Black Newborns Do Not Have a Better Chance of Survival with Black Physicians

A follow-up study identifies a critical flaw that overturns the conclusion of the original study, which the popular culture was misrepresenting anyway.

Introduction

In her dissenting opinion on Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson wrote,

Beyond campus, the diversity that [the University of North Carolina] pursues for the betterment of its students and society is not a trendy slogan. It saves lives. For marginalized communities in North Carolina, it is critically important that UNC and other area institutions produce highly educated professionals of color.… For high-risk Black newborns, having a Black physician more than doubles the likelihood that the baby will live, and not die.

The claim that Black newborns treated by a Black physician have double the likelihood of living was based on a paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. (Greenwood et al., 2020)

The claim is false, for at least two reasons.

Greenwood et al. were mistaken because the researchers failed to adjust their model for the most important confounding variable in newborn mortality: whether or not a newborn has a very low birth weight. Borjas & VerBruggen (2024) detailed this in a follow-up paper also published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Justice Jackson completely overstated what Greenwood et al. found. Newborn mortality is, mercifully, a rare event. Greenwood et al. concluded (falsely) that the probability of this rare event (death of a newborn admitted to a hospital) was lower for Black babies treated by Black physicians than for Black babies treated by White physicians. They never concluded that Black babies admitted to a hospital and treated by Black physicians have fully double the survival rate of those treated by White physicians.

Therefore, this case offers two lessons, one for researchers and one for anyone who reports on scientific findings.

Background for the Original Study

Greenwood et al. retrieved data from the State of Florida’s Agency for Healthcare Administration (AHCA). This AHCA data set contains a record of every patient admitted to a hospital in Florida, and so this data set has been used for prior research in public health and economics.

The researchers used data from 1992 to 2015. They ended in 2015 because, in the fourth quarter of 2015, the data set started using a new version of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD). They began in 1992 because the AHCA data set started recording the racial categorization of patients in 1992.

However, the AHCA data set does not record the race of the attending physician. Remarkably, the researchers manually searched the Internet for the physicians in the data set, found publicly available pictures of them, and created their own data set of physician racial categorization.

Once they joined these two data sets together, they fitted a series of regression models.

Regression Model Analysis

Note: If you are already familiar with the concepts of regression models, interaction terms, and confounding variables, please skip ahead to “Results of the Original Study” below.

A regression model is a statistical method to quantify the association between one variable — the response variable — and one or more explanatory variables.

A very simple regression model might be

where y is the response variable and x is an explanatory variable.1

For instance, the y response variable could be the average weight of a person, and the x explanatory variable could be the height of a person.

To fit this regression model to real-world data, a procedure would be used that would — among other things — give a value for β.2 Generally, taller people are, on average, heavier, so the two variables would be positively associated and the value for β would be positive.

Once armed with a value for β, we could find the average weight for people of a given height by plugging in a value for x, multiplying it by the value the model gives us for β, and calculating a value for y.

That is not all that fitting a regression model would tell us. Fitting the model would tell us whether the response variable and explanatory variable(s) are associated at all. If they are, it would tell us how much of the variation in the response variable is explained by the explanatory variable(s).

Because of this, regression models are very common in academic research.

Categorical Variables

A person’s height takes on values like “5.25 feet” or “6.1 feet” which are continuous quantities because they can be any number within a range. However, regression models can also handle categorical variables, such as “is an apple” or “is an orange.”

The way that this is typically handled is to use an explanatory variable x that takes on the value 1 for one of the categories and 0 otherwise. Let us consider an example regression model where y represents the average weight of a piece of fruit.

For this model to represent whether a given individual is an apple or an orange, we would pick one of the categories — for example, apple — to be represented by x. The value of x would then be 1 for apple and 0 for orange.

Fitting the regression model to the data still results in values for the beta terms as before, and so gives estimates for the average value of y for the different categories.

The average weight of an apple would be β1 + β0 because

and the average weight of an orange would be β0 because

Interaction Terms

It is rare to see a regression model in actual use that has just a single explanatory variable.

For instance, let us consider a model for testing an infertility treatment in a given population where y represents a rating of fecundity (how able you are to reproduce).3 Let x1 be 1 if a person is a woman and 0 if a person is a man. Let x2 be 1 if a person received the treatment and 0 otherwise.

With this encoding, whether β2 is positive or not would tell us whether the fertility treatment works. A positive β2 value means that those who received the treatment have on average a higher fecundity than those who did not.

Whether β1 is positive or not would tell us whether women or men have more of an infertility problem in this population. A positive β1 value means that women have on average higher fecundity than men, and a negative β1 value means that men have on average higher fecundity than women.

What if the infertility treatment only works for women or for men, but not both?

For models that have two or more variables, these sorts of questions can be answered by including an interaction term in the model.

In cases where either x1 is zero (when a person is a man) or x2 is zero (when a person did not receive the fertility treatment), the β1,2x1x2 term drops out of the calculation of y. Thus, a nonzero β1,2 is an extra addition or subtraction only when a person is both female and received the fertility treatment.

The value for β1,2 tells you if there is an interaction between the fertility treatment and a person’s sex. If β1,2 is nonzero, then it tells you that the fertility treatment has a different effect for women than for men.

Confounding Variables

When dealing with observational data, it is important to adjust a regression model for potential confounding variables by including them in the model.

Suppose that Jill is doing a study of what makes people happy in her community. Jill is a cat owner and gets joy out of her relationship with her cat, so she fits a simple regression model to survey data.

where y is a happiness score and x1 is 1 if someone owns a cat, 0 otherwise.

Much to her surprise, Jill finds that the β1 from fitting the model is negative. People who own cats are actually less happy than the general population on average.

Is there something about owning a cat that makes people unhappy? This assumes an association between the two variables like that depicted below.

However, it might not be the case that cat ownership makes people unhappy. Instead, a situation like that depicted below might be going on.

Confounding occurs when two variables appear to be associated, but they are not, because a third confounding variable is associated with both of the variables independently.

In an experimental setting, you can control for confounding variables with random assignment of test subjects between experimental and control groups. In observational studies, though, you have no such ability. With observational data, you must adjust for confounding variables in your model.

For instance, in Jill’s scenario, it turns out there is a large research university in her community. It also turns out that a lot of graduate students and postdoctoral fellows at this university own cats — at a substantially higher rate than the general population.

Grad students and postdocs also are more likely to be unmarried, to have little free time, and to be in worse economic health than their peers — all things that have been associated with unhappiness in various populations.

Jill fits a second model, this time adjusting for this potential confounder.

where y and x1 are as before and x2 is 1 if a person is a grad student or postdoc, 0 otherwise.

Fitting this second model leads to a β1 that is statistically indistinguishable from zero. This is still not the result Jill was hoping for; it turns out that whether or not someone has a cat is a poor predictor of happiness. At least having a cat doesn’t make you less happy.

The fitting also leads to a negative β2 value. Jill has stumbled onto the conclusion that grad students and postdocs are on average less happy than the rest of the community.

The results of fitting the second model confirm that x2 is confounding x1. The negative association between x2 and y appeared to be a negative association between x1 and y in the original model because the original model did not include x2. Simply including x2 in the model fixes this.

With experiments, the random assignment of subjects between test and control groups handles all confounding variables automatically. However, with observational data, you have to include all the confounding variables in the model. Therefore, dealing with confounders in observational data is more challenging. If you do not think of all the confounding variables and include them in your model, your results will be confounded.

Results of the Original Study

Greenwood et al. fitted a series of regression models with a response variable that encoded whether a newborn died and two main explanatory variables: a variable for whether or not the newborn was Black or White, and a variable for whether or not the attending physician was Black or White.

To make things simpler for their manual categorization of the race of the physician, the researchers only included individuals categorized as “Black” or “White” throughout their analysis.

All of the models included an interaction term for the two main explanatory variables for when both the patient and physician are Black. This interaction is the basis for the results of the paper and what Greenwood et al. call a “racial concordance effect.”

To their credit, Greenwood et al. did try to adjust for confounding variables. They fitted several models, each with more variables included to adjust for potential confounders. These potential confounding variables included insurance status, time, hospital, and specific physician.

The most obvious potential confounding variables when survival is the outcome are whether or not a baby has any disease conditions. To address this, Greenwood et al. adjusted their models with 65 variables, each encoding whether or not the newborn had one of the 65 most common ICD disease codes.

Greenwood et al. observed that there was a higher rate of newborn mortality among Black newborns than among White in Florida hospitals from 1992 to 2015.

In the sample, the raw mortality rate is 289 per 100,000 births among the 1.35 million White newborns and is 784 per 100,000 births among the 0.46 million Black newborns.

This is a disparity of 495 deaths per 100,000 births. The researchers’ most fully specified model estimates a beta value for the Black newborn encoding variable that indicates a value of about 311 excess deaths per 100,000 births. Thus, they attribute about 495 − 311 = 184 deaths per 100,000 births to confounding variables that their model adjusts for.

Their estimate of the beta value for the interaction term encoding the racial concordance effect is −129 deaths per 100,000 births. Thus, they estimate if Black newborns all had Black physicians, the racial concordance effect could reduce these excess 311 deaths per 100,000 to 182 deaths per 100,000, all other things being equal.

This would be a ~52% reduction in the disparity, which would be a substantial effect if it were true.

The authors themselves noted that the decline in the estimate of the beta for the interaction term in each subsequent model was evidence that there was confounding:

Attenuation of the concordance-coefficient as additional controls are added to the model indicates that these observables are correlated with both concordance and mortality outcomes. Thus, it is plausible that the models with fewer controls suffer from an omitted-variable bias.

“Omitted-variable bias” is what the authors are calling the effects of missing confounding variables.

The authors ran some heuristics to check if they might have missed an important confounding variable altogether, which led them to this caution:

This underscores the need for controls, which are chosen deliberately as strong predictors, and also indicates that caution regarding the persistence of omitted variable bias is warranted.

It turns out, their caution was correct and their results incorrect. There were some other issues,4 but confounding was the main flaw that led to the results of the study being incorrect.

Misrepresentation of the Original Study

Before we get to the follow-up study that illustrated the confounding variables that Greenwood et al. missed, let us consider the assertion of Justice Jackson.

For high-risk Black newborns, having a Black physician more than doubles the likelihood that the baby will live, and not die.

This was taken almost verbatim from an amicus brief by Heather Alarcon and Frank Trinity on behalf of the Association of Medical Colleges, who wrote,

And for high-risk Black newborns, having a Black physician is tantamount to a miracle drug: it more than doubles the likelihood that the baby will live.

Scope of Inference

First, this assertion ignores the scope of inference of the original paper. The sample is a census of infants born in Florida hospitals from 1992 to 2015. The scope of inference is exactly this population. It does not apply to all newborns everywhere for all of time. For instance, things may have changed since 2015.

Furthermore, the State of Florida is not representative of every state in the United States, let alone everywhere in the world. Some hospital outcomes might be better in Florida than in other places; others might be worse.

Indeed, Greenwood et al. did not specifically study “high-risk” newborns. It is not clear where Alarcon and Trinity got that.

It takes just eight words to fix the scope of the original assertion by including “born in Florida hospitals from 1992 to 2015.” This is a reminder for everyone reporting scientific results to spend the few words it takes to report the scope of inference of the results.

Double the Survival Rate Makes No Sense

The raw survival rate of Black newborns born in Florida hospitals from 1992 to 2015 is 99.216%.

Even if all the deaths of Black newborns occurred under the care of a White physician, the survival rate for Black newborns with White physicians would not be much lower, because newborn death is, thankfully, a rare event. Suppose it were 98%. The survival rate among Black newborns treated by Black physicians if such an arrangement “doubles the likelihood that the baby will live, and not die” would be 196%. But survival rates can never be greater than 100%.

As they later informed the Court through counsel, Alarcon and Trinity saw how Greenwood et al. reported a 58% reduction in the newborn mortality disparity when Black newborns were treated by Black physicians, and in an act of innumeracy, thought that halving the mortality rate was equivalent to doubling the survival rate. It is not.

Even after this admission, Alarcon and Trinity are still wrong. Greenwood et al. did not even report a halving of the mortality rate for Black newborns when cared for by a Black physician. The 58% reduction was in the disparity of the mortality rates between White and Black newborns.

Taking the White newborn mortality rate as a baseline, there were 289 deaths per 100,000 births. The adjusted disparity estimated by Greenwood et al. was 311 deaths per 100,000 births. This leads to an adjusted Black newborn mortality rate of 600 deaths per 100,000 births. With the estimate of the racial concordance effect from Greenwood et al., this could be lowered to 471 deaths per 100,000 births if all Black newborns were cared for by Black physicians.

This would be a 24% reduction in the mortality rate. This is still substantial, but also substantially less than a 58% reduction in mortality rate.

Thus, Alarcon and Trinity’s reporting of Greenwood et al. was wrong through and through. Greenwood et al. estimated a potential reduction in mortality rate from 0.60% to 0.47%.

The Follow-up Study

However mistaken the reporting on the original paper by Greenwood et al. (2020) in the popular culture was, the bigger issue is that the results of the analysis itself were incorrect.

Borjas & VerBruggen (2024) report that Greenwood et al. did not adjust for important disease conditions that can lead to death. As described above, Greenwood et al. did adjust for the 65 most common ICD disease codes. Why was that not enough?

The issue is that Greenwood et al. adjusted for the most common ICD codes, and newborn death is uncommon. Thus, they adjusted for conditions that did not pose much risk of death. Indeed, some of the ICD codes that Greenwood et al. adjusted for weren’t even a disease condition. Borjas & VerBruggen report,

…the most common “comorbidity” is “Single liveborn, born in hospital, delivered without mention of cesarean section” (ICD-9 code V30.00), present for two-thirds of the sample.

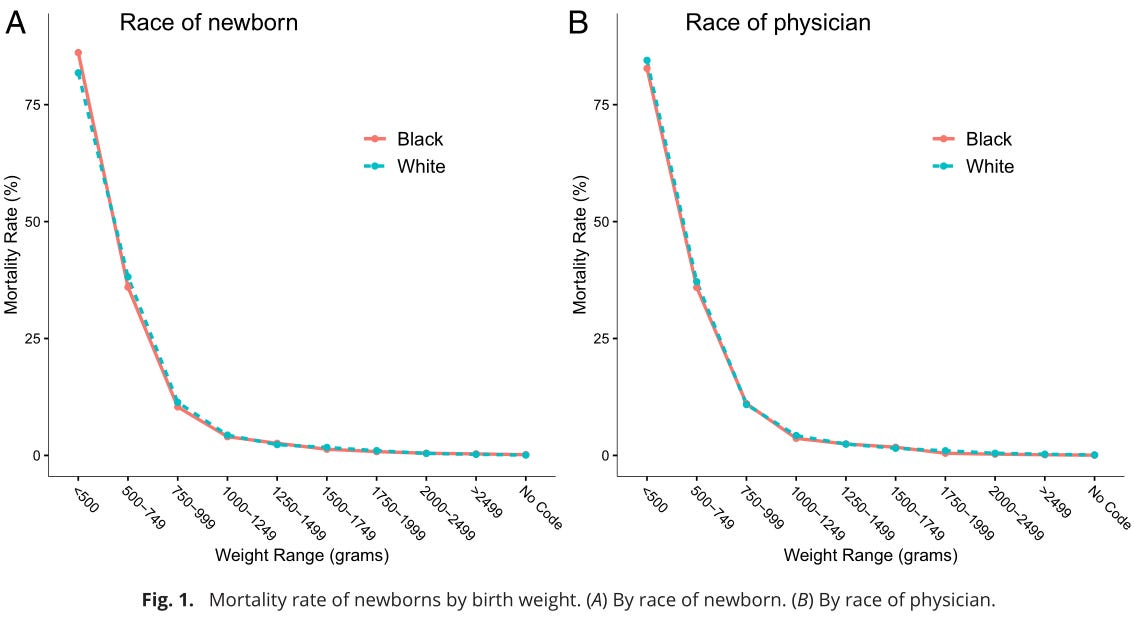

What Greenwood et al. should have done was adjust for ICD codes that are associated with a risk of death. Borjas & VerBruggen found that a single factor was very predictive of the risk of death among newborns, that is, having a birth weight below 1,500 grams, which they call “very low” birth weights.

Such “very low” weights are an important predictor of mortality. In 2007, only 1.2 percent of White newborns and 3.3 percent of Black newborns had weights in this range; but these newborns accounted for 66 percent of neonatal mortality among White babies and 81 percent among Black babies.

This is a very stark fact when plotted on a graph with mortality rate on the y-axis and birth weight on the x-axis, as Borjas & VerBruggen did in Figure 1 in their paper.

When the regression models of Greenwood et al. are amended to adjust for the very low birth weight disease codes, the estimate for the beta of the interaction term is no longer statistically different from zero. The racial concordance effect goes away.

How did this confounding occur? For whatever reason, Black newborns with healthy birth weights tend to get paired more frequently with Black physicians, and the proportion of Black newborns seen by White physicians who have very low birth weights is greater than the proportion among those seen by Black physicians. Borjas & VerBruggen summarize this in Figure 2 from their paper.

This was a subtle mistake. Greenwood et al. did try to adjust for confounding variables. They just chose the wrong variables to adjust for.

This is a reminder that when selecting potential confounding variables to adjust for, we should look for confounding variables associated with the response variable of the model. In this case, the response variable was the probability of the death of a newborn. The ICD codes that should have been used were ones associated with newborn mortality.

Conclusion

There are lessons to be learned from this on how to report on scientific results and how to do data analysis for scientific results. For the former, it is important to understand the scope of inference of the result and to have enough numerical literacy to report the result accurately. For the latter, it is important to adjust models for potential confounding variables and to pick variables associated with the response variables of the models.

There is also an important lesson to be learned about how to prevent the deaths of newborns. If you read just the original paper by Greenwood et al., then you might support attempts to segregate neonatal care wards. This would not have worked. No newborns would have been saved, and scarce resources might have been allocated to an approach that would not work — resources that could have been spent on approaches that could actually save babies’ lives, such as interventions that prevent very low birth weights.

This misguided attempt at knowledge generation vividly captures a flaw in the spirit of the times.

…of the 9,992 physicians in the original sample, pictures could only be found for 8,045, and our analysis omits physicians missing a photo.

We can imagine Greenwood et al. hunched over their computers for hours on end, looking at over eight thousand photographs.

We can imagine a tired-eyed graduate student or postdoctoral fellow calling over a buddy after finding a photograph for the thousandth time.

“Does this doctor look like a Black man or a White man?”

“Hmmm, he looks Indian, actually. Well, South Asian, at least.”

Over and over again, this scene plays out with the sincere and well-intentioned hope that if we focus on people’s race some more, then Black babies will be saved from premature death in the future.

Ultimately, the hours spent classifying doctors by race did not help anyone save Black babies. On the contrary, it led to a false belief that — for four years, anyway — may have led people to adopt policies that do Black newborns no good.

As it turns out, what actually could save more Black newborns are… the things that save newborns. Looking at anyone’s skin color doesn’t help.5

I do not want to censure Greenwood et al. in particular.6 Rather, Greenwood et al. are products of their social context. The trend among what Musa al-Gharbi would call the “symbolic capitalists” of the United States is to think that if we could just be “race-conscious” enough we could improve outcomes for Black babies (and similarly for a long list of other groups).

We have a whole slew of researchers, teachers, administrators, journalists, publishers, legislators, lawyers, and judges who are — metaphorically — sitting alongside Greenwood et al., hunched over their computers looking at photographs of doctors and trying to categorize them by race, with the belief that if they just categorize by race hard enough, good things will happen. In this case, at least, that belief is mistaken.

Further Reading

“Justice Jackson’s Incredible Statistic” by Ted Frank — an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal that highlighted the issues in the way the Greenwood et al. results were reported.

“White Doctors Kill Black Babies: Dubious Science and Anti-Racist Medicine” by Jake Mackey and Dave Gilbert — an article in the Unsafe Science Substack newsletter that details how widely adopted the original Greenwood et al. paper is.

“Do Black Newborns Fare Better with Black Doctors?” by George J. Borjas and Robert VerBruggen — an article intended for a popular audience by the authors of the second research paper.

References

Borjas, G. J., & VerBruggen, R. (2024). Physician-patient racial concordance and newborn mortality. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 121(39), e2409264121. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2409264121

Greenwood, B. N., Hardeman, R. R., Huang, L., & Sojourner, A. (2020). Physician-patient racial concordance and disparities in birthing mortality for newborns. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(35), 21194–21200. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1913405117

Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College, 600 U.S. ___ (2023) https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/600/20-1199/

In reality, even in this simplest case, the model would look more like

and fitting the model would give values for all the Greek letters in the model’s formula, but this is beyond the scope needed for the discussion in this article.

"β” is the Greek letter beta.

Technically, “fertility” refers to actual reproduction, such as the number of children a couple has, and “fecundity” refers to the ability to reproduce, even if you haven’t actually had any children.

The other issues reveal the researchers’ lack of statistical sophistication but aren’t relevant to the main flaws of the study, so I have relegated their discussion to this footnote.

The response variable for Greenwood et al.’s models was

yijt … a dichotomous variable indicating whether or not infant-i born under the care of physician-j in quarter-t expires. y equals zero if the infant survives and 100 if the infant expires.

When the response variable of a regression model is dichotomous, you should use logistic regression. Greenwood et al. seem to know this, writing

The estimator is an ordinary least squares (OLS) to avoid interpretation issues associated with nonlinear estimators like logit regression (35).

I looked up the paper cited under reference 35, “The use of logit and probit models in strategic management research” by Glenn Hoetker in the Strategic Management Journal. It gives advice on how to interpret logistic regression models. It does not say to avoid using logistic regression models.

Greenwood et al. are clearly trying to model the risk of death as a probability, which is why they are using zero for infant survival and 100 for infant death. However, with ordinary least squares regression, there is nothing to guarantee that estimates of the response variable y will be between 0 and 100. This is exactly what logistic regression is used for. If you want to model a probability, use logistic regression.

I am not sure what “interpretation issues” with logistic regression Greenwood et al. are alluding to. I did a whole presentation in graduate school on how to interpret results from logistic regression. Many of the tips I gave are the same tips that Glenn Hoetker gives in his paper. You can interpret logistic regression just fine.

Finally, this is a bit of a nitpick, but logistic regression isn’t considered a “nonlinear” model in statistics. It is still a generalized linear model because “linear” models in statistics are those that are linear in the beta parameters. (There is such as thing as nonlinear regression. I did nonlinear regression for a project assignment in graduate school. It is more challenging because there is no guarantee of convergence, but that is not an issue with logistic regression, which is a generalized linear regression.)

Indeed, looking at skin color doesn’t even particularly help with diagnosis. While Black newborns do suffer a greater rate of very low birth weight than White newborns, it is still a low rate of 3.3%. Thus, if a medical professional saw the color of an expectant mother’s skin and started worrying about very low birth weight because of skin color, I could see this coming off as prejudicial and offensive. When in utero, why not just look for actual physiological indicators of risk of very low birth weight? Of course, after birth, you would just weigh the baby.

In a recent interview, George Borgas described his experience with Greenwood et al. When Borgas and VerBruggen got in touch with the authors of the original paper, Greenwood et al. did not respond defensively. Rather, they agreed that Borgas & VerBruggen had valid points, provided their custom-made data set of physician racial categorization to Borgas & VerBruggen, and encouraged Borgas & VerBruggen to publish a follow-up paper in the same journal.

This is the behavior expected of professional scholars, but unfortunately, not all responses are of this level of professionalism, so I wanted to take a moment to commend this behavior. This is how the honest pursuit of knowledge is supposed to work.

I must say "double the survival rate" is a particularly hilarious error - that would mean a rate of survival of more than 100%.

Thanks for this analysis. Seems to me that the most obvious cause of low birth weight is prematurity, and white doctors could be more likely to work in specialist prematurity wards for some reason that wasn't considered in the original study.

It could also be the case that black women are more likely to deliver premature or low weight babies for either genetic, nutritional or social reasons. Blaming everything on systemic racism makes it harder to actually resolve racial differences based on other factors. For example, vitamin D deficiency in colder climates.