Part 3, Cultural Hegemony in the 21st Century

Political Realignment and Life as a Dissident

This is the third in a series of articles. Part 1 defined the concepts of cultural hegemony, common sense, and submission and provided examples of how these concepts can be observed empirically. Part 2 described the methods of cultural hegemony: institutional control, credentialism, deplatforming, and control of language.

Some would dismiss—without reasoning or argument—the criticism contained in this series of articles as “right-wing.” This is itself a symptom of cultural hegemony.

The Rhetoric of Progress

One way to manipulate common sense is to portray certain viewpoints as inevitable, when in reality they become popular because of hegemonic control over culture. Thus, a cultural hegemony will portray its preferred viewpoints as “progress” and appeal to the masses’ desire to be on the “right side of history.”

In reality, no change in public opinion is inevitable. Everybody thinks that their vision for society is “better” than the current state of society. If public opinion changed to match your views, this would be “better” to you and so constitute “progress.” A hegemony manipulates the rest of us into thinking that the hegemony’s viewpoints have a monopoly on “progress.”

Granted, a cultural hegemony will tend to be anti-traditionalist and anti-religious. Traditional values and religion are refuges of the old common sense. A cultural hegemony successfully achieves submission by replacing an older common sense with a new one that conforms to its desires. Therefore, a cultural hegemony views traditional cultural institutions as enemies that must be overcome.

Thus, the cultural hegemony of the 21st century in the United States is sometimes described as “progressive” or “left-wing,” and counter-hegemonic criticism is sometimes described as “conservative” or “right-wing.” However, this is itself a tactic used by the cultural hegemony.

The term left-wing emerged from the French Revolution to refer to those sitting on the left side of the National Assembly. It does not describe a distinct political philosophy. However, certain historical tendencies are associated with the term. It is used to describe concern about economic inequality, a desire for redistribution of wealth from the rich to the poor, workers’ movements, and a class-based analysis of society.

None of this is aligned with cultural hegemony. In fact, this original definition of “left wing” and our definition of cultural hegemony are directly opposed. The left wing is historically aligned with working-class interests against capitalist elites; however, cultural hegemony is staffed by the professional-managerial class (PMC), highly credentialed, and aligned with wealth—either directly from wealthy capitalists or from activist groups funded by wealthy capitalists.

Why, then, do the hegemonized claim the title of “left-wing?” We live in a stupidly partisan time, and invoking partisanship is a technique to shut down thinking and debate, because many of our contemporaries appear to have an us-versus-them mentality as an overriding motive.

The PMC of the United States consolidated into the Democratic Party in the 21st century (but not the 20th). The Democratic Party is considered the “left-wing” party of the United States. By labeling anything counter-hegemonic as “right-wing” or “conservative,” the hegemony leverages this base partisan mentality to dismiss a viewpoint without serious consideration simply because it comes from “the other side.”1

Why Cultural Hegemony Theory Matters

This brings us to why our theory of cultural hegemony is useful. My hypothesis is that we are living through a period of peak cultural hegemony. The hypothesis explains several things:

the current political realignment happening in American society, and

practical implications for dissidents.

Political Realignment

The Democratic Party of the United States was dominant in the 20th century. With brief interruptions, it controlled the U.S. Congress from 1933 to 1994, including a remarkable 40 consecutive years with a majority in the House of Representatives.

This party had a broad coalition centered on working-class voters. This broad coalition included culturally “conservative,” “moderate,” and “liberal”2 wings, brought together by support for “left-wing” social democracy described earlier, such as the New Deal and Great Society platforms.

In the 21st century, the Democratic Party has a narrower coalition centered on PMC voters. Its “conservative” and “moderate” wings are basically nonexistent. When it wins a majority in Congress, it does so narrowly and for short periods of time. It is the dominant political alignment among the wealthiest Americans. It has, with one brief respite, been losing working-class voters throughout the 21st century.

What happened? The Democratic Party’s constituency got hegemonized.

The Republican Party, on the other hand, has been affected more indirectly.3

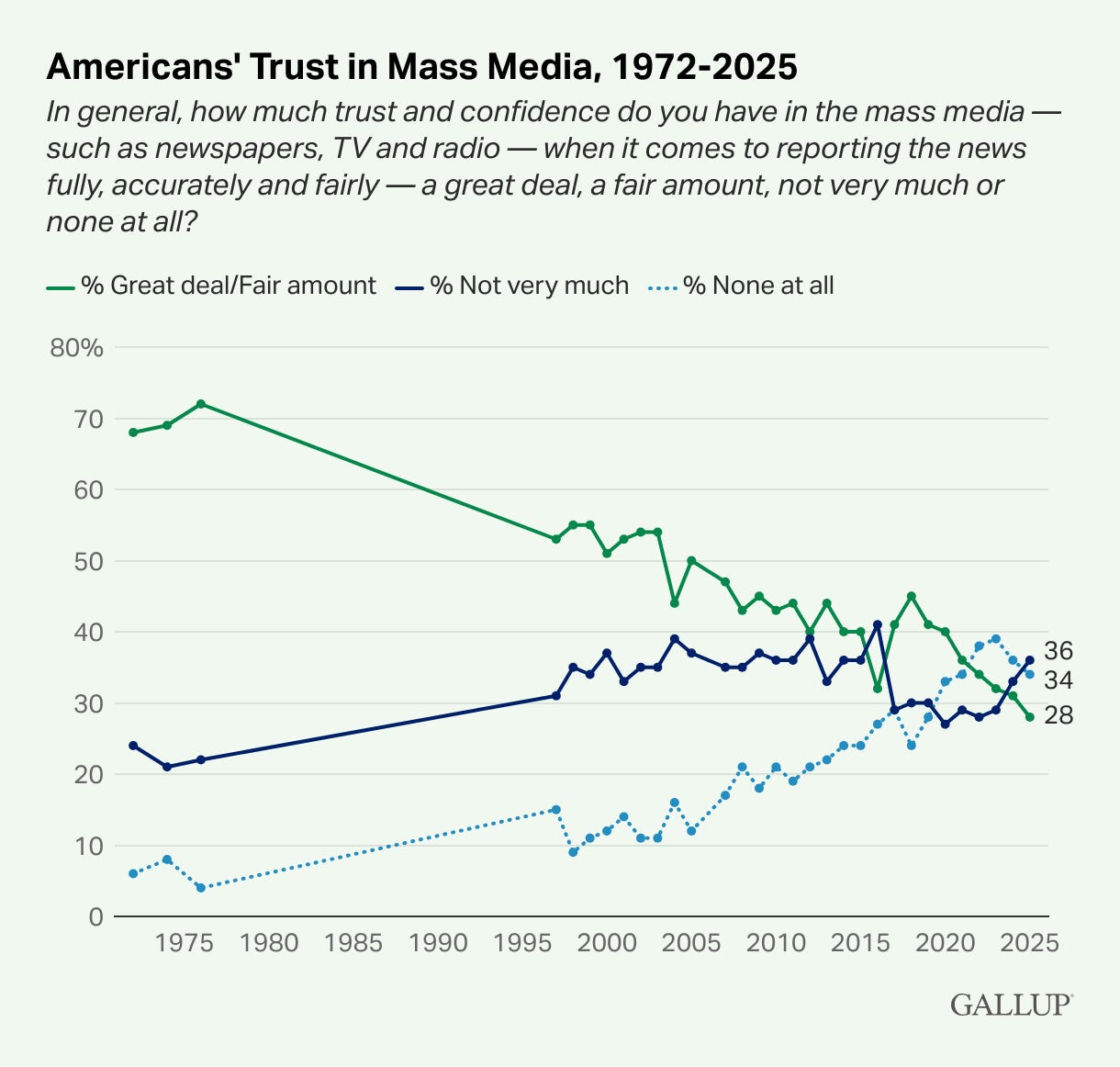

Trust in mass media has declined dramatically since the 1970s.

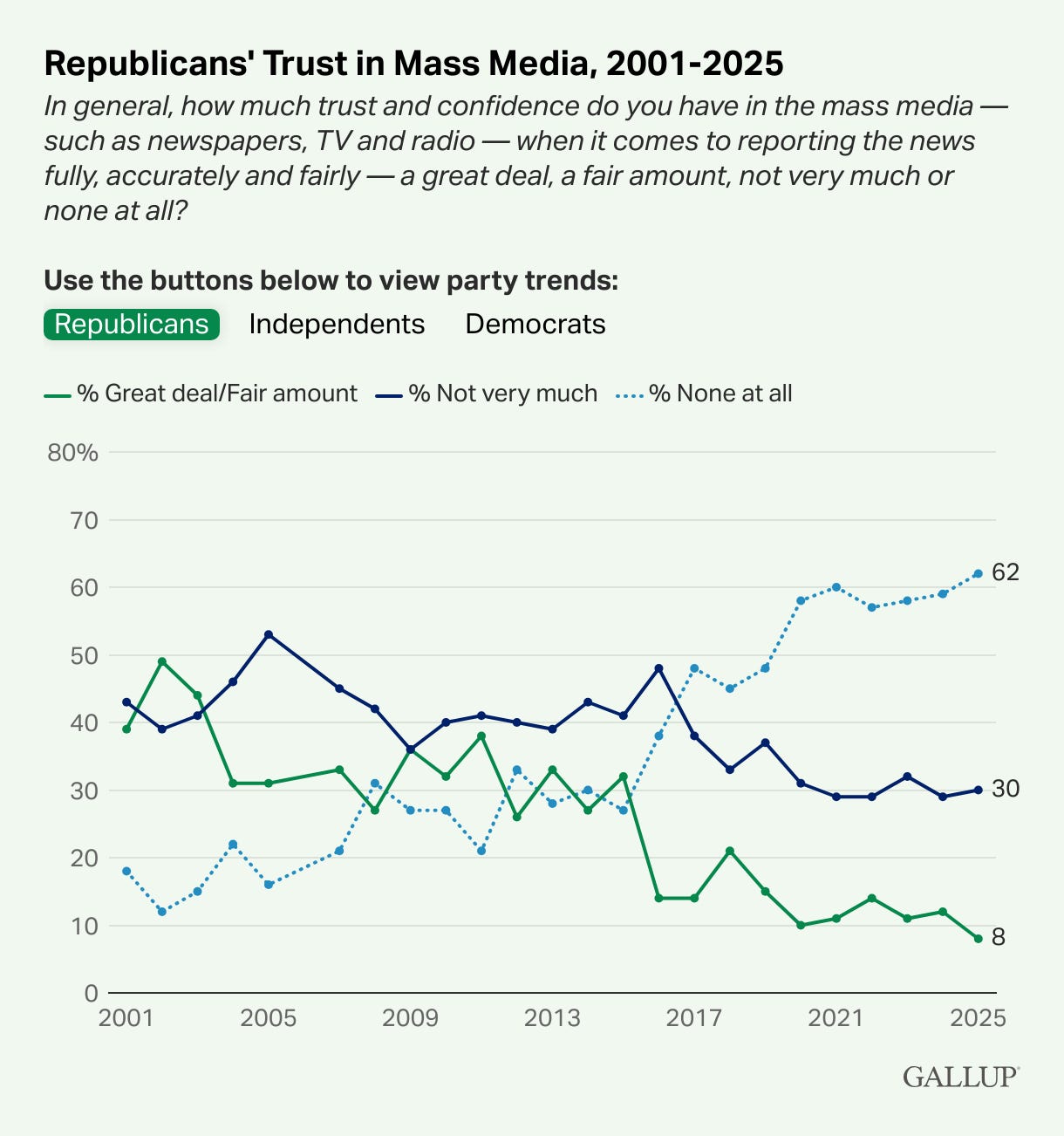

And this decline has particularly affected Republican-leaning voters.

A similar phenomenon has occurred regarding trust in academia: a general decline that is particularly pronounced among Republican-leaning voters.

The decline in trust in the organs of cultural hegemony is, in large part, a logical reaction to their complicity in manipulating common sense.

While Americans—and Republican-leaning voters in particular—might be justified in their distrust of mass media and academia, this does leave a void in information dissemination. The organs of cultural hegemony are also the vehicles that, in a more honest context, would spread knowledge. Into this vacuum of knowledge-spreading institutions, therefore, comes some amount of conspiracy theories, etc.

This creates an environment ripe for capturing by a demagogue, which is precisely what Donald Trump has done with the Republican Party in the past decade. This regime often employs the rhetoric of counter-hegemonic populism, which appeals to many in the 21st-century Republican constituency, but only occasionally acts as a counter-hegemonic force.

Living as a Dissident

In addition to being a tool useful for analyzing the demographics of political realignment, the theory of cultural hegemony serves as a warning for those of us who are dissidents, i.e., those who disagree with the hegemony’s orthodoxy on one or more issues.

All dissidents deal with cultural hegemony, as it operates in part through mass media. However, this is particularly acute for those dissidents who are themselves part of the PMC or for those dissidents who aspire to a life of the mind.

For PMC dissidents, you will constantly encounter people in your life—your coworkers, your neighbors—who are hostile to your views, prejudicially assume you agree with their opinions, do not understand your views, have false and defamatory beliefs about your reasons for having your views, expect their opinions to be enforced in the workplace, and are either unwilling or unable even to have a conversation with you about your disagreement.

This is because the hegemonized adopted their opinions as common sense, in the Gramscian sense. Their opinions are the axiomatic premises—not the conclusions—of their thinking. These opinions were formed by a profound incentive structure prepared for them long before they started their journey up the ladder of college-educated strivers.

For dissidents who aspire to a life of the mind, you are doubly at a disadvantage. We live in an era of elite overproduction, when it is extremely unlikely that any one of us can secure a job in intellectual work.

On top of this, you must contend with a modified version of O’Sullivan’s First Law: any institution not overtly “conservative” or “right-wing” will gradually become more and more hegemonized.

Therefore, if you disagree with self-styled “progressive” opinion on any culture war issue, the faster you accept that you must seek out alternative spaces, the better off you are.

This is not something a young person wants to hear. If elite overproduction has already made it hard to get an intellectual job in academia or “mainstream” media, then trying to target the even smaller number of jobs in “conservative” or “heterodox” spaces looks even worse.

Yet this counsel of realism should not become counsel of despair. Counter-hegemonic spaces exist precisely because others before you made the same calculation and built institutions outside the hegemonized mainstream.

Conclusion

Cultural hegemony in the 21st century explains why the Democratic Party abandoned its working-class coalition for a narrower PMC base, why trust in major institutions has collapsed—particularly among Republican-leaning voters—and why political discourse has become so difficult, especially among the educated who should be capable of reasoned debate.

For dissidents, understanding this dynamic matters less for changing the hegemony than for navigating it. Institutions will not become more open to heterodox views. The incentive structures that produce submission remain intact.

The theory of cultural hegemony is, ultimately, a tool for seeing clearly. It explains why certain views backed by wealth and status dominate society, and why the political landscape has shifted in ways that confuse those using 20th-century analytical frameworks.

The decline in trust in hegemonized institutions—mass media, academia, credentialed expertise—suggests we may be witnessing not the permanent triumph of cultural hegemony, but rather its peak.

Putting Theory to Work

That is enough theory. What empirical analyses does this lead to?

PMC Consolidation — the demographic shift in the Democratic Party from a broad coalition to a narrow, PMC-dominated constituency

“The Big Lurch” — the dramatic change in opinion in the Democratic Party constituency on culture war issues in the 21st century from the 20th century

The Packaging of Opinions — the increase in the probability of having any one opinion promoted by the cultural hegemony, given that you hold any other opinion promoted by the cultural hegemony

The first two analyses are straightforward trend analyses that can be done using data sources such as the General Social Survey and the American National Election Studies.

The third analysis would involve the use of a statistical model. However, the modeling is not the challenging part. The hard part is finding a public use data set that asks each respondent about enough culture war issues and has been done so repeatedly over time. This may not exist, so I will have to see what I can come up with instead.

I doubt that the left-right spectrum has ever been a useful analytical tool. See the thesis of Hyrum and Verlan Lewis in The Myth of Left and Right.

“Liberal” in this context of disposition toward cultural issues has little to nothing to do with the philosophical tradition of liberalism. Indeed, the “Liberal” party in most countries is the “right-wing” or “center-right” party. “Liberal,” when opposed to “conservative” in an American context, is typically a synonym for hegemonized.

In the United States, we elect a president in an effectively single-district, first-past-the-post election (though this is mitigated somewhat by federalism and the electoral college). This leads to a two-party system at the presidential level. Because the election of our presidents has far more influence than it should—both on the electoral landscape and on popular culture—most elections in the United States also become two-party affairs.