Abortion Was the "Defund the Police" of the 1960s

About 80% of Americans rejected elective abortion, and women did so at a higher rate than men.

Introduction

The strikingly negative views expressed in these surveys toward pregnancy termination for economic and discretionary reasons naturally make one wonder how the liberalization of abortion will ever come about.…

Legalized abortion is supported most strongly by the non-Catholic, male, well-educated “establishment." I have explained this finding in terms of the occupational and familial roles that such men play, in contrast with the roles performed by women in their own class, and by men and women in classes beneath them.

…it is to the educated and influential that we must look for effecting rapid legislative change in spite of conservative opinions among important subgroups such as the lower classes and women. But these subgroups will not necessarily accord widespread approval to the practice of discretionary abortion, nor is it clear that the population generally will do more than tolerate abortion as a necessary evil — even if it is relied on extensively as a stopgap measure. This popular ambivalence, plus the cumbersomeness of state-by-state change in abortion laws, suggest that a Supreme Court ruling concerning the constitutionality of existing state restrictions is the only road to rapid change in the grounds for abortion.…

Hence, if we heeded only the fact that 80 percent of our … population1 disapproves [of] elective abortion, our expectations concerning major reform would be too modest. We must also take into account the more positive views of a powerful minority…

-Judith Blake (1971)

Symbolic Capitalism and “Defund the Police”

What Musa al-Gharbi calls the “symbolic capitalist” class of the United States — our researchers, journalists, publishers, teachers, professors, and administrators — has often championed causes supposedly on behalf of disadvantaged classes. However, the symbolic capitalists rarely actually learn what people of their championed disadvantaged class actually want. Instead, they are more likely to promote ideas trendy among the symbolic capitalists themselves.

For instance, in the summer of 2020, many of the symbolic capitalist class of the United States discussed the proposition to “defund the police” to combat police misconduct. While this idea was an active topic among the symbolic capitalists, it was a complete non-starter among the American people. According to a survey conducted on June 16-22 by the Pew Research Center, 73% of Americans believed that police funding should either be increased or stay the same, compared with only 25% who believed it should be decreased.

Even among the Black Americans that many of the symbolic capitalists believed they were championing, only 42% of Black adults believed that spending on police should be decreased, compared with 55% of Black adults who believed it should either increase or stay the same.

A follow-up survey in 2021 found that public opinion had further moved against “defund the police.” A full 84% of Americans believed that spending on police should be increased or stay the same, compared with 15% of Americans who believed it should be decreased. The proportion of Black adults who believed police funding should be decreased had plummeted to 23%.

The “defund the police” idea never had much traction with the American public, even at the peak of its trendiness. Moreover, the “defund the police” idea wasn’t popular even among the people that the trendy symbolic capitalists claimed to be championing — Black Americans.

As we will see, the legalization of elective abortion was in a very similar situation in the 1960s to “defund the police” in the 2020s. Many of the symbolic capitalist class acted as cheerleaders for the proposition of legalizing and destigmatizing elective abortion. The vast majority of the American public, however, rejected the proposition.

The situation was even worse for elective abortion in the 1960s than “defund the police” in the 2020s. At least in the 2020s, a greater proportion (though still a minority) of Black Americans supported “defund the police” than did Americans generally. However, in the 1960s, fewer women supported elective abortion than did men, even though abortion activists advocated elective abortion as women’s liberation.

Cultural Hegemony

It has become fashionable in heterodox spaces to decry that our symbolic capitalists espouse viewpoints on race and gender beloved only by a relatively small number of activists. Because of this, our symbolic capitalists themselves behave more like activists rather than people impartially pursuing truth or disseminating information.

In a previous article, I noted that it is odd when heterodox individuals bemoan this capture of the symbolic capitalist class concerning race and gender ideologies, but fail to notice this capture when it comes to abortion.2 If anything, the capture of the symbolic capitalists by the abortion lobby is even more overt.

I attributed this to the process of cultural hegemony being farther along on the issue of abortion than on ideologies of race and gender. Unlike “defund the police,” abortion demagoguery has become mainstream.

Prospectus for This Series of Articles

This is the first article in a series analyzing public opinion on abortion in the United States. This is a topic interesting in its own right, but is also a case study on how the phenomenon of cultural hegemony in the United States works.

This first article focuses exclusively on the 1960s for several reasons.

First, with one major exception, we don’t have access to the data for surveys before the 1970s. Many results reported in this article are therefore results taken verbatim from tables in papers published in the academic literature.

Secondly, understanding American public opinion on abortion in the 1960s is an important baseline for understanding the trends in changes in public opinion that came after. Public opinion in the 1960s was overwhelming, whereas public opinion afterward was often mixed. Starting in the 1970s would lead to a lack of context.

Thirdly, I want to take this article as an opportunity to discuss a specific paper by Judith Blake (1971) at length. The 1970s were a turning point for the abortion lobby, and the Blake paper is an interesting insight into why the abortion lobby became what it did.

Sources

The results I report here are from three sources:

A survey conducted by the National Opinion Research Center (NORC) in 1965, as reported by Evers and McGee (1980)

The 1965 National Fertility Survey (NFS)

A series of surveys conducted by Gallup from 1962 to 1969, as reported by Blake (1971)

The questions about abortion attitudes on the 1965 NORC survey were originally devised by Alice Rossi and reported upon by her in a chapter in a long out-of-print book. The questions would become included in the General Social Survey, which would be conducted regularly from 1972 on. Therefore, the 1965 NORC survey is an important comparison point for further analysis.

The 1965 NFS is the one source whose data I have access to. The target population of the NFS was currently married women. Therefore, the NFS can’t be used for comparisons of differences of opinion between the sexes, but I use it for other comparisons.

The Gallup surveys are the one source with repeated cross-sectional measurements in the 1960s. There are five surveys, the last three of which were done at the request of Blake herself.

Racism of “Abortion and Public Opinion” by Judith Blake

I am not fond of the frequent and spurious use of the term “racist” in today’s popular culture. Unfortunately, the paper by Blake (1971) is rather racist — not in the Robin DiAngelo \ Ibrham Kendi sense, but in the Jim Crow sense. Blake only reports on the opinions of White Americans.

Because of this and my lack of access to the underlying data, I repeat Blake’s results for White Americans in this article. I do not like this, and I would rather report results for all Americans as I do for my analysis of the 1965 NFS. (See the section “Why Only White People?” for further discussion.)

Results

All data sources support the same three conclusions about public opinion in the 1960s:

Americans overwhelmingly disapproved of abortion for monetary or discretionary reasons.

Americans overwhelmingly approved of abortion when the mother’s health was seriously endangered.

Americans were split on attitudes toward abortion in cases when there was a likelihood the child was deformed or when the pregnancy was conceived because the woman was raped, but a simple majority approved of abortion in these cases.

Gallup Polls

The target population of the Gallup polls was White Americans aged 21 and over who had access to a telephone and could respond to a poll in English. All of the Gallup polls asked these three questions:

Do you think abortion operations should or should not be legal in the following cases:

a. Where the health of the mother is in danger?

b. Where the child may be born deformed?

c. Where the family does not have enough money to support another child?

Additionally, the three polls in 1968 and 1969 added a fourth question:

d. Where the parents simply have all the children they want although there would be no major health or financial problems involved in having another child?

A majority of White Americans disapproved of the legalization of abortion for the reasons of money (68% in 1969) and not wanting more children (79% in 1969). However, a minority of White Americans disapproved of the legalization of abortion in the case of the mother’s health (13% in 1969) and if the child is likely to be deformed (25% in 1969).

1965 National Fertility Survey (NFS)

The target population of the 1965 NFS was currently married women in the United States under age 55.3

The 1965 NFS included these six questions:

I'm going to read to you a list of six possible reasons why a woman might have a pregnancy interrupted. Would you tell me whether you think it would be all right for a woman to do this:

A. If the pregnancy seriously endangered the woman's health?

B. If the woman was not married?

C. If the couple could not afford another child?

D. If they didn't want any more children?

E. If the woman had good reason to believe the child might be deformed?

F. If the woman had been raped?

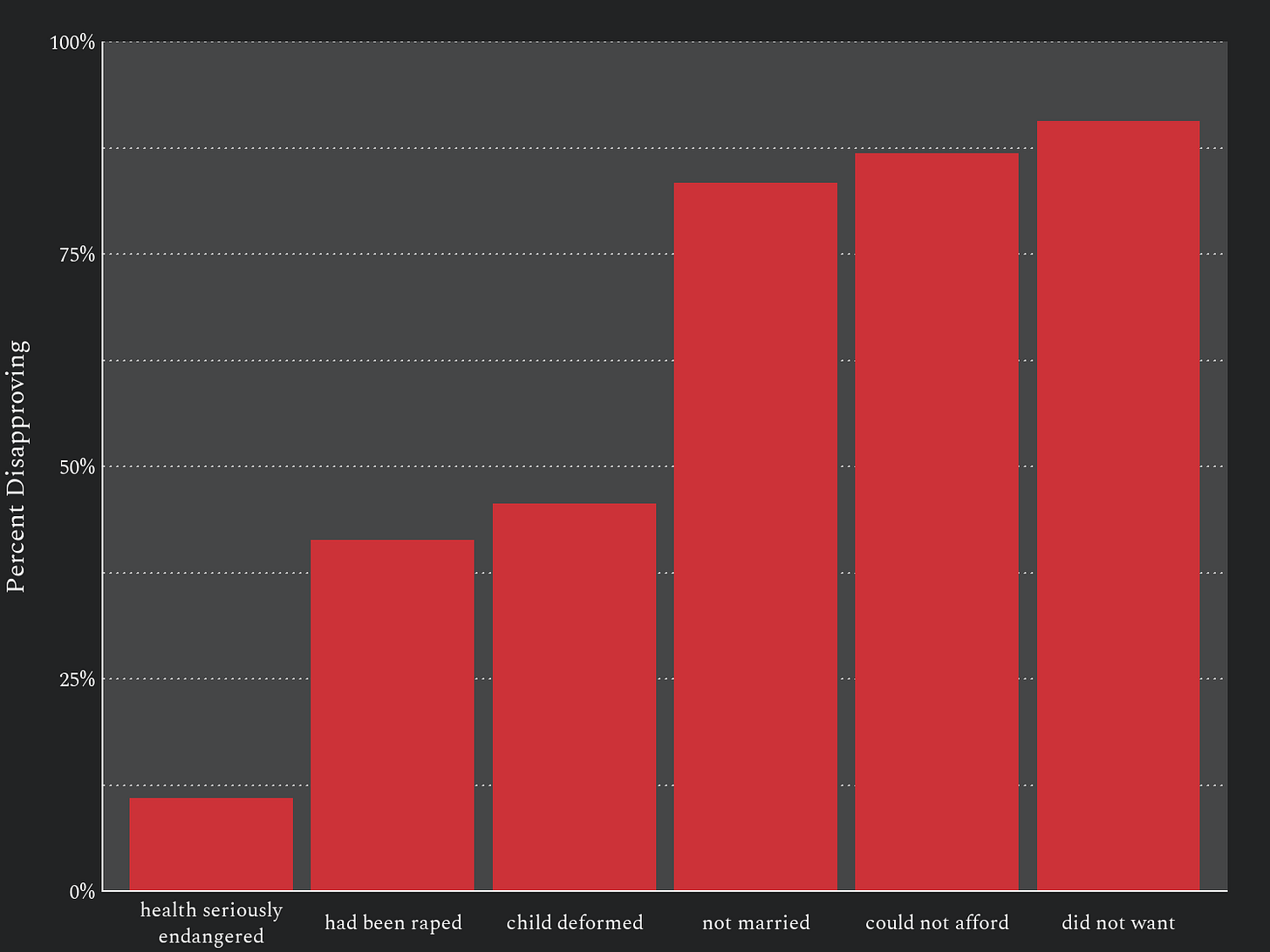

Majorities of American married women in 1965 disapproved of abortion when couples did not want any more children (91%), when couples couldn’t afford more children (87%), and when a woman was unmarried (84%). Sizable minorities disapproved of abortion when a child was likely to be deformed (46%) or a woman had been raped (42%). A tiny minority disapproved of abortion when a pregnancy seriously endangered a woman’s health (11%).

1965 National Opinion Research Center (NORC) Survey

The target population for the 1965 NORC survey was all adult Americans.4 Unlike Gallup polling, which is based on telephone calls, NORC used address-based sampling, which is considered more reliable in the survey statistics profession.

The six questions about abortion attitudes in the 1965 NORC were:

Please tell me whether or not you think it should be possible for a pregnant woman to obtain a legal abortion if…

the woman’s own health is seriously endangered by the pregnancy?

there is a strong chance of serious defect in the baby?

she became pregnant as the result of rape?

if the family has a very low income and cannot afford more children?

she is not married and does not want to marry the man?

she is married and does not want any more children?

Results are reported by Evers and McGee in terms of approval, rather than disapproval as does Blake.

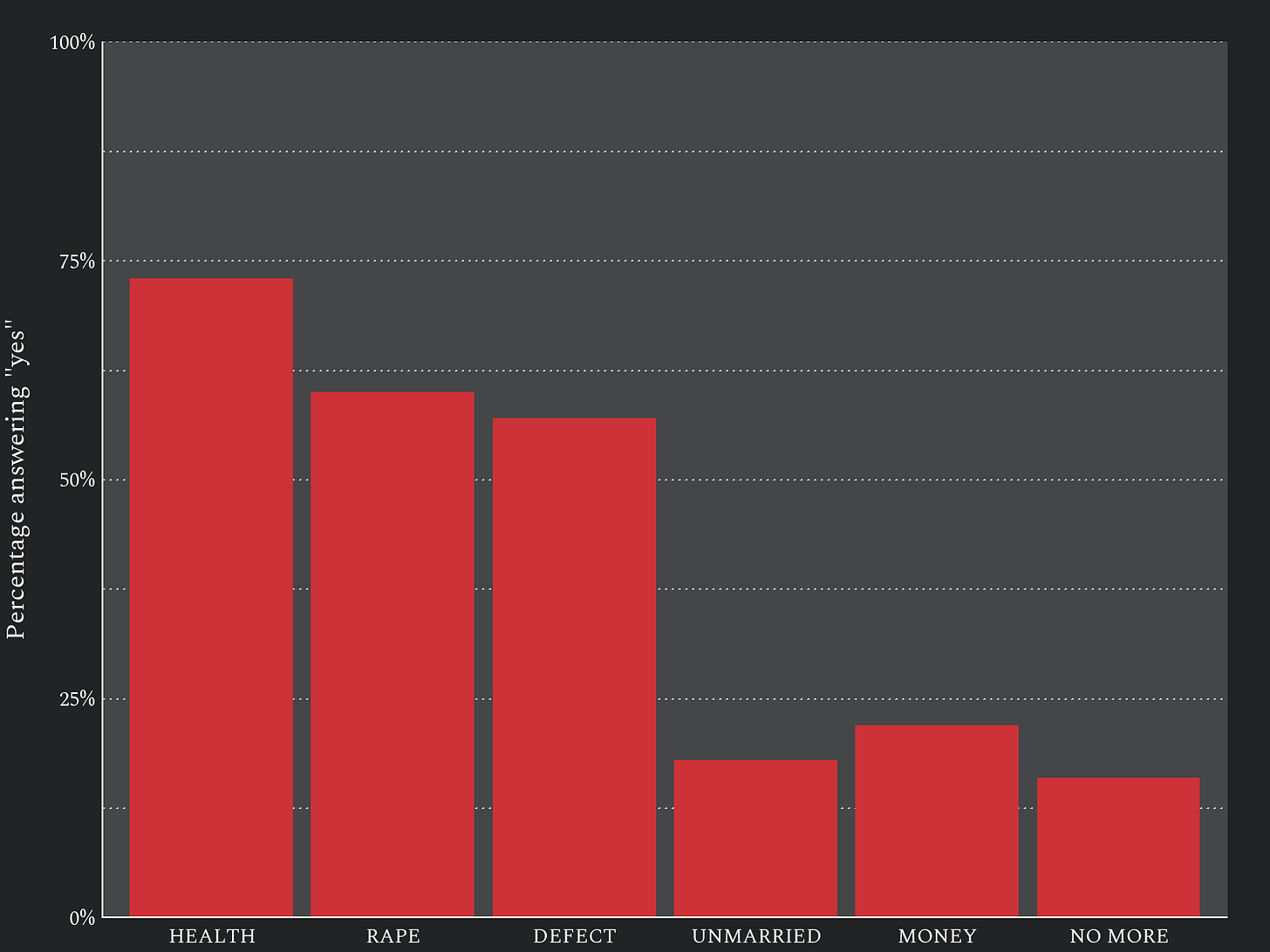

Small minorities of Americans approved of legal abortion in the cases of not wanting more children (16%), a woman being unmarried (18%), or not being able to afford more children (22%). Majorities of Americans approved of legal abortion in the cases of a baby having a serious defect (57%) and of a woman having been raped (60%). An even larger majority of Americans approved of legal abortion in the case of a woman’s health being seriously endangered (73%).

Discussion

In all results, Americans of the 1960s had very high disapproval of abortion for discretionary reasons. Similarly, Americans had very high approval of abortion if the mother’s health was in serious danger. Attitudes toward abortion in the cases of serious fetal defect and rape were more mixed, but a simple majority of Americans approved of abortion in these cases.

This was consistent with the vast majority of Americans of the 1960s judging abortion to be a form of homicide. Legal homicide is typically reserved for exceptional cases such as its use to protect a person from imminent threat of death or serious bodily injury. Thus, overwhelming support for abortion in the case of the mother’s health being seriously endangered was consistent with existing justified homicide law.

Indeed, criminal abortion statutes were enacted as part of state criminal homicide statutes. (Gump 2023)

Severe fetal deformity was an active topic in the public discourse of the early 1960s as the United States grappled with the effects of the drug thalidomide being prescribed to pregnant women in the late 1950s and early 1960s. This led to thousands of babies being born with severe deformities.

Similarly, the fact that the ugly and heinous act of rape sometimes leads to pregnancy was a topic of public discourse in the early 1960s.

It appears that Americans of the 1960s were willing to add severe fetal deformity and pregnancy resulting from rape to the list of exceptional cases when abortion — judged to be a form of homicide — should be acceptable. The newness of these justifications is likely the cause of the lower rates of approval when compared with abortion when the mother’s health is seriously endangered by the pregnancy.

The American public in the 1960s did not accept that abortion was a harmless act like having an appendix removed. This can be seen in public opinion overwhelmingly rejecting abortion in cases judged to be unexceptional, such as when unmarried women become pregnant, families are poor, or couples do not want more children.

It appears that there was more opposition to abortion for monetary reasons in the 1965 NFS than in either Gallup polling or the 1965 NORC survey. Married women surveyed by the 1965 NFS disapproved of abortion for monetary reasons at a rate of 87%, but White Americans disapproved of abortion for monetary reasons at only a rate of 74% in the Gallup poll of 1965. Furthermore, Americans positively approved of abortion for monetary reasons in the 1965 NORC survey at a rate of 22%. Thus, there appears to be a 10 to 15 percentage point difference between the 1965 NFS and other surveys from the same year.

There are several hypotheses for this discrepancy. One is that married women disapproved of abortion at a higher rate than the general population. Due to data limitations, I cannot test this hypothesis, but we will see in the next section that women generally disapproved of abortion at a higher rate than men in the 1960s.

Another hypothesis is that the wording of the NFS made a difference. The NFS asked if abortion “would be all right.” The Gallup polls asked if abortion “should or should not be legal,” and the NORC survey asked whether “it should be possible for a pregnant woman to obtain a legal abortion.” It is possible that “all right” makes respondents think about a moral judgment compared with “legal,” which is certainly a prescription about the law.

If this were the case, then it was also possible for there to be a (relatively small) number of respondents who judged abortion to be morally wrong, but legally permissible. This would account for the 10 to 15 percentage point difference. However, due to data limitations, this hypothesis cannot be tested.

Women’s Opinions

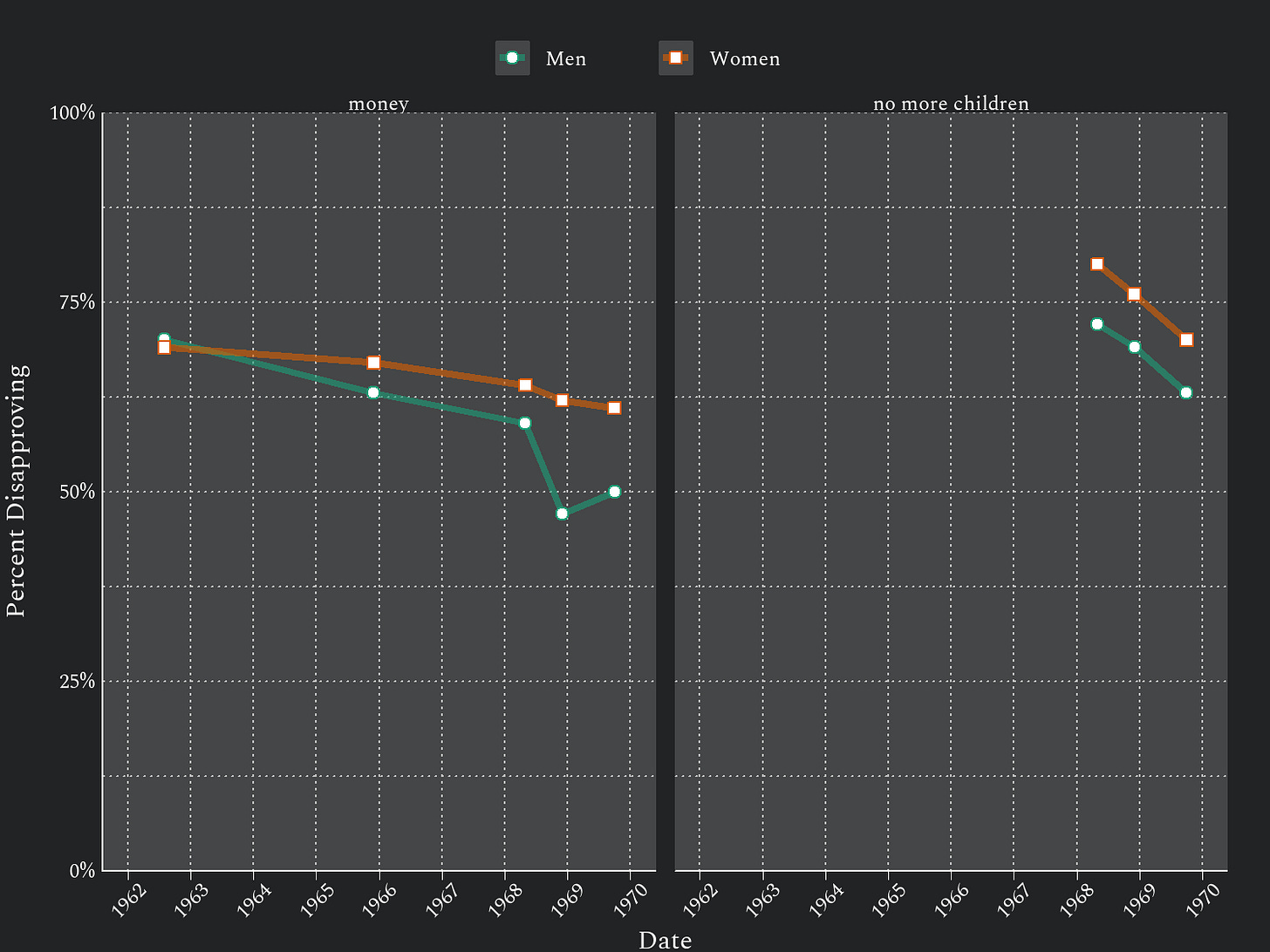

Women generally had a higher rate of disapproval of abortion than men in the 1960s. However, the overall difference was small. For instance, the difference in disapproval rate between women and men in the case of child deformity ranged from 2 percentage points to 5 percentage points in the Gallup polls. In May 1968, women’s disapproval rate (10%) for abortion when the mother’s health is endangered was actually lower than men’s (11%), but that is the only exception out of 18 comparisons.

The difference in women’s and men’s disapproval rates may or may not have been statistically significant. Blake only reports the total number of respondents to each poll. The numbers of men and women respondents are needed to check statistical tests.

Blake points out that disapproval of abortion when a family does not have enough money dipped below 50% among non-Catholic, White, college-educated men in December 1968. It was 47%. This is notable as the only demographic subdomain that had less than majority disapproval of any discretionary abortion case in all of the Gallup polling of the 1960s.

In the same poll, non-Catholic, White, college-educated women disapproved of abortion for monetary reasons at a rate of 62%. This 15 percentage point gap was one of the largest between women and men in the Gallup polling. In the next poll, the gap narrowed to 11 percentage points but remained substantial (61% disapproval among women versus 50% disapproval among men).5

While the difference in opinion on abortion between women and men was overall small, in specific subdomains it was larger.

One thing is clear: in the 1960s, abortion was not favored by women more than men.

Catholics’ Opinions

Differences in disapproval rates between Catholic and non-Catholic White Americans ranged from 2 percentage points to 12 percentage points for discretionary cases in Gallup polling. These differences were not enough to make the three-tiered trend in public opinion results among non-Catholics substantively different from those of the general population.

The 1965 NFS corroborates this result. Disapproval rates are higher in all cases among Catholic married women than among non-Catholic married women, but these differences do not change the overall three-tiered trend in responses.

Non-Catholics overwhelmingly disapproved of abortion in discretionary cases while overwhelmingly approving of abortion when the mother’s health was seriously endangered.

Opposition to elective abortion was not just a Catholic phenomenon.

Differences in Opinions by Region

There were some regional differences in public opinion about abortion in the 1960s. Married women near the coasts of the United States (Northeast and Far West) were slightly less likely to disapprove of abortion. Married women in the South had higher rates of disapproval of abortion. Public opinion of married women in the Midwest was in between.

Again, these regional differences were small compared to the overwhelming disapproval in all regions of abortion in discretionary cases and overwhelming approval of abortion in the case of the mother’s health being seriously endangered.

Differences in Opinions by Education Level

In all cases asked about by the 1965 NFS, married American women who received any college education had a lower rate of disapproval of abortion than those who had not received any college education. Similarly to other demographic subdomains, however, these differences pale in comparison to the overwhelming disapproval of abortion in discretionary cases.

Differences in Opinions by Age Group

In responses to the 1965 NFS, younger married women generally had a higher rate of disapproval of abortion than older age groups. However, I caution against interpretation of these results. When I fitted logistic regression models to the NFS data with all of the explanatory variables discussed in this article, most of the estimates of coefficients for the age group variables were not statistically different from zero. Differences supposedly due to age are likely confounded by other variables that better explain the differences.

Blake found similar results in the Gallup polls. Generally, younger people seemed to have higher disapproval of abortion, but this did not always hold.

Discussion of “Abortion and Public Opinion” by Judith Blake

As seen in the opening quote, Judith Blake’s 1971 paper “Abortion and Public Opinion” was less of a scholarly paper reporting on public opinion about abortion and more of an advocacy paper for the legalization of abortion.

Who was Judith Blake? Given the nature of her paper, was she an employee of the National Abortion Rights Action League (NARAL)?

No, Judith Blake was “professor of demography and chairman of the Department of Demography” at the University of California, Berkeley. Her paper was published in the prestigious journal Science.

The paper by Blake is unapologetically a political strategy screed. She represents the opinions of only her side of an issue, then proceeds to try to figure out how her side can get their way even though 80% of Americans reject their platform.

Furthermore, she did this consciously and intentionally. She knew that 80% of Americans rejected her position because that was what the paper was about.

This was a paper published in the journal Science, not the journal Unpopular Opinions of University Professors. Yet there was no pretense that her paper even aspired to be a scientific inquiry. There was no dispassionate, values-free inquiry to find the truth and disseminate knowledge in an unbiased way. Indeed, there was nothing but bias.

Not only was Judith Blake supposed to be a scholar, not a political activist, but she was a scholar at a public university. Taxpayers were paying the salary of someone who was actively conniving on how to overcome the will of the majority of taxpayers.

Blake’s paper was published in 1971. This corruption of our symbolic capitalists is at least fifty years old. The people who hold the keys to the kingdom of knowledge generation have been abusing their positions for over half a century.

This is why the “trust The Science™” rhetoric favored by many conformists is a joke. Advocacy of any political position — let alone one rejected by 80% of Americans — is not science in any true sense of the word, but this is “The Science™” that conformists want us to “trust.” This is not a request for trust, but a demand for submission.

Why Only White People?

The reason why Blake’s paper was so blatantly racist was precisely because it was a political strategy screed and not science. Blake spent most of the paper looking very hard for a demographic subdomain that had a majority approving of elective abortion. White people tended to disapprove of abortion at a lower rate than people of other races.

Thus, Blake probably examined the opinion of just White people to try to get the most favorable opinions about abortion she could.

However, it likely did not matter much. I fit logistic regression models to the 1965 NFS data with each abortion attitude variable as a response variable and with all the variables described in this article as explanatory variables. The estimates for the coefficients of the race variables were not statistically different from zero for the discretionary abortion cases (“not married,” “could not afford,” and “did not want” in the graph above).

Since the NFS population was married women and the Gallup polling included men and unmarried women, it is still possible that the differences in opinion between White people and people of other races were statistically significant in the Gallup polling. However, given the overwhelming disapproval of elective abortion in the 1960s, this would have made a very small difference, if any.

Nonetheless, it is jarring to see just how blatantly racist abortion advocates of the 1970s could be.

Foreshadowing of Judicial Activism and Cultural Hegemony

The paper by Blake is interesting as a historical document. It was written at a time when the abortion lobby was pivoting from an approach in the 1960s of working within democratic norms to an approach of extra-democratic judicial activism.

Blake bemoaned that “the population generally will do more than tolerate abortion as a necessary evil.” This caused her to suggest that “the only road to rapid change in the grounds for abortion” was “a Supreme Court ruling concerning the constitutionality of existing state restrictions.” This of course foreshadows the Supreme Court opinions Roe v. Wade and Doe v. Bolton that would be issued less than two years later and effectively overturn the abortion laws of all fifty states.

The paper by Judith Blake also explicitly advertised abortion advocacy as a classic example of the cultural hegemony phenomenon in effect. A “powerful minority” of “establishment” Americans who had outsized influence on the culture were able to push their views down onto the majority of Americans “beneath them” and make their views mainstream.

Feigned Ignorance of Motives for Opposition to Abortion

Throughout her paper, Blake refuses to acknowledge the real reason that 80% of Americans were opposed to elective abortion. Instead, she ascribes “state laws on abortion” to “the more repressive of our pronatalist policies.” This is a lie common in the demagoguery of abortion advocates to this very day.

As I have already mentioned in this article and discussed in a previous article, state abortion laws were part of the criminal homicide statutes and were drafted in the wake of scientific discoveries making the English common law criterion of quickening obsolete.

Indeed, Blake refuses to acknowledge that the higher rate of disapproval of elective abortion among women had anything to do with a moral judgment against what Planned Parenthood founder Margaret Sanger described as women’s natural aversion to “killing babies in the womb” and “the murder of unborn children.” Instead, Blake condescendingly describes women thus:

Among people who have few independent ways of feeling important, being an object of institutionalized restraint indicates that "somebody" cares how they behave, that they have not been totally forgotten.

According to Blake, women liked having their “freedom restricted” because it made them feel important.

But Blake also briefly let slip that she knew that moral opposition to abortion existed:

The difference in the introductory wording to the questions apparently resulted in less acceptance of abortion among respondents to the National Fertility Study than among respondents to the Gallup surveys (except in the case of the "mother's health"). In the National Fertility Survey, respondents were asked whether they would approve an action (that is, termination of pregnancy under a given condition with no mention of its legal status). In the polls, respondents were asked whether they would approve making such action legal. Some respondents might well approve making abortion legal, while not approving an illegal termination of pregnancy. And some respondents may have interpreted the question in the National Fertility Study factually—as a query of whether abortion is in fact “all right” (that is, legal or morally acceptable, or both) under the conditions specified.

While Blake refused to acknowledge moral grounds for disapproving of abortion herself, she at least acknowledged that other women might have been acknowledging the existence of such moral grounds in their responses to the NFS.

As I have written about in a previous article, this tactic of not even acknowledging there is moral opposition to abortion is common among the shills of the abortion lobby who are employed as researchers. Judging by Blake’s example, it got started at least a half-century ago.

Conclusion

One of the more insufferable practices of self-styled “progressive” activist groups is the practice of portraying themselves as the “resistance” against the oppressive establishment. At least when it comes to abortion, this is entirely backward. The abortion lobby is the establishment.

There was no grassroots groundswell of popular demand for elective abortion in the 1960s. There certainly was no grassroots popular demand for elective abortion among women, who disapproved of elective abortion at an even higher rate than men.

It is among White, college-educated, non-Catholic men that Judith Blake found the demographic subdomain most friendly to the program of liberalization of elective abortion. Even among this demographic, about half disapproved of legalizing elective abortion at the decade’s end.

However, this White, college-educated, non-Catholic, male demographic included most of the rich and powerful in American society in the 1960s. Indeed, it included some of the richest men in the world, such as John D. Rockefeller III and Warren Buffet, who funded the abortion lobby. (Forsythe 2013, pp. 61-62)

In subsequent articles in this series, I will explore how and when public opinion about abortion changed from the baseline of the 1960s.

References

Blake, J. (1971). Abortion and Public Opinion: The 1960-1970 Decade: Surveys show that Americans oppose elective abortion but in certain groups views are changing rapidly. Science, 171(3971), 540–549. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.171.3971.540

Evers, M., & McGee, J. (1980). The trend and pattern in attitudes toward abortion in the United States, 1965–1977. Social Indicators Research, 7(1), 251–267. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00305601

Forsythe, C. D. (2013). Abuse of discretion: The inside story of Roe v. Wade. Encounter Books.

Gump, D. (2023). Criminal Abortion Laws Across Before the Fourteenth Amendment (2nd edition). https://www.patreon.com/danielgump/

Blake writes “80 percent of our white population” here because her paper discussed exclusively the views of White Americans. Black Americans and Americans of other racial categories had higher rates of disapproval of abortion. See section “Why Only White People?” for more discussion.

Unless otherwise noted, in this article the word “abortion” is used to mean induced abortion of pregnancy.

Technically, the word “abortion” is a generic term. Any process that is aborted before it comes to completion can, in theory, be labeled “abortion.” However, because of its association with abortion of pregnancy and the emotional weight of such occurrence, the word “abortion” is usually used to mean abortion of pregnancy.

Furthermore, even if we just consider “abortion” to mean abortion of pregnancy, there is ambiguity because in the medical literature the word “abortion” is used to mean two different things: spontaneous abortion, which is commonly called “miscarriage” in the vernacular, occurs when a pregnancy terminates without anyone’s intervention; induced abortion occurs when a pregnancy is terminated on purpose. When “abortion” is used in the vernacular it is commonly used to mean induced abortion.

This ambiguity can lead to misinterpretation. For instance, if a study were to report on abortions in a given population, it could include both spontaneous and induced abortions if it were using the medical literature definition, but it could exclude what are commonly called “miscarriages” if it were using the common definition.

More specifically, the NFS population was currently married women, born after July 1, 1910, 55 years or younger at the time of the interview, living with their husbands, and able to participate in an English language interview.

More specifically, the NORC survey’s target population was all adult Americans who could respond to a survey in English.

Given the break of trend Gallup polling results for non-Catholic, White, college-educated men, the December 1968 likely involved some statistical error.

Thanks for writing this. You might want to connect with Black Tea News, and Feminists Choosing Life of New York, which are both on YouTube, if you haven't already. The key demographic you have identified, white, college-educated men, have multiple vested interests in the supply-side of abortion, as tax payers, employers and as careless reproducers. This is why the media class has very little to say about the demand-side, and why technologically advanced societies have millions of unwanted pregnancies each year.