this question. As I discussed in the “Survey Quality” section of this article, these kinds of questions are too non-specific to shed much light on public opinion.

I think the 55%-42% split in favor of legalized abortion-on-demand in the 2022 GSS results is more relevant because it is based on a specific policy question. Indeed, this 55%-42% split is closer to the voting results on several state abortion referenda, such as in Ohio and Florida.

I suspect a lot of the people who pick the “some circumstances” option in Gallup polling are thinking of limiting abortion to the first trimester of pregnancy since, as we have seen, majorities in the same Gallup polling think that abortion in the second or third trimesters should generally be illegal.

Of course, the abortion referenda that recreate Roe and Doe legalize abortion-on-demand throughout the second trimester and into the early third trimester. It may be the case that some voters simply value the legality of first-trimester abortions over the illegality of second-trimester and third-trimester abortions.

Indeed, the state of Nebraska defeated its referendum recreating Roe and Doe and passed a counter-referendum in its 2024 election. Nebraska currently has generally legal abortion in the first trimester, which may have undercut support for the referendum to recreate Roe and Doe.

This being said, my main thesis from the earlier article is confirmed by the analysis of this article: Abortion is a get-out-the-vote issue for Democrats, not an issue Democrats can use to win persuadable voters, because party sorting by views on abortion is already nearly complete.14

The Policies of Roe v. Wade Never Had Majority Support

A majority of Americans finally supported the legalization of abortion-on-demand shortly before the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision of 2022 overturned Roe v. Wade, which is what had legalized abortion-on-demand (in 47 states) in the first place.

Furthermore, during the entirety of the time between Roe and Dobbs, a majority of Americans opposed the legalization of abortion in the second trimester and the third trimester, and Roe legalized abortion-on-demand in the second trimester and part of the third trimester.

Thus, Roe and Doe were a political coup d'état without which the abortion lobby could not have been so successful. The legalization of abortion-on-demand was supported by only 37% of Americans in 1977 and, again, by only 37% of Americans in 2000. In 2022, with abortion policy finally becoming a subject of legislation again, support had risen to 55% of Americans.

The strategy that Judith Blake outlined and that the abortion lobby took in the 1970s was not to make public policy match public opinion on abortion, but to make public opinion match public policy — after changing public policy by way of judicial activism. Thus, politics has been a tool of the abortion lobby to change public opinion.

This has worked. The referenda enshrining abortion in the various state constitutions have been retreads of Roe and Doe, sometimes using the exact same wording. Unlike Roe and Doe, which were opinions of seven unelected judges, these referenda have passed by popular vote. Roe and Doe gave 45 years of cover to the abortion lobby to make this work.

If Planned Parenthood v. Casey in 1992 had overturned Roe and Doe instead of reaffirming their core holdings, the political landscape would have been very different. Casey occurred right before a downward trend in approval of abortion-on-demand that only started to reverse in 2000.

It is curious that a majority of Americans simultaneously opposed Roe’s policies and opposed its overturning. I speculated in the past that this was in part due to many Americans not understanding what policies Roe actually created.

I have seen numerous people, including book authors and journalists, wrongly state that Roe legalized abortion-on-demand in just the first trimester when it actually legalized abortion-on-demand throughout the first and second trimesters and into the beginning of the third trimester. Indeed, sometimes, polling questions themselves misrepresent Roe in this way. (Bowman and Goldstein, 2021)

Some of this false belief might be due to Roe legalizing abortion-on-demand until “viability.” Some people do not know when viability occurs.15

Another major reason for the seemingly contradictory simultaneous opposition to Roe’s policies and to overturning Roe is that some people prefer to maintain the status quo. I have seen numerous people assert that Roe and Doe were “long-standing” or “established” and so should continue.

Gallup didn’t start asking about overturning Roe until 1989, more than 16 years after Roe, by which time it was presumably “established.” In 1989, 57% of Americans were against the legalization of abortion-on-demand, but 58% of Americans were also against overturning Roe.

Regardless of what accounts for it, the difference between support for legalized abortion-on-demand and support for overturning Roe has been critical in the abortion lobby’s program of changing public opinion through policy.

Conclusion

In the 1960s, a majority of Americans approved of the legalization of abortion when it was necessary to preserve the health of the mother, when a pregnancy was the result of rape, or when the child was likely to be severely deformed. At the same time, most Americans rejected the legalization of abortion in elective cases, such as when a woman was unmarried or when a couple didn’t want another child.

Starting sometime between 1965 and 1968, public opinion began to change toward greater approval of legalized abortion. By 1973, this trend plateaued, and approval remained at the same levels in subsequent years before dropping again. During this plateau, a greater proportion of Americans approved of the legalization of elective abortion than during the 1960s, but this remained a minority viewpoint.

In the 1990s, there began to be a difference in viewpoints on the legalization of elective abortion based on political party affiliation, with Democratic-leaning voters approving of elective abortion legalization at a higher rate than Republican-leaning voters. Still, approval of elective abortion legalization declined throughout the 1990s, reaching a nadir in the year 2000.

From the year 2000 on, the rate of approval of the legalization of elective abortion among those who tend to vote Republican has remained more or less the same. At the same time, the rate at which Democratic-leaning voters approve of the legalization of elective abortion has skyrocketed. Approval of legalized abortion-on-demand was a minority position among Democrats in 2000. By 2022, it was the view of over 80% of Democrats.

Because of this dramatic change in viewpoints among those who tend to vote Democrat, and because of the lack of a change in viewpoints among those who tend to vote Republican, support for the legalization of abortion-on-demand went from a minority viewpoint to a majority viewpoint sometime between 2018 and 2021, shortly before Dobbs overturned Roe v. Wade.

References

Blake, J. (1971). Abortion and Public Opinion: The 1960-1970 Decade. Science, 171(3971), 540–549. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.171.3971.540

Blake, J. (1977). The Supreme Court’s Abortion Decisions and Public Opinion in the United States. Population and Development Review, 3(1/2), 45–62. https://doi.org/10.2307/1971759

Bowman, K., & Goldstein, S. (2021). Attitudes about Abortion: A Comprehensive Review of Polls from the 1970s to Today. https://www.aei.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Attitudes-About-Abortion.pdf?x91208

Evers, M., & McGee, J. (1980). The trend and pattern in attitudes toward abortion in the United States, 1965–1977. Social Indicators Research, 7(1), 251–267. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00305601

Forsythe, C. D. (2013). Abuse of discretion: The inside story of Roe v. Wade. Encounter Books.

Unless otherwise noted, in this article the word “abortion” is used to mean induced abortion of pregnancy.

Technically, the word “abortion” is a generic term. Any process that is aborted before it comes to completion can, in theory, be labeled “abortion.” However, because of its association with abortion of pregnancy and the emotional weight of such occurrence, the word “abortion” is usually used to mean abortion of pregnancy.

Furthermore, even if we just consider “abortion” to mean abortion of pregnancy, there is ambiguity because in the medical literature, the word “abortion” is used to mean two different things: spontaneous abortion, which is commonly called “miscarriage” in the vernacular, occurs when a pregnancy terminates without anyone’s intervention; induced abortion occurs when a pregnancy is terminated on purpose. When “abortion” is used in the vernacular, it is commonly used to mean induced abortion.

This ambiguity can lead to misinterpretation. For instance, if a study were to report on abortions in a given population, it could include both spontaneous and induced abortions if it were using the medical literature definition, but it could exclude what are commonly called “miscarriages” if it were using the common definition.

The vagueness of questions has actually been exploited in the past. For instance, you will often hear abortion advocates lead with something about “the decision to have an abortion should be between a woman and her doctor.” This is a relic from the 1960s and 1970s when public opinion was against the legalization of elective abortion. Unable to get a poll to show public support for the legalization of elective abortion, some abortion advocates found that the “between a woman and her doctor” type questions garnered more positive reactions.

It is likely the “between a woman and her doctor” type questions elicited more positive responses because the framing of “a woman and her doctor” evokes cases in which abortion is sought because of threats to the mother’s health, and abortion in the case of preserving the health of the mother was (and is) the reason for abortion with the greatest approval.

For instance, in a previous article, I found that an outlier among polls for the 2025 Virginia gubernatorial election found a 10 percentage point lead for the Democratic candidate, while other polls found a tie between the Republican and Democratic candidates. It turns out that the outlier poll simply had more Democrats respond to it than Republicans, and the poll did not adjust its results for partisan affiliation.

For transparency, I used to work as a survey statistician, but I worked for a competitor and not NORC.

The GSS uses an address-based sampling frame; Gallup uses telephone-based sampling. The GSS is transparent with numerous publicly available papers about its methodology; Gallup keeps much of its data and methodology to itself and its paid subscribers. The GSS, up until recently, used in-person interviews; Gallup interviews respondents over the phone.

Polls run via telephone and have obvious issues. Households without telephones are missed entirely, while households with multiple telephone numbers are more likely to be selected. This can partially be addressed in weight adjustment.

They were actually done at Judith Blake’s request from 1968 onwards, while the first three were done without her request.

The six questions on the NFS were:

I'm going to read to you a list of six possible reasons why a woman might have a pregnancy interrupted. Would you tell me whether you think it would be all right for a woman to do this:

A. If the pregnancy seriously endangered the woman's health?

B. If the woman was not married?

C. If the couple could not afford another child?

D. If they didn't want any more children?

E. If the woman had good reason to believe the child might be deformed?

F. If the woman had been raped?

The six questions on the NORC surveys were:

Please tell me whether or not you think it should be possible for a pregnant woman to obtain a legal abortion if…

there is a strong chance of serious defect in the baby?

she is married and does not want any more children?

the woman’s own health is seriously endangered by the pregnancy?

if the family has a very low income and cannot afford more children?

she became pregnant as the result of rape?

she is not married and does not want to marry the man?

Support for legalized abortion in the case of a couple that does not have enough money was a minority position in the NFS surveys. By extrapolation, it is probably a minority position in the Gallup/Blake polling, as well, though Blake does not report the results after 1969 in her paper. It was barely a majority position on the GSS, which reported higher approval for legalized abortion than the other two sources. Given all of this, it was probably a minority position in the 1970s, but given the ambiguity in the evidence, I refrain from discussing this case in the main text.

Recall that the 2021 and 2022 iterations have substantial methodology changes, which may have confounded these results somewhat.

In this analysis, I have grouped self-identified independents who tend to vote Republican with self-identified Republicans and self-identified independents who tend to vote Democrat with Democrats.

Even if the change in results from the 2018 GSS to the 2021/2022 GSS is due in part to the change in survey administration, Democrats had already reached a 63.1% approval of the legalization of abortion-on-demand in the 2018 GSS.

The few remaining independents or Republicans who would be enticed to vote for a Democrat because of abortion were allowed to split their vote for legalized abortion and Republican candidates in any state that had an abortion referendum.

If anything, the remaining abortion-sorting favors Republicans in some very specific subdomains, such as in majority-Latino districts that have voted Democrat but whose constituencies are opposed to abortion.

The Roe opinion states that viability occurs between 24 and 28 weeks, but I am guessing most people haven’t read Roe.

Thanks for this thorough analysis, Joshua. Abortion on demand was not part of early feminism, but it was a policy of Bolsheviks who wanted young women in the military and the factories, to bolster the Soviet Union's rapid industrialisation. That could have been achieved by punishing men who used women for sex, but the regime chose to apply the costs of unwanted pregnancy to women instead. The authoritarian Left is essentially a top-down, men's rights movement which guarantees access to women's bodies without parental responsibilities.

Figure 9 in this article is especially interesting because it shows divergence in public opinion at two specific points in history: in 1990 after the collapse of European communism, when the Left switched allegiance to postmodernism including 'sex-positive feminism', and accelerating in 2010 after the credit crunch, when corporations abandoned their notional support for majority democratic principles to become 'woke' vanguards of political culture.