Gender Critics Shouldn't Take a Victory Lap Just Yet

A NYT/Ipsos poll finds that ~80% of Americans disapprove of transgender athletes in women's sports and puberty blockers for minors, but in 1969 Americans similarly rejected elective abortion.

The New York Times recently published “Support for Trump’s Policies Exceeds Support for Trump” which reported on a survey the Times commissioned with Ipsos.

The survey revealed just how out of touch Democrats are with the mainstream of American public opinion about two issues stemming from transgender activism.

Survey Question on Transgender Athletes

The poll asked respondents:

Thinking about transgender female athletes — meaning athletes who were male at birth but who currently identify as female — do you think they should or should not be allowed to compete in women's sports?

An overwhelming majority (78.8% ± 2.6%)1 of Americans answered that transgender athletes should not be allowed to compete in women’s sports.

Republicans rejected the proposition at a high rate (89.9% ± 2.6%). Furthermore, a majority of Democrats (66.6% ± 2.6%) disapproved of transgender athletes in women’s sports, as well.

Recent Vote on H.R. 28

This starkly contrasts with the recent vote of the U.S. House of Representatives on H.R. 28 - Protection of Women and Girls in Sports Act of 2025, which would prohibit schools that receive Title IX funding for their athletic programs from allowing biological males to compete in women’s sports programs.

Almost all House Republicans (216 out of 219) voted for H.R. 28, but nearly all House Democrats (206 out of 215) voted against H.R. 28. Only 2 Democrats voted for the bill.

Last year, shortly after the 2024 election, Representative Seth Moulton (D-Ma) questioned the Democrats’ commitment to transgender athletes in women’s sports, and he was decried as “transphobic” and a “Nazi cooperator.” Moulton voted against H.R. 28 along with his party.

Survey Question on Puberty-Blocking Drugs and Hormone Therapy for Minors

The survey also asked respondents:

Thinking about medications used for transgender care, do you think doctors should be able to prescribe puberty-blocking drugs or hormone therapy to minors between the ages of 10 and 18?

Results were a little more complicated because an intermediate “only minors ages 15 to 18” option was given.

Still, a majority of Americans (70.9% ± 2.6%) replied that doctors should not be able to prescribe puberty-blocking drugs or hormone therapy to anyone under age 18.

Again, this included a majority of Democrats (54.1% ± 2.6%).

Among the remainder of Democrats who did not outright reject puberty-blocking drugs for minors, more preferred the intermediate position (24.3% ± 2.6%) than agreed with the question (19.1% ± 2.6%).

Discussion

Perhaps you are part of the supermajorities on one or both of these issues. You might be happy to learn that there is broad bipartisan support among your neighbors for your viewpoint. You might even be ready to declare victory.

I caution against this.

I have no dog in this fight, as it were. I have not done enough research to have any strong opinions about the issues of transgender athletes in women’s sports or puberty-blocking drugs for minors.

What motivated me to write about the Times/Ipsos poll was that I was writing a series of articles on public opinion about abortion2 in the United States, and I was struck by how similar these poll results were to public opinion on elective abortion in the 1960s.

Much as how 70% to 80% of Americans are against transgender athletes in women’s sports and puberty-blockers for minors in 2025, 70% to 80% of Americans were against the legalization of elective abortion as late as 1969.

Three years later, Roe v. Wade and Doe v. Bolton happened. Over the half-century since then, the culture has changed. We now live in a world in which you can be fined a hundred thousand euros for describing abortion as a “cause of death” and be arrested for silently lowering your head in prayer within two hundred meters of an abortion clinic.

I am not asserting that this will necessarily happen for transgender issues, though it might. Perhaps one day, people might be fined large sums of money for using the “wrong” pronouns or be arrested for “misgendering” someone. People have already lost their jobs or been deplatformed for these reasons.

I think it is worth reflecting on how supermajorities of public opinion have far less influence on the culture of the United States than you might think, and it is worth considering both the similarities and differences between the situation for transgender activism in 2025 and the situation for abortion activism in 1969.

Similarities

Widespread Public Opposition (Initially)

The first similarity I already discussed: an overwhelming majority of the American public were against the legalization of elective abortion in the 1960s, and an overwhelming majority are against transgender athletes in women’s sports and puberty-blockers for minors in 2025.

Support from Wealthy Financiers

Both abortion activism in the 1960s and transgender activism in the 2020s have been funded by wealthy financiers. Indeed, abortion activism in the 1960s was funded by the richest men in the world, such as the Rockefeller family (John D. Rockefeller III and Nelson Rockefeller, in particular) and Warren Buffet. The financiers of transgender activism might not be quite that rich, but are still wealthy: Jon Stryker, Tim Gill, George Soros, the Pritzker family, et al.

Indeed, there is some overlap between the funding. The NoVo Foundation supports transgender activism and was created by Peter Buffet, son of abortion financier Warren Buffet.

Essentialist Reframing

Both abortion activism and transgender activism advance propositions based on philosophical essentialism. For abortion activism, this is “ a fetus is not a person,” etc. For transgender activism, this is “a transwoman is a woman,” etc.

The goal of both propositions is to make people reframe their thinking. This works only for people susceptible to essentialism, but that appears to be a great many people.

Once you accept the essentialism of “a fetus is not a person,” you are intellectually blocked from thinking about the moral ramifications of killing a human fetus. Once you accept the essentialism of “a transwoman is a woman,” then your thinking is rewired in a way that it is strange not to allow biological males in women’s spaces, rather than the converse.

Medicalization and Scientism

Self-styled “progressive” activists are apt to describe both abortion and transgender procedures in terms of “health care.” Thus, you hear them use shibboleths like “abortion care” and “gender-affirming care.” Indeed, I have seen papers in academic journals refer to abortion without using the word “abortion” at all, instead using “a medical procedure.”

This is part of a larger trend of the capture of organizations such as medical associations or research journals which can be used to issue official-sounding pronouncements. People vulnerable to arguments from authority are apt to trust “The Science™” and are susceptible to these rhetorical tricks because they lack the awareness that opinions have been rebranded as “science.”

Deplatforming, Misrepresentation, and Demagoguery

Because of the capture of journalism and research by self-styled “progressive” activism, both abortion and transgender issues are frequently demagogued.

Thus, instead of engaging in the substance of the debate on the moral status of a human fetus, mainstream media and academia often just deplatform one side of the issue and declare that the deplatformed “hate women” and are against “reproductive freedom.”

Similarly, you often see gender-critical people deplatformed from mainstream media and academia. Instead of being allowed to explain the substance of their concerns about transgender athletes in women’s sports or puberty blockers for minors, such people are denigrated as “bigots” who “hate trans people.”

Litigation Rather than Persusian

A tactical similarity between abortion activism and transgender activism has been the reliance on litigation rather than the persuasion of public opinion. Thus, there were Roe v. Wade and Doe v. Bolton for abortion and now there is United States v. Skrmetti for transgender activism.

There is a subtle difference between how the two activist movements proceeded historically, however. Abortion activism did try to persuade public opinion and work through normal democratic procedures at first. In the 1960s, nearly every state legislature in the United States debated abortion legislation. However, only three out of fifty states legalized elective abortion.

It was only after abortion activists realized they would not succeed in their goals through democratic norms that they turned to litigation and succeeded by way of the judicial activism of Roe and Doe.

Transgender activism seems to have learned from this earlier example and directly bypassed public opinion. This hasn’t necessarily meant focusing on litigation, either. Rather, transgender activism feels like it “snuck up” on a lot of Americans because it largely worked by changing corporate, academic, and government bureaucratic regulations and training rather than on achieving legislative victories.

Differences

Supreme Court Composition

This segues into the most obvious difference between abortion activism and transgender activism. Abortion activism took off during the Warren/Burger era of the Supreme Court in which the judicial activism of the “living constitution” was common. Therefore, abortion activism achieved a near-total political victory by way of Roe and Doe after only a few years.

Today, the United States Supreme Court has a 6-3 majority of Justices who subscribe to originalism, a theory of jurisprudence in which statutes are interpreted according to their original public meaning and not interpreted in ways to invent new laws. As long as this majority holds (which should be for a while, since Supreme Court appointments are for life), this precludes transgender activists from achieving the sweeping political victories that abortion activists did by litigation.

Decline of Trust in Institutions

Abortion activism has been a classic example of the cultural hegemony phenomenon working in American society. Influential people were able to dominate the culture and make their minority viewpoint mainstream.

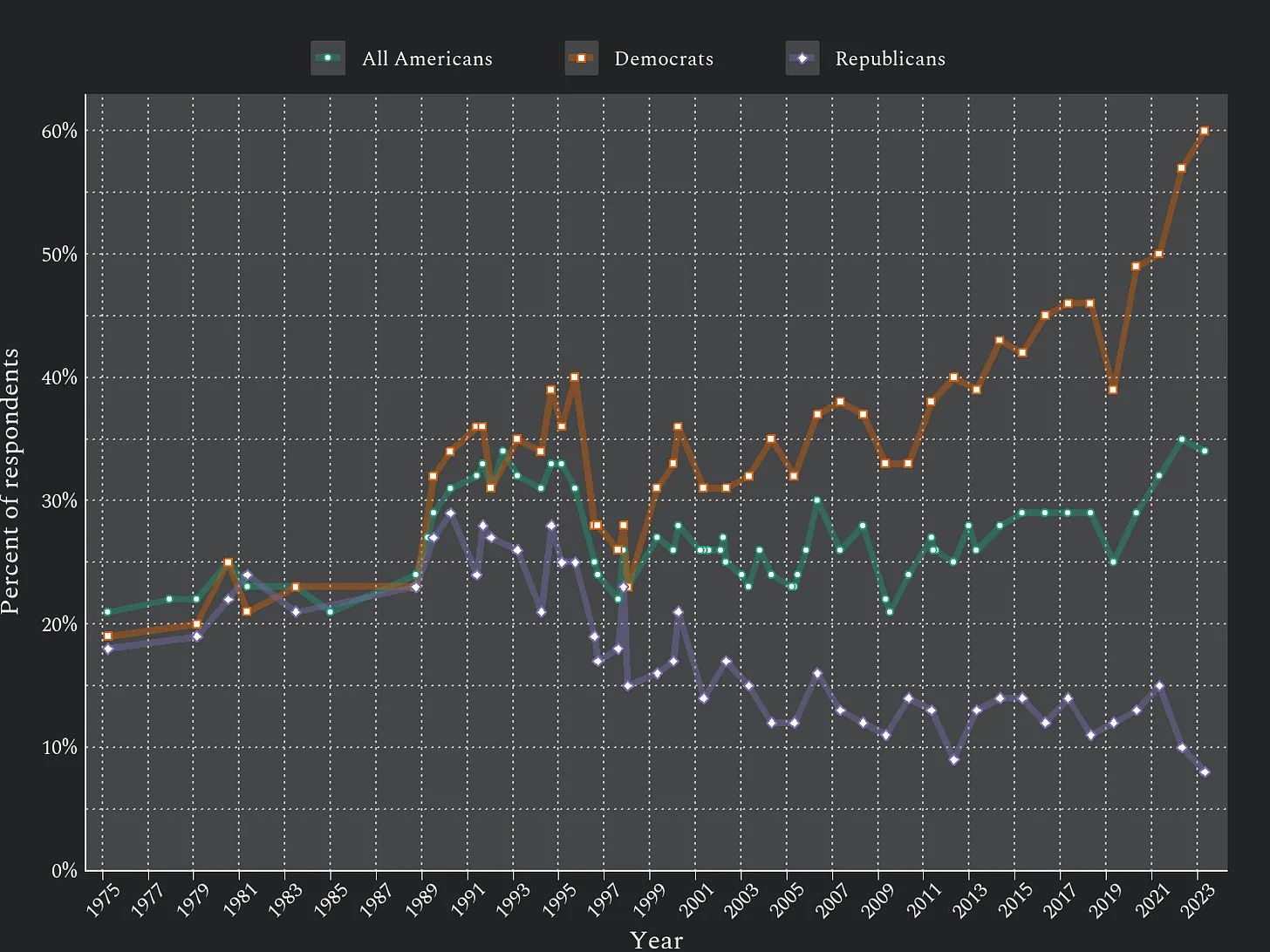

The cultural hegemony that abortion activism achieved was largely done through control of institutions such as mass media and academia. Abortion activism benefitted from the culture of the 1970s when public trust in institutions was relatively high. However, transgender activism exists in the contemporary culture in which public trust has plummeted.

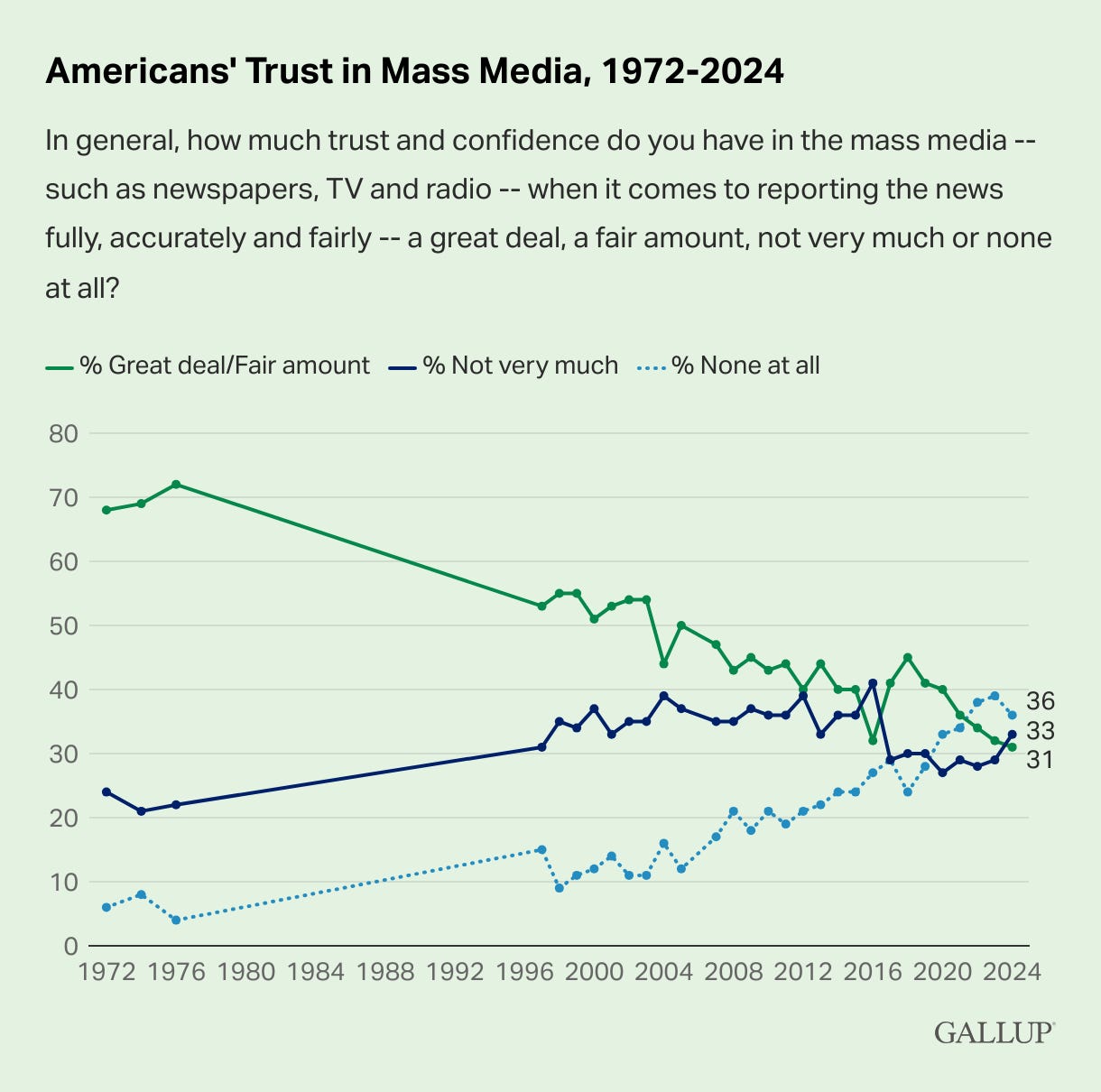

The decline in public trust in mass media since the 1970s is stark.

In the 1970s, ~70% of respondents to Gallup polling reported having a “great deal” or a “fair amount” of trust in the mass media, and less than 10% reported having “none at all.” Now, “none at all” is the most frequent response followed by “not very much.”

Gallup polling on confidence in academia goes only as far back as 2015, but indicates a declining trend, as well.

Therefore, transgender activism cannot leverage the capture of the mainstream media and academia to the extent that abortion activism has, simply because more people are wary of mainstream media and academia now.

Polarization by Political Party

As I have reported previously, there was not much polarization by political party on the issue of abortion until the 1990s. Before the partisan sorting, public opinion on abortion did not differ much between Democrats and Republicans, and politicians on both sides of the aisle were commonly either in favor or against the legalization of abortion.

Indeed, the aforementioned Rockefellers who financed the abortion legalization movement were “Rockefeller Republicans.” Nelson Rockefeller was the Republican Governor of New York and then Vice President of the United States under Gerald Ford. John D. Rockefeller III was chairman of a Presidential Commission on problems of population growth under Richard Nixon. (Forsythe 2013, pp. 58, 61-62)

The 1988 Democratic Party Presidential primaries were prescient of the partisan sorting about to occur. Of the seven Democrats3 seeking their party’s nomination, five had been against the legalization of abortion, but later changed their position to be in favor of legal abortion in the lead-up to the Presidential race.4

Today, viewpoints on abortion are highly polarized between Democrats and Republicans.

As we saw in the Times/Ipsos survey, viewpoints on transgender issues have already polarized between Democrats and Republicans. Even though the majority of Democrats answer both questions in the negative, the biggest gap in public opinion on the two questions is by partisan affiliation.

Therefore, most of the political wins of the abortion activists occurred before political polarization, but transgender activists must navigate a political landscape with polarization already in place.

Funding Pivot

In the section “Support of Wealthy Financiers,” I noted the wealthy donors behind abortion activism and transgender activism as a similarity between the two. However, there is one important, if subtle, difference in this comparison: the wealthy donors who have funded abortion activism have funded abortion activism per se, whereas much of the funding for transgender activism is a pivot from funding of advocacy for same-sex couples.

In short, much of the “LGBT” funding started off as “LGB” funding. As the activists themselves like to remind us, sexual orientation is different from gender identity. If the rich financiers are just as committed with their money to the “T” as to the “LGB” parts of their acronym, then this will amount to a difference that makes no difference. However, if wealthy donors are less committed to transgender activism per se and funding starts to dry up, this could pose a critical problem for transgender activists.

Activist Capture of Democrats

As I discussed in a previous article, some political platforms are popular with the general population. These can be used to attract persuadable voters and build a majority coalition for an election. Some platforms are popular only among a candidate’s own party. These can be used to rally the base and increase voter turnout preferentially among voters for your candidate.

Then there are positions like transgender athletes in women’s sports and puberty-blocking drugs for minors that are just losing positions for Democrats, at least at a national level. These positions are neither generally popular nor popular within the Democratic Party. On net, they lose votes for Democrats.

This is further evidence for the criticism by some Democratic strategists (for example, at The Liberal Patriot) that the Democrats have been captured by “the groups.” The criticism is that activist groups have too much power to set the platform for Democrats by way of cancellations, staffer uprisings, etc., such as what happened to Seth Moulton.

The capture of Democrats by “the groups” explains why the party would adopt a transgender platform so bad for their electoral chances. When self-styled “progressive” activists advance a position by way of cultural hegemony, they are not trying to set public policy to match public opinion per democratic norms. Rather, they are attempting to use public policy to change public opinion.

This is why people whose minds are dominated by a cultural hegemony are apt to speak of being “on the right side of history.” Whether something is “right” or not is a highly subjective value judgment, and asserting that your own viewpoint is the “right” one is circular nonsense. Whether self-aware or not, what such people are asserting is their faith in the belief that cultural hegemony will succeed and the opinions of the elites will eventually become the opinions of the masses.

Conclusion

The ideology of transgender activism bears some striking resemblance to the ideology of abortion activism. Both elective abortion and transgender athletes in women’s sports were rejected by 70% to 80% of Americans, at least initially. Both kinds of activism have been supported by wealthy benefactors, reframed thinking using essentialism, are rife with the rhetoric of medicalization and scientism, use tactics such as deplatforming, misrepresentation, and demagoguery, and favor litigation over persuasion.

The cultural hegemony of abortion activism has been remarkably successful. Activists took a viewpoint that was a minority viewpoint in the 1960s and made it a dominant viewpoint of not just the culture of the United States, but of much of the world.

It remains to be seen if transgender activists will also dominate the culture in the coming decades. There are many differences between the culture of the twenty-first century versus the culture of the twentieth century.

For example, in the United States, there is far more polarization in viewpoints on cultural issues based on political party affiliation. Americans trust in institutions such as academia and the mass media is far lower. Perhaps most importantly, the Supreme Court of the United States is comprised of a majority of Justices who reject judicial activism.

Because of these changes, if transgender activism ever does achieve cultural hegemony, it will necessarily have taken a different path to get there than abortion activism.

Appendix: Quality of Times/Ipsos Survey

When the Times/Ipsos survey results were released, I was surprised. The coverage of these issues by mainstream media, academics, medical associations, et al., is so biased in favor of the narratives of the activists that I wouldn’t have guessed that public opinion on these issues was so diametrically opposed to such narratives.

This caused me to take a closer look at the survey quality. Upon scrutiny, the Times/Ipsos survey is quite solid — much better than many of the polls whose results you see reported in mainstream media.

One of the most common issues with poll results you see in popular culture is that they are based on unrepresentative samples and are so useless for inference.

The survey used Ipsos’ KnowledgePanel. Selection for the KnowledgePanel uses addressed-based sampling. Addressed-based sampling is the most expensive kind of sampling, but is the state of the art for creating sampling frames.

The fact that KnowledgePanel surveys are administered through the Internet would introduce selection bias for households with Internet connections. However, KnowledgePanel households without Internet access are provided access, negating some of this selection bias.

Most surveys nowadays have very low response rates and suffer from response bias because of this. The sample taken for the Times/Ipsos survey was weighted to match totals for demographic categories taken from the American Community Survey and the Current Popular Survey of the U.S. Census Bureau, as well as the 2024 Presidential vote totals. This mitigates, but does not eliminate, response bias. This is much better than poll results that do not weight their results at all.

As in-person surveys have become increasingly prohibitively expensive in recent years, surveys such as the Times/Ipsos survey are effectively the new gold standard.

Furthermore, the folks at Ipsos reported a design effect and a sampling error in the form of a 95% confidence interval width, which makes me think they at least have professional survey statisticians working for them.

Another common issue with surveys is asking questions that are so open to interpretation that respondents’ answers actually mean different things from person to person. These are questions like whether people consider themselves “pro-choice” or “pro-life” or whether people want “a lot more,” “somewhat more,” “somewhat less,” or “a lot less gun control.” However, the two questions from the Times/Ipsos survey considered here are questions about specific policies, which avoids a lot of these issues.

Finally, the one criticism I have of the Times/Ipsos survey is that it is a one-off survey. I tend not to trust one-off survey results because survey responses on controversial issues tend to be very sensitive to how questions are worded and framed. Thus, a one-off survey does not tell you very much. The questions can easily be designed to elicit the responses that the people who commissioned the survey want.

Repeated surveys using the same questions are more telling because the use of the same wording for questions over time gives you an insight into changes in public opinion. Even if the choice of wording can bias results, once a survey commits to a certain wording, that functions as a baseline for tracking trends. However, one-off surveys can’t be scrutinized in this way.

References

Forsythe, C. D. (2013). Abuse of discretion: The inside story of Roe v. Wade. Encounter Books.

New York Times/Ipsos Survey, January 2-10, 2025. Topline & Methodology Report. Cross Tabulations.

Ponnuru, R. (2006). The Party of Death: The Democrats, the Media, the Courts, and the Disregard for Human Life. Regnery Publishing.

Ipsos reports a margin of error of 2.6 percentage points for all results to arrive at a 95% confidence interval.

Unless otherwise noted, in this article the word “abortion” is used to mean induced abortion of pregnancy.

Technically, the word “abortion” is a generic term. Any process that is aborted before it comes to completion can, in theory, be labeled “abortion.” However, because of its association with abortion of pregnancy and the emotional weight of such occurrence, the word “abortion” is usually used to mean abortion of pregnancy.

Furthermore, even if we just consider “abortion” to mean abortion of pregnancy, there is ambiguity because in the medical literature the word “abortion” is used to mean two different things: spontaneous abortion, which is commonly called “miscarriage” in the vernacular, occurs when a pregnancy terminates without anyone’s intervention; induced abortion occurs when a pregnancy is terminated on purpose. When “abortion” is used in the vernacular it is commonly used to mean induced abortion.

This ambiguity can lead to misinterpretation. For instance, if a study were to report on abortions in a given population, it could include both spontaneous and induced abortions if it were using the medical literature definition, but it could exclude what are commonly called “miscarriages” if it were using the common definition.

It is easy to remember that there were seven candidates for Democrats in 1988 because they were nicknamed “the seven dwarfs.”

Dick Gephardt had co-sponsored a Constitutional amendment to ban abortion in 1977. Jesse Jackson, also in 1977, asserted that “the position that life is private … was the premise of slavery.” Joe Biden had voted to amend the Constitution to reverse Roe and Doe. Paul Simon had in 1981 introduced a resolution in Congress to allow the several states to ban abortion. Al Gore voted for an amendment to the Civil Rights Act of 1984 that would have protected “unborn children from the moment of conception.” (Ponnuru 2006, pp. 21-22)