Abortion Advocacy is Conservative

To advocate for abortion is to preserve a status quo that has existed for millennia.

Introduction

In the late 20th century and early 21st century in the United States, there has been a binary partisanship divided between left-wing and right-wing in which the right-wing is often labeled “conservative,” and opposition to abortion1 is often associated with the right-wing. This might lead an indolent mind to think offhandedly that opposition to abortion is conservative in a broader sense.

However, political partisanship is rarely logically coherent. Instead, it represents the ephemeral and arbitrary fads of the time and place in which one happens to live. What is right-wing one generation might be left-wing for another generation, and what is left-wing in one place might be right-wing in another place. Just because words such as “conservative” can be used to describe these fads, such labels do not give true insight into historical context.

This article contends that approval of abortion as a method of fertility control is a conservative viewpoint when evaluated according to such dictionary definitions of “conservative” as tending or disposed to maintain existing views, conditions, or institutions. (“Conservative” 2023, 2a)

Abortion is Ancient

Abortion in Greco-Roman Society

The ancient Greek2 physician Hippocrates who lived during the classical period (5th to 4th centuries B.C.E.) wrote of a story in his treatise On the Nature of the Child:

A female relative of mine once owned a very valuable singing girl who had relations with men, but who was not to become pregnant lest she lose her value. The singing girl had heard what women say to one another, that when a woman is about to conceive, the seed does not run out of her, but remains inside. She understood what she heard and always paid attention, and when she one time noticed that the seed did not run out of her, she told her mistress, and the case came to me. When I heard (sc. what had happened), I told her to spring up and down so as to kick her heels against her buttocks, and when she had sprung for the seventh time, the seed ran out on to the ground with a noise, and the girl on seeing it gazed at it and was amazed.

How it looked I will recount: it was as if someone had removed the external shell of a raw egg, and the fluid part inside was visible through the internal membrane. Its appearance was somewhat as follows, to say as much as is needed: it was red and roundish; broad, white strands were seen to be present inside the membrane, pressed together with thick, red serum, and around the membrane on the outside there was bloody material. Through the middle of the membrane something narrow came out, which appeared to me to be an umbilical cord, and through this the movement of breath in and out first took place. From this the membrane spread out and completely enclosed the seed. (Hippocrates 2012, 36–37)

The casual way in which Hippocrates relates the killing of a human embryo in order to preserve the value of a slave is indicative of how little compunction he felt at abortion for the most pecuniary of motives. It also shows that knowledge of how to induce abortion was being promulgated as early as the Greek classical period.

Indeed, abortion was common knowledge throughout the Greco-Roman era. The seminal De Materia Medica of 1st century C.E. pharmacologist-botanist Dioscorides, which was widely read for more than a millennium, notes 66 substances that can be used as an abortifacient.3 (Dioscorides 2000) Soranus, writing in the 1st or 2nd century C.E., describes procedures for inducing abortion in his Gynecology, including some procedures that use substances described by Dioscorides. (Soranus 1991, 66–68) Given its prevalence in widely promulgated texts of the Greco-Roman era, knowledge of how to induce abortion of pregnancy was relatively accessible.

It is clear that the ancients knew of ways to kill embryos and fetuses in utero. It is more difficult to glean what were ancient attitudes toward abortion, however, since there were no nationally representative opinion polls in antiquity.

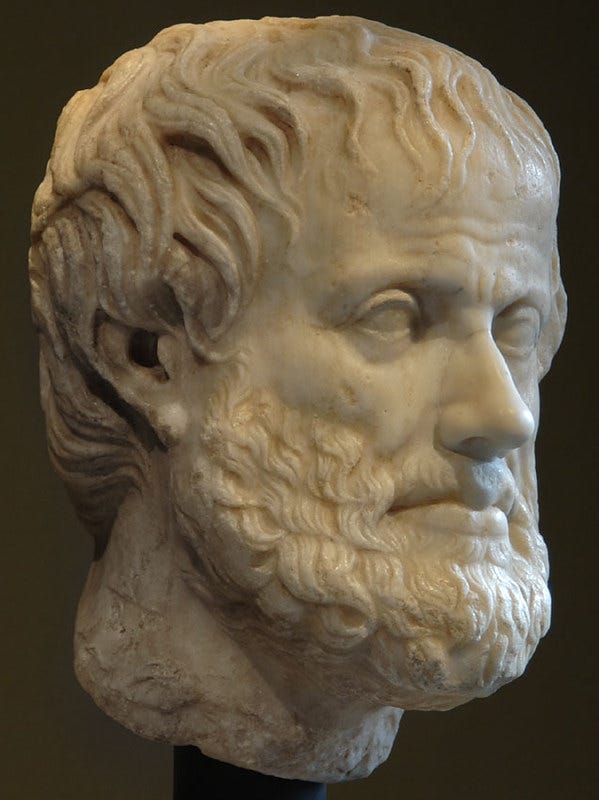

At least one famous figure, the philosopher Aristotle, endorsed abortion specifically as a method of fertility control. Writing in the 4th century B.C.E., he recommends in his Politics:

As regards whether to expose or nourish what is born, let the law be to nourish nothing that is defective but not to expose anything born, where the arrangement of customs forbids [more than a certain number of children], merely because of numbers. For there should be a limit to the amount of child-getting, but if some couple together and get offspring contrary to this, abortion should be procured before perception and life appear (what is and is not holy will be defined by perception and life). (Aristotle 1997, 1335b19)

While Aristotle specifically endorses abortion of pregnancy as a method of fertility control, this is only when abortion is induced before “perception and life” appear. This an early example of what might be called “threshold” attitudes toward abortion as a method of fertility control, which hold that killing fetuses or embryos as a method for family planning is acceptable before a certain point in their development, but killing them after this threshold is unacceptable. Such threshold attitudes include those that posit an inflection point such as “sentience,” “personhood,” etc., occurring in utero.

Description of Aristotle’s views on abortion as a method of fertility control is not to deny that there were a diversity of moral viewpoints on abortion in antiquity, much as the morality of abortion is a controversial subject in modern times. For instance, Soranus in his Gynecology relates how there was much disagreement about abortion in his day:

A contraceptive differs from an abortive, for the first does not let conception take place, while the latter destroys what has been conceived. Let us, therefore, call the one “abortive” (phthorion) and the other “contraceptive” (atokion). And an “expulsive” (ekbolion) some people say is synonymous with an abortive; others, however, say that there is a difference because an expulsive does not mean drugs but shaking and leaping, …. For this reason they say that Hippocrates, although prohibiting abortives, yet in his book “On the Nature of the Child” employs leaping with the heels to the buttocks for the sake of expulsion.

But a controversy has arisen. For one party banishes abortives, citing the testimony of Hippocrates who says: “I will give to no one an abortive”; moreover, because it is the specific task of medicine to guard and preserve what has been engendered by nature. The other party prescribes abortives, but with discrimination, that is, they do not prescribe them when a person wishes to destroy the embryo because of adultery or out of consideration for youthful beauty; but only to prevent subsequent danger in parturition if the uterus is small and not capable of accommodating the complete development, or if the uterus at its orifice has knobby swellings and fissures, or if some similar difficulty is involved. And they say the same about contraceptives as well, and we too agree with them. And since it is safer to prevent conception from taking place than to destroy the fetus, we shall now first discourse upon such prevention. (Soranus 1991, 62–63)

This passage is notable because there is no consideration as to whether it is morally wrong to kill embryos or fetuses per se. Even though Soranus understands the difference between contraception and abortion and relates the controversies around abortion, most of these disagreements are equally applicable to considerations about contraception.

Any discussion on whether it is wrong to kill embryos and fetuses like it is wrong to kill infants is absent from Soranus’ description because the idea that it was morally wrong to kill infants was not yet widely accepted. Indeed, Aristotle was ahead of his time in recommending that exposure not be used for fertility control, but only used to dispose of “defective” infants. This social context is important for understanding ancient attitudes toward abortion.

Legal Right to Infanticide in Greco-Roman Society

Throughout the ancient Greco-Roman era, infanticide was seen as a legal right. By the time of the Roman Empire, this attitude was embedded in the patria potestas, which stipulated the rights of a patriarch of a household, or pater familias, pertaining to his authority over the household. The patria potestas recognized that the pater familias wielded jus vitae ac necis (literally “the right of life and death”) over the children of the household, and could choose to raise, abandon, or outright kill whichever children he pleased. (Obladen 2016)

Sometimes decisions to not raise a child took the form of an overt act of killing, such as drowning a newborn in a bucket, but the practice of exposure, in which a neonate was abandoned in a public place, was also common. When exposure was done, the death of the child was likely, but there was always the possibility that someone else would take and raise the child. This is known to have sometimes occurred, since in the later imperial period the legal status of children exposed by one pater familias only to be raised by another became a political issue. (Grubbs and Parkin 2013)

Regardless of how unwanted children were disposed of, patria potestas and similar laws enshrined the legality of the practice. Proposing that children should be protected from arbitrary death would thus have been considered a strange opinion in antiquity. Therefore, as long as killing infants, either directly or indirectly through abandonment, were accepted practices in human society, it was unlikely that much consideration would be given to the morality of killing fetuses or embryos.

In addition to preventing moral reflection about abortion, infanticide and child abandonment may have been a more desirable alternative in antiquity, a time when abortion of pregnancy was considered risky for the mother. For instance, Plutarch relates a story about the legendary Spartan lawgiver Lycurgus:

Polydectes also died soon afterwards, and then, as was generally thought, the kingdom devolved upon Lycurgus; and until his brother’s wife was known to be with child, he was king. But as soon as he learned of this, he declared that the kingdom belonged to her offspring, if it should be male, and himself administered the government only as guardian. Now the guardians of fatherless kings are called “prodikoi” by the Lacedaemonians.

Presently, however, the woman made secret overtures to him, proposing to destroy her unborn babe on condition that he would marry her when he was a king of Sparta; and although he detested her character, he did not reject her proposition, but pretended to approve and accept it. He told her, however, that she need not use drugs to produce a miscarriage, thereby injuring her health and endangering her life, for he would see to it himself that as soon as her child was born it should be put out of the way.

In this manner he managed to bring the woman to her full time, and when he learned that she was in labour, he sent attendants and watchers for her delivery, with orders, if a girl should be born, to hand it over to the women, but if a boy, to bring it to him, no matter what he was doing. (Plutarch 1914, 210–11)

While stories about Lycurgus are semi-mythical and so do not tell us much about attitudes in the 9th century B.C.E. when he is supposed to have lived, this story does reflect on the sensibilities of Plutarch’s 1st or 2nd century C.E. audience, who would have been familiar with the attitude that infanticide or child abandonment were safer alternatives to abortion.

In the story, due to the rules of royal succession, Lycurgus is more interested in the child if it is a boy than if it is a girl. This highlights the fact that the ancients could use infanticide and child abandonment for more purposes than they could use abortion. For instance, a popular use of abortion today is sex-selective abortion, which occurs when parents screen the sex of a fetus and have it killed if it is an unwanted sex, typically female. This practice results in unbalanced sex ratios in many countries. (Chao et al. 2019)

Sex-selective abortion could not be done in antiquity, since a method for reliably determining the sex of a fetus was not available. This could be done with infanticide or child abandonment, however. For instance, the Oxyrhynchus Papyri contain a letter written in Egypt during the Roman era by a gentleman by the name of Hilarion to his wife Alis:

Hilarion to Alis his sister, hearty greetings, and to my lady Berous, and Apollonarion. Know that at present I am still in Alexandria. Don’t worry if they all come back, and I stay in Alexandria. I ask you, I urge you – care for the child, and if I soon get pay, I will send it up to you. If perhaps you give birth, then if it is male, let it be; if it is female, throw it out. You told Aphrodisias “Don’t forget me.” How can I forget you? So I ask you not to worry. (McKechnie 1999)

In addition to sex selection, infanticide and child abandonment could be used to dispose of children judged to be unhealthy or malformed, whereas those living in antiquity without modern fetal assessment technologies could not use abortion for a similar purpose, at least not effectively. Thus, Seneca, writing in the 1st century C.E., reports:

Unnatural progeny we destroy; we drown even children who at birth are weakly and abnormal. Yet it is not anger, but reason that separates the harmful from the sound. (Seneca 1928, 145)

Therefore, there must have been some in antiquity who saw infanticide and child abandonment as preferable to abortion of pregnancy since it was perceived to be safer and could be used for more purposes than just fertility control, such as sex selection and disposing of children deemed unhealthy.

Criminalization of Infanticide

The enshrinement in patria potestas of the legal right to dispose of unwanted children by infanticide and child abandonment was slowly eroded in the late Roman Empire until infanticide was finally outlawed in 374 C.E. during the overlapping reigns of emperors Valentinian, Valens, and Gratian. A few decades later, the Visigoths sacked Rome, and in time the (western) Roman Empire collapsed, but the Lex Visigothorum also outlawed infanticide. (Obladen 2016)

Despite the proscription of infanticide and child abandonment by some legal codes, the practices persisted. Pope Innocent III, reigning in the 13th century C.E., was so disturbed by the number of infant corpses being retrieved from the Tiber River in Rome by fishermen that he commissioned a foundling home to take in unwanted infants. (Grubbs and Parkin 2013)

The establishment of foundling homes was a widely used strategy in attempts to remedy infanticide, but to very limited success, as oftentimes foundling homes themselves had such high infant mortality rates that they were perceived to be not much better than exposure, and authorities struggled to institute policies to deal with infanticide well into the 19th century C.E. (Kilday 2013)

This inability of the authorities to eliminate infanticide in Europe throughout the late medieval and early modern periods despite the practice being outlawed was paralleled in other parts of the world. Curiously, ameliorating infanticide became a cause célèbre of European missionaries to China, leading to infanticide in East Asia being more well known for a time, despite infanticide being a social problem in Europe during the same time frame, as well. (Mungello 2008)

Christian Views on Sexuality

Much as understanding ancient Greco-Roman society’s views on abortion is complicated by the fact that the killing of infants was viewed as a legal right of patriarchs, understanding views on abortion after the spread of Christianity is complicated by the fact that contraception was (and in some cases, still is) viewed as a sin by prominent interpretations of Christianity.

Augustine, who lived during the 4th and 5th centuries C.E., is considered a saint in the Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church, and the Anglican Communion and was highly influential on early Christianity. Augustinian doctrine exalts chastity and considers any sexual intercourse except for the purpose of procreation to be sinful. This stems from a general attitude of avoiding excess or gluttony. In his treatise The Good of Marriage, Augustine writes:

Surely we must see that God gives us some goods which are to be sought for their own sake, such as wisdom, health, friendship; others, which are necessary for something else, such as learning, food, drink, sleep, marriage, sexual intercourse. Certain of these are necessary for the sake of wisdom, such as learning; others for the sake of health, such as food and drink and sleep; others for the sake of friendship, such as marriage or intercourse, for from this comes the propagation of the human race in which friendly association is a great good. So, whoever does not use these goods, which are necessary for something else, for the purpose for which they are given does well. As for him for whom they are not necessary, if he does not use them, he does better. (Augustine 1955, 21–22)

In Augustinian doctrine, while sexual intercourse done for pleasure instead of propagation of the human race is considered sinful, if this occurs between married couples, it is a lesser sin:

In marriage, intercourse for the purpose of generation has no fault attached to it, but for the purpose of satisfying concupiscence, provided with a spouse, because of the marriage fidelity, it is a venial sin; adultery or fornication, however, is a mortal sin. And so, continence from all intercourse is certainly better than marital intercourse itself which takes place for the sake of begetting children. (Augustine 1955, 17)

Indeed, according to Augustine, marriage itself makes sexual intercourse done for pleasure rather than procreation pardonable as long as it does not interfere with a couple’s pious activities:

… it is that sexual intercourse that comes about through incontinence, not for the sake of procreation and at the time with no thought of procreation, that [Paul the Apostle] grants as a pardon. Marriage does not force this type of intercourse to come about, but asks that it be pardoned, provided it is not so great as to encroach on the times that ought to be set aside for prayer … (Augustine 1955, 24)

Augustinian injunctions against sexual intercourse are thus intended to encourage piety. However, this doctrine also has the direct implication that any contraceptive methods are inimical to Christian piety, because their expressed purpose is to engage in sexual intercourse without procreation. Therefore, in Augustinian Christianity, contraception is itself a sin. This complicates interpretation of attitudes toward abortion of pregnancy.

Any Christian commentator who subscribes to Augustinian attitudes about sexuality will judge abortion to be wrong at least in the same way as contraception is judged to be wrong. This is a minor kind of wrong for which punishment is not necessary in Augustinian doctrine, so long as it occurs within marriage.

However, it is also possible that a Christian commentator would judge the killing of embryos and fetuses to be wrong in the way homicide is wrong, similarly to how the practices of infanticide and child abandonment were increasingly judged to be wrong during the same time period early Christianity was developing. This is a much more severe kind of wrong, as both Valentinian-era Roman law and the Lex Visogothorum prescribed capital punishment for those convicted of infanticide.

Furthermore, both kinds of judgement can be occurring in the commentary of Christians who subscribe to Aristotelian threshold attitudes toward abortion, which Augustine himself did.

If two men are fighting, and they strike a woman who is pregnant, and her child does not emerge deformed, he shall suffer a fine. As much as the woman’s husband shall specify, he shall give what is demanded. (Ex 21:22) It seems to be that this is said as having some meaning rather than as a scripture passage dealing with deeds of this sort. For, if its aim were that a pregnant woman not be struck and forced into a miscarriage, it would not posit two quarreling men, when it could be done by the one man who, when he was fighting with the woman herself, or, even if they were not fighting, nonetheless acted intentionally to harm another man’s posterity. But he did not intend the unformed child to be the object of murder, and surely he did not deem what is carried in the womb to be a human being. At this point it is customary to raise a question about the soul, namely, whether what has not been formed can even be understood to possess a soul, and therefore whether this would be murder, because it cannot be said to have been deprived of life if it did not yet have a soul, for [the passage] continues and says, But if it has been formed, he shall give a life for a life (Ex 21:23)….

Hence, if at the time that was indeed an unformed child, but still in some way possessed of an unformed soul (because the great question about the soul is not to be hurried along with the hastiness of an unconsidered opinion), the law was unwilling to make the case pertain to murder, because it cannot yet be called a living soul in that body which lacks sensation, if such [a soul] has not yet been formed in the flesh and [the flesh] has not yet been endowed with senses. (Augustine 2016, 14:130–31)

In this passage, Augustine recapitulates almost exactly the Aristotelian doctrine regarding prenatal life, such that there is a threshold in utero when offspring are “formed” after which killing an embryo or fetus is homicide, but before which it is not. All that has changed in Augustine’s view from Aristotle’s view is, in addition to concepts such as sensation and life, the concept of possession of a soul is added.

Quickening and Abortion in 19th Century Law

Trying to summarize views on abortion, contraception, and infanticide throughout the history of Christianity would likely require a book-length treatment and is beyond the scope of this article. However, a basically Aristotelian-Augustinian threshold attitude was popular enough throughout the centuries to become English common law and eventually be codified into laws of the United States.4

The threshold that developed in English common law for this purpose was called “quickening.” When a pregnant woman first felt movement from the embryo or fetus inside of her, she was said to be “quick with child.” This was taken to be the beginning of “perception and life” that Aristotle spoke about so many centuries before, and quickening became the inflection point after which the child was entitled legal protections.5

William Blackstone wrote in the seminal 18th century treatise Commentaries on the Laws of England:

Life is the immediate gift of God, a right inherent by nature in every individual; and it begins in contemplation of law as soon as an infant is able to stir in the mother’s womb. For if a woman is quick with child, and by a potion, or otherwise, killeth it in her womb; or if any one beat her, whereby the child dieth in her body, and she is delivered of a dead child; this, though not murder, was by the ancient law homicide or manslaughter. (Blackstone 1775, 129)

The United States of America after its creation inherited English common law regarding abortion of pregnancy because the several states lacked statute law on the matter. In 1821, Connecticut was the first of the states to enact its own statute regarding abortion of pregnancy, and quickening was reaffirmed as the Aristotelian-Augustinian threshold for protection of a child:

Every person who shall, willfully and maliciously, administer to, or cause to be administered to, or taken by, any person or persons, any deadly poison, or other noxious and destructive substance, with an intention him, her, or them, thereby to murder, or there to cause or procure miscarriage of any woman, then being quick with child, and shall be thereof duly convicted, shall suffer imprisonment, in newgate prison, during his natural life, or for such other term as the court having cognizance of the offence, shall determine. (Connecticut 1824, 96)

Other states followed with similar statutes, also using quickening as an Aristotelian-Augustinian threshold.

The 19th century, however, was also a time of rapid scientific advance. Karl Ernst von Baer published Ovi Mammalium et Hominis Genesi in 1827 and Über Entwickelungsgeschichte der Thiere in 1828. With greater awareness of the workings of mammalian developmental biology, concepts like quickening were increasingly seen as folk pseudo-knowledge. A select committee report in the Ohio state senate summed up this change in attitude:

The erroneous opinion has been entertained by the unthinking—and our law has favored the idea—that the life of the foetus commences only with quickening, and hence the conclusion that to destroy the embryo before that period is not child-murder, but only a venial offense. No opinion could be more erroneous. Quickening is generally purely mechanical. The uterus, in consequence of its enlargement, rises from the cavity of the pelvis to that of the abdomen. Hence the sensation of motion.

The period of quickening is uncertain. Some women are not conscious of foetal motion during the whole period of pregnancy. Others are sensible of it much before the usual time. Physiological researches have demonstrated that it exists in the early stages of utero-gestation, but it is too feeble to be perceived by the mother. The law now is settled, and it has averred, in most pithy and expressive language, that “quick with child is having conceived;” but our statutes have made an unnatural and unscientific distinction. Let it be proclaimed to the world, and let it be impressed upon the conscience of every woman in the land, “that the willful killing of a human being, at any stage of its existence, is murder.” (Ohio 1867, 234)

The Ohio senate subcommittee’s use of the term “venial” in this context is a conspicuous allusion to Aristotelian-Augustinian doctrine.

Throughout the 18th century, legislatures of the several states of the United States moved away from using quickening as an Aristotelian-Augustinian threshold. Some passed new statutes that simply removed any reference to quickening from the old statute. Maine is notable for having explicitly rejected quickening as a threshold in the text of its new statute:

Every person, who shall administer to any woman pregnant with child, whether such child be quick or not, any medicine, drug or substance whatever, or shall use or employ any instrument or other means whatever, with intent to destroy such child, and shall thereby destroy such child before its birth, unless the same shall have been done as necessary to preserve the life of the mother, shall be punished by imprisonment in the state prison, not more than five years, or by fine, not exceeding one thousand dollars, and imprisonment in the county jail, not more than one year. (Maine 1840, 686)

Comstock Laws

While the Aristotelian-Augustinian threshold of quickening was removed from criminal abortion statutes in the 19th century, Augustinian views on sexuality led to statutes prohibiting dissemination of information pertaining to contraception and abortion in what would be called the “Comstock laws.” A United States Criminal Code bill entitled “An Act for the Suppression of Trade in, and Circulation of, obscene Literature and Articles of immoral Use” passed in 1873 reads:

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That whoever, within the District of Columbia or any of the Territories of the United States, or other place within the exclusive jurisdiction of the United States, … shall have in his possession, for any such purpose or purposes, any obscene book, pamphlet, paper, writing, advertisement, circular, print, picture, drawing or other representation, figure, or image on or of paper or other material, or any cast, instrument, or other article of an immoral nature, or any drug or medicine, or any article whatever, for the prevention of conception, or for causing unlawful abortion, … shall be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor, and, on conviction thereof in any court of the United States having criminal jurisdiction in the District of Columbia, or in any Territory or place within the exclusive jurisdiction of the United States, where such misdemeanor shall have been committed ; and on conviction thereof, he shall be imprisoned at hard labor in the penitentiary for not less than six months nor more than five years for each offense, or fined not less than one hundred dollars nor more than two thousand dollars, with costs of court. (Sanger 1873, 17:598–99)

Margaret Sanger lobbied to remove the Comstock laws’ prohibitions on contraception with the goal of ending abortion as a method of fertility control, a subject given a full treatment in its own article. Much as the removal of quickening from criminal abortion laws in the 19th century was a removal of Aristotelian-Augustinian ideas about prenatal life, the removal of prohibitions on contraception in the 20th century was the removal of Augustinian ideas about sexuality from United States obscenity law.

Abortion is Common

In the United States

Before 1973

Similarly to how laws criminalizing infanticide did not bring infanticide to an end, abortion of pregnancy persisted into the 20th century in the United States as a common occurrence despite it being prohibited. Because it was an underground activity, estimates of how frequently embryos or fetuses were intentionally killed varied wildly. Margaret Sanger, speaking in 1918, relates the opinions of the experts she consulted:

In the very nature of the case, it is impossible to get accurate figures upon the number of abortions performed annually in the United States. It is often said, however, that one in five pregnancies end in abortion. One estimate is that 150,000 occur in the United States each year and that 25,000 women die of the effects of such operations in every twelve months. Dr. William J. Robinson asserts that there are 1,000,000 abortions every year in this country and adds that the estimate is conservative. He quotes Justice John Proctor Clark as saying that there are at least 100,000 in the same length of time in New York City alone.

Dr. Max Hirsch, a famous authority quotes an opinion that there are 2,000,000 abortions in the United States every year!

“I believe” declares Dr. Hirsch, “that I may say without exaggeration that absolutely spontaneous or unprovoked abortions are extremely rare, that a vast majority—I should estimate it at 80 per cent—have a criminal origin.”

“Our examinations have informed us that the largest number of abortions are performed on married women. This fact brings us to the conclusion that contraceptive measures among the upper classes and the practice of abortion among the lower class, are the real means employed to regulate the number of offspring.” (Sanger 1918)

Today

There are more accurate counts of the number of abortions occurring today than in Margaret Sanger’s time, though estimates still suffer from some issues in accuracy.

The Centers for Disease Control publishes annual Abortion Surveillance reports that collect data provided by the several states of the United States. (Kortsmit 2022) However, the Abortion Surveillance reports are known to be incomplete because of variation in reporting by the states. Most notably, some states, including very populous ones like California, do not report to the Centers for Disease Control at all. Therefore, the Abortion Surveillance reports are underestimates.

The National Survey of Family Growth administered by the National Center for Health Statistics is a periodic survey of nationally representative samples of persons living in the United States pertaining to reproductive behavior. The National Survey of Family Growth is quite accurate in estimating some pregnancy outcomes such as the number of live births, as confirmed by vital records statistics. However, abortions are under-reported on the National Survey of Family Growth such that its official documentation advises against using the survey results for analysis of abortion. (“Appendix 2: Topic-Specific Notes for 2017-2019, NSFG User’s Guide” 2021)

The most accurate counts of abortions induced in the United States come not from government official statistics, therefore, but from the Guttmacher Institute, an abortion advocacy think tank. The Guttmacher Institute periodically conducts its Abortion Provider Census, which is a census in the sense that every abortion provider in the United States is asked for a count of abortions induced. The statistics reported from the Abortion Provider Census include some estimation, however, because some abortion providers do not reply to the Abortion Provider Census, and so the Guttmacher Institute must estimate counts for these nonrespondents. (Jones, Kirstein, and Philbin 2022)

Nonetheless, estimates of abortions induced in the United States from the Abortion Provider Census are consistently greater than those from either the Abortion Surveillance Reports or the National Survey of Family Growth and are likely the most accurate counts of abortions induced in the United States.

According to the Abortion Provider Census, the number of abortions induced in the United States peaked in the 1980s around 1,600,000 per year and declined to just under 900,000 per year in the late 2010s. (Estimates from the 1970s may have been underestimates due to under-coverage, given the legalization of abortion in that decade.)

Worldwide

There have been several attempts to estimate the number of abortions induced worldwide by aggregating estimates for each country in the world. These worldwide estimates are estimates from models that themselves are based on estimates from national surveys, each of which might have issues such as discussed above for the case of the United States. They should be interpreted with caution, but can at least give a rough estimate. The latest such model estimates approximately 73.3 million abortions per year worldwide. (Bearak et al. 2020)

Conclusion

There has been a trend toward protecting children from being arbitrarily killed at earlier and earlier points in their development. Western civilization began with no such protection, and instead enforced the legal right of patriarchs to choose which children to raise and which to kill as enshrined in laws such as patria potestas. In the late Roman Empire this became increasingly a controversial issue, until infanticide was outlawed in 374 C.E. This created the first protection of children from arbitrary killing, and established the point of protection at birth.

Later, as Aristotelian-Augustinian doctrine regarding prenatal life was codified into law in the medieval and early modern periods, this protection was extended even earlier in child development to a threshold that would come to be known in English common law as “quickening.” Eventually in the 19th century, quickening was seen as pre-scientific folk belief, and with the removal of quickening criteria from criminal abortion law, the point at which children were protected from being killed arbitrarily was effectively moved all the way to their conception.

While there has been a trend toward protecting children earlier and earlier in their development, these protections have failed spectacularly. For more than a thousand years after infanticide was made illegal and as late as the 19th century, authorities struggled with what to do about mass infanticide occurring in their jurisdictions. Even though 19th century legal changes effectively criminalized abortion at any point during a pregnancy, abortion continued into the 20th century.

Approval of abortion of pregnancy as a method of fertility control is conservative because it is disposed to maintain existing conditions. Abortion has been advocated as a method of fertility control for more than thousand years, since at least the Greek classical period. Abortion is extremely common today; there are tens of millions of abortions every year. Abortion is the status quo.

Furthermore, approval of abortion goes against a trend of protecting children earlier and earlier in their development that has slowly progressed for the past two millennia of Western civilization. If advocacy of abortion limits itself to advocating abortion before a threshold in utero, then such advocacy is a return to pre-19th century thinking about prenatal life. If advocacy of abortion includes advocacy of abortion all the way up until birth, then such advocacy is a return to 4th century C.E. thinking.

The conservatism of approval of abortion has broad ramifications for those who are opposed to killing unborn children as a method of fertility control. Conservative – in the definition used here – approaches are the wrong approaches. History has nothing but thousands of years of infanticide, child abandonment, and abortion to offer. There has never been a time of reproductive responsibility through nonviolent fertility control. There is no golden era to return to.

Opposition to abortion is new, tenuous, and radical. The absence of a past to emulate forces those opposed to abortion to aspire to a future that has not yet been realized. Advocates of abortion have an easy task; they need only to perpetuate the status quo, perhaps amend a few laws here and there to their liking, but generally keep the human condition as it is. Opponents of abortion, however, must drastically reshape human civilization.

Such changes can be imperceptibly slow, and oftentimes they are generational. They do, however, happen. Who today would advocate for the right to infanticide that patria potestas once enshrined?

References

“Appendix 2: Topic-Specific Notes for 2017-2019, NSFG User’s Guide.” 2021. National Center for Health Statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nsfg/NSFG-2017-2019-UG-App2-TopicSpecificNotes-508.pdf.

Aristotle. 1997. Politics of Aristotle. Translated by Peter L. Phillips Simpson. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press.

Augustine. 1955. Treatises on Marriage and Other Subjects. Baltimore: Catholic University of America Press.

———. 2016. Writings on the Old Testament. Edited by Boniface Ramsey. Vol. 14. The Works of Saint Augustine: A Translation for the 21st Century. Hyde Park: New City Press.

Bearak, Jonathan, Anna Popinchalk, Bela Ganatra, Ann-Beth Moller, Özge Tunçalp, Cynthia Beavin, Lorraine Kwok, and Leontine Alkema. 2020. “Unintended Pregnancy and Abortion by Income, Region, and the Legal Status of Abortion: Estimates from a Comprehensive Model for 1990–2019.” The Lancet Global Health 8 (9): e1152–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30315-6.

Blackstone, William. 1775. Commentaries on the Laws of England. Dublin: The Company of Booksellers. //catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/010428707.

Chao, Fengqing, Patrick Gerland, Alex R. Cook, and Leontine Alkema. 2019. “Systematic Assessment of the Sex Ratio at Birth for All Countries and Estimation of National Imbalances and Regional Reference Levels.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116 (19): 9303–11. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1812593116.

Connecticut. 1824. The Public Statute Laws of the State of Connecticut: As Revised and Enacted by the General Assembly, in May, 1821. Hartford. //catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/010448275.

“Conservative.” 2023. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/conservative.

Dioscorides. 2000. De Materia Medica. Translated by Tess Anne Osbaldeston. Ibidis Press.

Grubbs, Judith Evans, and T Parkin. 2013. “Infant Exposure and Infanticide.” The Oxford Handbook of Childhood and Education in the Classical World, 83–97.

Gump, Daniel. 2023. Criminal Abortion Laws Across Before the Fourteenth Amendment. 2nd edition. https://www.patreon.com/danielgump/.

Hippocrates. 2012. Nature of the Child. Translated by Paul Potter. Loeb Classical Library 520. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Jones, Rachel K., Marielle Kirstein, and Jesse Philbin. 2022. “Abortion Incidence and Service Availability in the United States, 2020.” Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health 54 (4): 128–41. https://doi.org/10.1363/psrh.12215.

Kilday, A. 2013. A History of Infanticide in Britain, c. 1600 to the Present. Springer.

Kortsmit, Katherine. 2022. “Abortion Surveillance — United States, 2020.” MMWR. Surveillance Summaries 71. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss7110a1.

Maddow-Zimet, Isaac, Kathryn Kost, and Sean Finn. 2022. “Pregnancies, Births and Abortions in the United States: National and State Trends by Age.” Open Science Framework. https://osf.io/kthnf/.

Maine. 1840. “The Revised Statues of the State of Maine.” http://lldc.mainelegislature.org/Open/RS/RS1840/RS1840_c160.pdf.

McKechnie, Paul. 1999. “An Errant Husband and a Rare Idiom (P. Oxy. 744).” Zeitschrift Für Papyrologie Und Epigraphik, 157–61.

Mungello, David E. 2008. Drowning Girls in China: Female Infanticide in China Since 1650. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Obladen, Michael. 2016. “From Right to Sin: Laws on Infanticide in Antiquity.” Neonatology 109 (1): 56–61. https://doi.org/10.1159/000440875.

Ohio. 1867. Journal of the Senate of the State of Ohio. Zanesville. //catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/012323116.

Plutarch. 1914. Lives, Lycurgus. Translated by Bernadotte Perrin. Loeb Classical Library 46. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Sanger, George P., ed. 1873. Statutes at Large, 42nd Congress, 3rd Session. Vol. 17. A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774 - 1875. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company. https://memory.loc.gov/ammem/amlaw/lwsllink.html.

Sanger, Margaret. 1918. “Birth Control or Abortion?” Birth Control Review, December, 3–4.

Seneca. 1928. Moral Essays. Translated by JW Basore. Loeb Classical Library 310. London.

Soranus. 1991. Gynecology. Translated by Owsei Temkin. Softshell Books ed. ACLS Humanities E-Book. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Unless otherwise noted, in this article the word “abortion” is used to mean abortion of pregnancy.

Technically, the word “abortion” is a generic term. Any process that is aborted before it comes to completion can, in theory, be labeled “abortion.” However, because of its association with abortion of pregnancy and the emotional weight of such occurrence, the word “abortion” is usually used to mean abortion of pregnancy.

Furthermore, even if we just consider “abortion” to mean abortion of pregnancy, there is ambiguity because in the medical literature the word “abortion” is used to mean two different things: spontaneous abortion, which is commonly called “miscarriage” in the vernacular, occurs when a pregnancy terminates without anyone’s intervention; abortion occurs when a pregnancy is terminated on purpose. When “abortion” is used in the vernacular it is commonly used to mean abortion.

This ambiguity can lead to misinterpretation. For instance, if a study were to report on abortions in a given population, it could be including both spontaneous and abortions if it were using the medical literature definition, but it could be excluding what are commonly called “miscarriages” if it were using the common definition.

This article focuses on European history and Greco-Roman history in particular. This is not because social phenomena occurring in a European context deserve primacy of consideration, but because there is an abundance of scholarship available to someone doing research in the English language regarding European history, whereas studying other social contexts is more challenging and beyond the scope of this article. This article seeks to establish that induced abortion of pregnancy as a method of fertility control is a very old practice, and Greco-Roman scholarship provides a well-documented example.

The 66 abortifacients described in De Materia Medica are kardamomon (p. 6), kinamomon (pp. 18-19), balsamon (pp. 23-24), aspalathos (pp. 24-25), sampsuchinon (pp. 55-56), bdellion (pp. 82-83), kedros mikra (pp. 102-103), daphne (p. 106), leuke (p. 109), katoros orchis (p. 193), oisupon (p. 212), pitua (p. 213), apopatos (pp. 222-223), erebinthos (p. 244), thermos emeros (p. 255), sion to en odasin (p. 280), kardamon (p. 312), thlaspi (p. 315), piper (pp. 316-319), strouthion (p. 323), kuklaminos (pp. 323-324), drakontion meca (pp. 327-328), drakontion mikron (pp. 328-331), kissos (pp. 351-352), gentiane (p. 367), aristolochia klematitis (pp. 368-371), kentaurion makron (p. 372), kentaurion mikron (p. 375), glechon (p. 404), elelisphakon (p. 408), kalaminthe (p. 412), thmos (p. 415), bakcharis (pp. 420-423), peganon to kepaion (pp. 423-427), panakes herakleion (pp. 428-431), seseli massaleotikon (p. 436), anethon (p. 443), smurnion (p. 455), daukos (p. 460), sagapenon (p. 479), chalbane (pp. 480-483), ammoniakon (pp. 483-484), klinopodion (p. 492), chamaidrus (p. 496), artemisia monoklonos (pp. 513-514), konuza (pp. 517-518), leukoion (p. 519), onosma (pp. 523-524), anthemis (pp. 527-528), eruthrodanon (p. 532), anaguris (p. 535), anchousa (p. 567), mandragoras (p. 624), elleboros (pp. 696-699), elleboros melas (pp. 700-703), elaterion (pp. 707-708), skammonia (pp. 726-727), thumelaia (p. 728), kolokunthis (p. 731), ampelos leuke (pp. 733-734), thelupteris (p. 736), eliotropion mega (p. 739), oinos phthorios enibruon (p. 778), oinos elleborites (pp. 779-780), stupteria (pp. 806-807), theion (p. 807).

This section’s discussion of the history of United States laws pertaining to abortion in the 19th century owes considerably to Criminal Abortion Laws Across Before the Fourteenth Amendment (Gump 2023).

Incidentally, this is also the origin of phrase “the quick and the dead” in traditional versions of the Apostles’ Creed in which Jesus “sitteth at the right hand of God the Father Almighty; from thence he shall come to judge the quick and the dead.”