How Many Women Quit Birth Control Due to Side Effects?

Millions of women have abandoned contraceptive methods, and the reasons differ dramatically by method.

Much social criticism of the so-called sexual revolution — i.e., the changes in sexual and reproductive culture that followed the 1960s and 1970s — ruminates on what happens when a society suddenly acquires effective contraception.

However, this is the wrong premise.

We are actually living through a time in which a society thinks it has effective contraception, but does not. One of the major goals of my empirical analysis is to correct this mistaken belief.

But before we get into pregnancies conceived during contraceptive use, let us examine a related topic: “modern” contraceptives available today come with side effects — side effects so severe that women oftentimes stop using them.

Measuring Dissatisfaction

The National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG), the preeminent fertility survey in the United States, has asked female respondents ever since its Cycle 6, which was done in 2002, questions such as:

Some people try a method and then don’t use it again, or stop using it, because they are not satisfied with the method. Did you ever stop using a method because you were not satisfied with it in some way?

Then, for select methods, the NSFG asks a follow-up question such as:

What was the reason or reasons you were not satisfied with [method name]?

Together, these give us a picture of how frequently side effects make a contraceptive method unbearable.

Figure 1 gives us a baseline for the prevalence of the most common methods of contraception in the United States. I use the 2015-2019 data set because, as I have written about, there are issues with the 2022-2023 data (and, indeed, survey data more generally after the COVID-19 pandemic).

The numbers from Figure 1 serve as the denominators for the rest of the analysis, and the important takeaway is that the stakes are large. For instance, a one percentage point difference in discontinuation rate for pill-based methods represents about half a million women.

Discontinuation Rates by Method

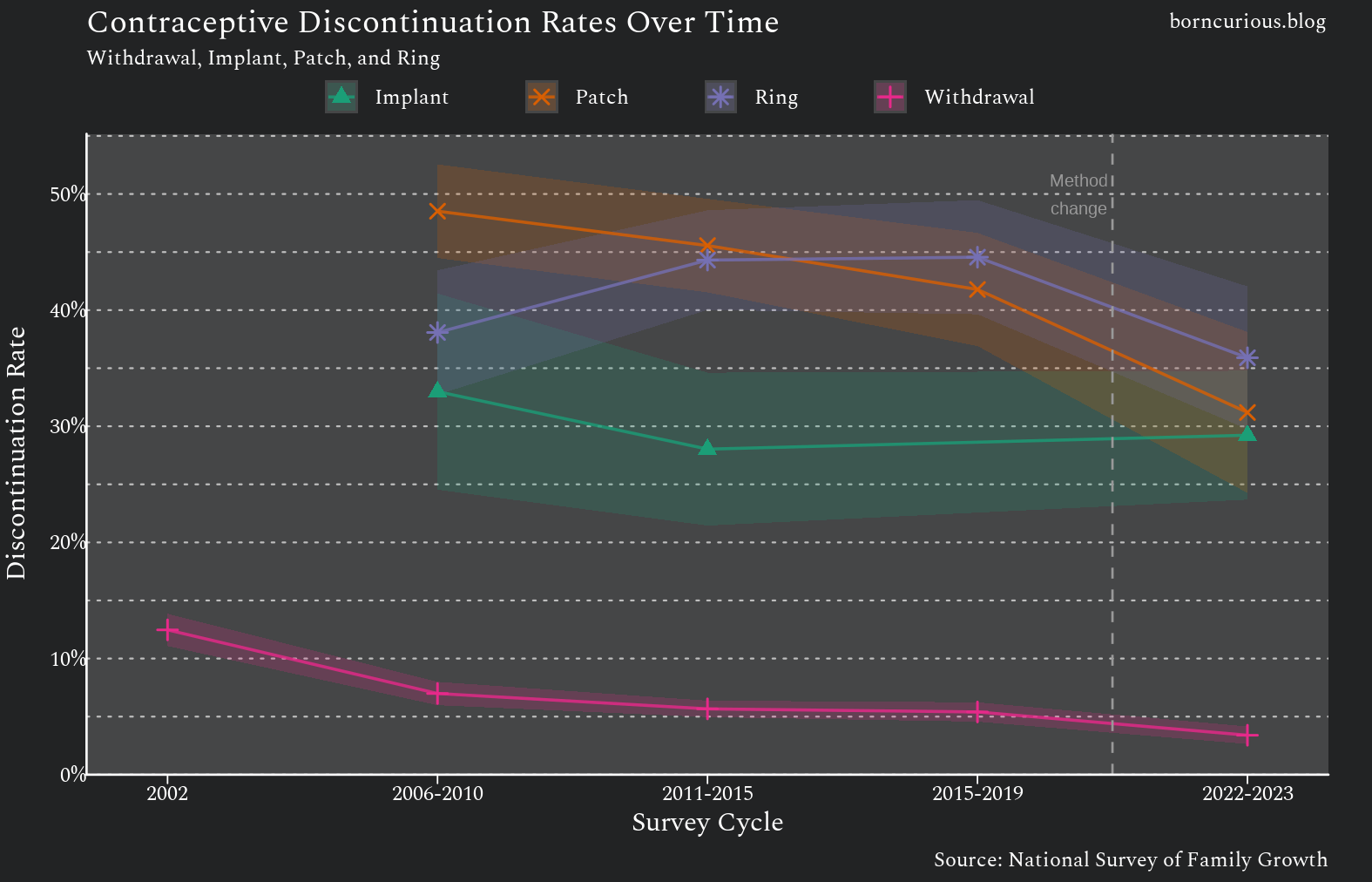

The raw discontinuation rates (which include discontinuations for reasons other than side effects) are mostly consistent over time, except for the 2022-2023 data set. The estimated discontinuation rates all decrease in 2022-2023. However, due to methodological changes for the 2022-2023 NSFG, it should not be compared with earlier data, and the earlier data are generally more reliable.

Generally, there are three tiers of discontinuation rate, in order of lowest to highest:

withdrawal and condom

pill, implant, and intrauterine device (IUD)

patch, ring, and Depo-Provera

Withdrawal

Withdrawal is a natural comparison baseline for contraceptive methods, since it predates all “modern” methods by millennia. The discontinuation rate for withdrawal is in the range of 5% to 13%. (Figure 3) This leads to 2,729,000 (±514,000) total discontinuers based on 2015-2019 data.

Condoms

Condoms have a discontinuation rate similar to that of withdrawal. (Figure 3) However, because more people have tried condoms than any other method, this low rate still represents a lot of women in total terms. There were 5,102,000 (± 783,000) women who discontinued condom use due to dissatisfaction, according to 2015-2019 data.

Hormonal Methods

All the remaining methods (with one major exception) are essentially the same method in different modalities: exogenous hormones. They all involve different ways of delivering a cocktail of progestins and estrogens.

Pill

The discontinuation rate for pill methods hovers around 30% to 35%. (Figure 3) Pills are the most popular method after condoms. With their higher discontinuation rate, 17,910,000 (± 1,760,000) women have discontinued them due to dissatisfaction, based on 2015-2019 data.

To put that in perspective, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, there were only 74,394,051 women of reproductive age in the United States eligible for the 2015-2019 NSFG. About a quarter of women in the United States have quit the pill due to dissatisfaction!

There are over a hundred and fifty different brand names of contraceptive pills available in the United States. Even though some are basically the same as others, and some are in practice not manufactured, there are still dozens of discrete formulations of oral contraceptives.

Implant (Nexplanon)

In contrast, there has basically been one implant-based contraceptive available at a time in the United States. Norplant had Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval starting in 1990, but was withdrawn in the United States in 2002 amid massive litigation. Implanon was introduced in the United States in 2006, but was discontinued in 2012. Nexplanon started replacing Implanon in 2010, and is the only implant-based contraceptive currently available in the United States.

Implants have a discontinuation rate right around ~30%, similar to contraceptive pills. (Figure 3) The 2015-2019 NSFG did not ask about implants, leaving a data gap because implant use has increased substantially in recent decades. According to the 2022-2023 data, 1,727,000 (± 406,000) women have discontinued implants due to dissatisfaction.

IUD

The discontinuation rate for intrauterine devices (IUDs) appears to be the least consistent based on NSFG data. (Figure 3) However, several things explain this. The NSFG changed its handling of IUDs midway through the run of the discontinuation questions, separating copper IUDs from hormonal IUDs.

Furthermore, the IUD market in the United States was effectively destroyed by the Dalkon Shield scandal of the 1970s. It did not recover until the 2000s — right when the NSFG began asking these questions. The small number of IUD users in early survey cycles, combined with a rapidly changing user population as the method regained acceptance, makes for noisy estimates.

Broadly speaking, IUD discontinuation rates stabilized in the same tier as pill methods, hovering around 25% to 35%.

Injectable (Depo-Provera)

Methods in the high-discontinuation tier — Depo-Provera, patch, and ring — tend to have rates of discontinuation due to dissatisfaction in the 40% to 50% range. (Figures 2 and 3) However, patch and ring methods are less common than other methods.

Depo-Provera is notable both for being the only injectable contraceptive method available in the United States and for having a very high discontinuation rate. Around 7,382,000 (± 824,000) women have discontinued Depo-Provera due to dissatisfaction. Additionally, there is active litigation over allegations that Depo-Provera increases the risk for brain tumors.

Side Effects Prevalence

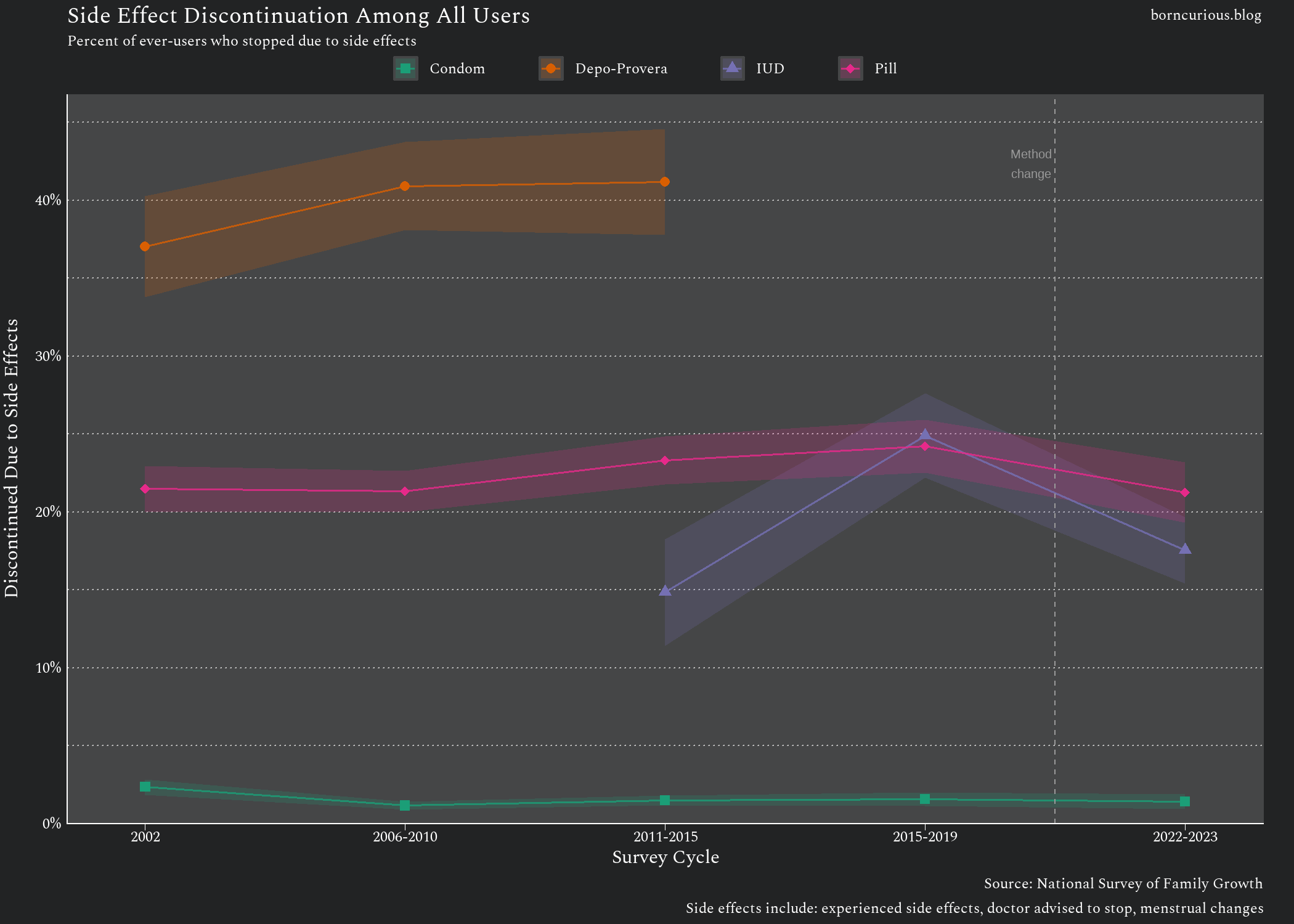

The gap between the low-discontinuation-rate tier of methods and the two higher-discontinuation-rate tiers widens when we look at why women discontinue due to dissatisfaction.

Looking at the answers to follow-up questions asking the reason for discontinuation of condoms, most discontinue either because of the effects on the pleasure felt by the respondent or her partner. (Figure 4)

Looking at the answers for the pill, by comparison, the reasons cited for discontinuation are overwhelmingly side effects. (Figure 5)

This allows us to calculate a discontinuation rate due to side effects for the four methods that have follow-up questions in the NSFG asking about reasons. For these purposes, I took “you had side effects,” “did not like menstrual cycle changes,” and “doctor told you not to use” as discontinuation due to side effects.

Discontinuation rate due to side effects for condoms is consistently less than 2.5%. For pills, it is in the 20% to 25% range, and for Depo-Provera, it is around 40%. (Figure 6)

This leads naturally to the question, what exactly are these side effects?

What Are the Side Effects?

This is easy enough to look up because official FDA-approved documentation must list the adverse effects of a drug. The prevalence of side-effects in the documentation tends to be underestimated because the estimates come from clinical trials, which overstate drug efficacy and underestimate side-effects — a topic worthy of another article of its own.

Nonetheless, the FDA documentation at least gives a list of what the side effects are.

Figure 7 comes from the tables on the official Depo-Provera label. “Amenorrhea” refers to the absence of regular menstruation. The percentages are the number of women with each adverse reaction, expressed as a proportion of the total number participating in the clinical trial.

As discussed above, while there is one injectable (Depo-Provera) and one implant (Nexplanon), there are many different brands of oral contraceptive pills. I just pulled the label for one of them to get a list of side effects in Figure 8, so the incidence percentages shouldn’t be overinterpreted. “Menorrhagia” refers to abnormally heavy or prolonged menstrual bleeding, and “dysmenorrhea” refers to painful menstruation.

Generally, the side effects of hormonal contraception include absence of menstruation, excessive bleeding during menstruation, headache, abdominal pain and cramping, nausea, weight gain, acne, dizziness, and loss of sexual desire.

Conclusion

Data from the National Survey of Family Growth reveal that contraceptive discontinuation due to dissatisfaction is widespread, particularly for hormonal methods.

Discontinuation rates fall into three tiers: withdrawal and condoms cluster around 5–13%, hormonal pills, implants, and IUDs hover between 25–35%, and high-discontinuation methods like Depo-Provera, the patch, and the ring reach 40–50%.

The reasons for discontinuation differ dramatically by method type. Women who stop using condoms cite effects on sexual pleasure; women who stop using hormonal methods overwhelmingly cite side effects.

This is the second in a series of empirical analyses that scrutinize the culture that emerged from the sexual revolution. The previous was “Intercourse Is Remarkably Bad at Making Women Orgasm.” Upcoming analyses will investigate the increase in the incidence of unintended pregnancies after the sexual revolution and estimate the rates at which contraceptive methods fail in real life.