Online Survey Modes Lead to Declines in Survey Quality: A Case Study

There are anomalies in the 2022-2023 National Survey of Family Growth's online respondent data.

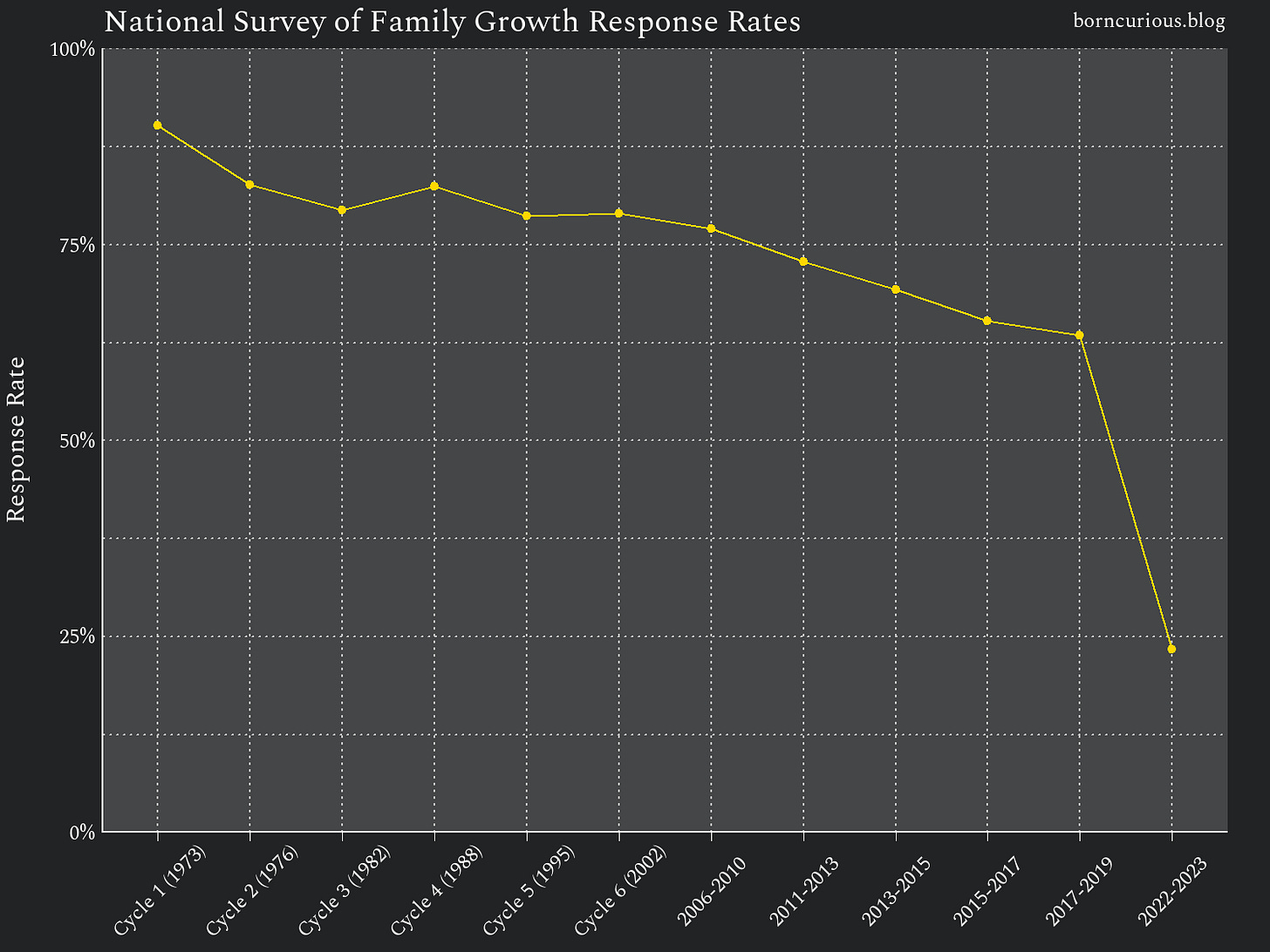

Declining (Then Plummeting) Response Rates

For over half a century, the “gold standard” for learning about real-world social phenomena has been a representative survey with an address-based sampling frame, probability-based sampling, and face-to-face (FTF) interviews.

Unfortunately, response rates to these “gold standard” surveys have steadily declined. Then, in 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic happened, and thereafter, response rates took a nosedive.

For instance, let’s look at what happened with the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG).

Response rates declined from ~90% in 1973 to ~63% in 2017-2019, but this was followed by a sudden drop of about 40 percentage points from a ~63% response rate in 2017-2019 to a ~23% response rate in 2022-2023.

It hasn’t just been the NSFG. The 2022-2023 NSFG User’s Guide states:

The NSFG response rates for 2022-2023 are markedly lower that the response rates for the last 2-year data collection period of 2017-2019. Some of the sharper decline in participation can be attributed to the effects on society of the COVID-19 pandemic, from respondents’ willingness to participate to the ability to recruit and retain interviewers.

Complex and long FTF surveys such as the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) that did not undergo major design changes from before the pandemic, also experienced drops in participation. For example, the NHANES unweighted interview response rate fell from 51.0% for the 2017-2020 data collection to 34.5% for 2021-2023. The examination response rates fell from 46.9% to 25.6%.

Other similarly long and sensitive household surveys to the NSFG, such as the National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) that underwent a redesign from only FTF to a web and FTF design, like NSFG, have also observed substantial drops in survey participation. The weighted overall survey response rate for NSDUH dropped from 45.8% in 2019 (pre-pandemic) to 12.3% in 2023.

As this passage alludes, there was a change in methodology between the 2017-2019 and 2022-2023 iterations of the NSFG when this dropoff in response rate occurred. The 2017-2019 NSFG used exclusively face-to-face interviews, but the 2022-2023 NSFG used a multimode sampling design that included both a Web-based form and face-to-face interviews.1

Plummeting response rates cause problems for surveys. They make surveys more expensive because larger samples must be drawn to get the target number of respondents needed for analysis. They also introduce more opportunity for response bias, the phenomenon in which respondents to the survey differ substantially from the survey’s target population.

Issue in 2022-2023 NFSG

When doing a recent analysis with NSFG data, I noticed an anomaly with the 2022-2023 NSFG public use data.

Since the NSFG is a fertility survey, it asks respondents whether they have ever had heterosexual, vaginal intercourse.2

If you look at people grouped by their birth cohort, you would expect the percentage of people who answer yes to this question to be strictly nondecreasing in subsequent surveys. The percentage of people born in certain years who have had intercourse should not decrease when asked in 2011 from what it was in 2006. You cannot undo having had intercourse.3

This is precisely what we see for three birth cohorts of women surveyed by the NSFG between 2006 and 2019.

Estimates of the percentage of women who have had sex by birth cohort increased for all three birth cohorts between the 2006-2010 and the 2011-2015 surveys. Point estimates appear to have declined between the 2011-2015 and 2015-2019 surveys for women born in the [1970,1975) interval,4 but this is well within fluctuations due to sampling error.

Now, let’s look at the trend including 2022-2023.

The 2022-2023 estimate for the percentage of women who have had sex appears much lower than the 2015-2019 estimate. Still, this strangeness could plausibly be explained by sampling error.

Looking at later birth cohorts, it becomes clear that mere sampling error does not explain this apparent and nonsensical decline.

So what is going on?

Part of the story is that the Web respondents to the 2022-2023 NSFG differ in their answers from face-to-face respondents.

In particular, women born after 1980 who responded to the 2022-2023 NSFG with a face-to-face interview reported having had sex a higher rate than women who responded via the online Web form.

If we exclude the Web respondents from our estimates for the [1980,1985) birth cohort, then the trends appear more plausible.

Using only face-to-face respondents, the dropoff in the percent of women who have had sex can plausibly be explained by sampling error for women born in [1980,1985) as seen in Figure 7, like it was for women born in [1975,1980) in Figure 4.

This phenomenon also exists among male respondents but is less dramatic. Curiously, it does not occur among cohorts born before 1980.

Response Bias or Measurement Error?

There are two plausible hypotheses for why Web respondents to the 2022-2023 NSFG would report a lower rate of sexual activity than face-to-face respondents among cohorts born after 1980.

Measurement Error: Under this hypothesis, people respond differently to an online survey than a face-to-face survey. In particular, responses are, on average, more honest in one mode or another.

Response Bias: Under this hypothesis, the people who respond to a survey online tend to differ from those who respond to a face-to-face survey.

Social Desirability

The Nuance Pill here on Substack took a look at the 2022-2023 NSFG data earlier this year and similarly noted anomalies with the online respondent portion of the data:

This could indicate two possibilities. One is the presence of social desirability bias, which might influence FTF responses more than the relatively anonymous online responses; the other is differences in characteristics between those who participated in the traditional FTF interview and those who completed the survey online.

Under this hypothesis, having had sexual intercourse is socially desirable, and people are less likely to admit that they have never had sexual intercourse when asked by a face-to-face interviewer.

The Nuance Pill seems to think this hypothesis is unlikely:

When it comes to social desirability bias, a few studies have found that online surveys are more susceptible to this than FTF interviews (Heerwegh, 2009; Berzelak & Vehovar, 2018). Interestingly, if it is having a large impact on the results, then women must be at least as ashamed to admit to being sexless as men, as women who completed the survey online had a similarly higher sexlessness rate to offline respondents as did men.

Social Aversion

A different hypothesis considered by Nuance Pill is that people who answer a survey via the Web tend to be more socially averse and so actually do have intercourse at a lower rate:

I found that online respondents were more educated and white on average, as were respondents in general compared to an earlier survey. One study found that online survey respondents were lower in openness to experience than FTF respondents, and this trait correlates with sexual activity.

While weighting can do a good job of accounting for these demographic characteristics, differences in personality/behaviour will likely remain, and there may be proportionally more people of a certain type than there were in previous samples…

False Negative Answers

I add a third hypothesis to Nuance Pill’s two hypotheses: people who answer a survey online might be more likely to lie. The NSFG offers a small monetary incentive, and it is a long survey designed to take 50 to 75 minutes to complete. Some people might just want the cash without having to spend an hour answering questions. If you say you haven’t had heterosexual, vaginal intercourse, you skip over most of the questions in the NSFG.

A little insider knowledge: having worked on the NSFG, I know that the survey administrators look for this and try to purge obviously fraudulent responses. However, nothing is perfect, and there may still be fake respondents who just want the $40 cash incentive slipping through.

This would also explain why the discrepancies are seen in younger cohorts, but not older ones. It is easier for younger people to pretend to have never had intercourse than for someone who is older, since by age 30, about 98% of people have had sexual intercourse.

Something about facing another human being who can read your demeanor and body language may make people less prone to lie. Also, people who intend to lie to get the $40 incentive with minimal effort might opt out of a face-to-face interview at a higher rate than an online survey, since letting someone into your home to interview you is more effort than using a Web browser.5

Conclusion

Surveys are moving away from the “gold standard” approach of face-to-face interviews to multi-modal approaches that primarily use online Web forms with face-to-face interviews as a backup. This is being done out of necessity due to rising costs from plummeting response rates and increasing difficulty hiring face-to-face interviewers.

We have reason to believe that online survey respondents either differ substantially from face-to-face respondents or are more apt to give false responses. If either is true, this compromises the veracity of comparing newer multi-modal iterations of surveys with previous face-to-face-only iterations. If the latter is true, this questions the veracity of the online responses themselves.

Going forward, we should exercise caution when doing any trend analysis that includes the time when a survey transitions from face-to-face-only to multi-modal, and we should express skepticism about online respondent data generally.

The NSFG hasn’t yet released more detailed response rates by mode of interview (face-to-face versus Web), but the fact that there was a greater decline in response rate for the NSDUH survey (~33 percentage points), which also changed to a multimode design, than for the NHANES survey ( ~16 percentage points) raises the question of whether people are less likely to respond to a Web-based survey than to an face-to-face interviewer. More detailed information about the sampling design is due to be released in the summer of 2025.

This is encoded in the HADSEX variable.

There is an obscure way this actually could happen. People who have had sexual intercourse could be dying between surveys at a higher rate than those who haven’t. This is unlikely to occur with such a disparity that it would affect the survey results, but it is possible.

The square bracket denotes that the interval is “closed” on the left and includes the year 1970, while the curved parenthesis on the right denotes that the interval is “open” on the right and does not include the year 1975.

This self-selection would make the fake-responses hypothesis both a measurement error and a response bias hypothesis.

Some food for thought: I was just thinking about why the GSS survey doesn't seem to show the same drastic mode difference (even after expanding the age range for a higher N) and thought back to the explanation you put forward here. The sex questions in the GSS are part of a small section (especially this time around it seems) which doesn't have the same 'say no then skip a bunch of questions' feature. I also don't think they offer a monetary incentive either.

Another possibility is that respondents who previously responded that they had heterosexual intercourse are now proud to be a 'gold star' lesbian or identify as asexual. It could be that they lied during earlier surveys due to social expectations, or that they have reframed their personal histories to support a current identity.